<--

Brian Brooks, Maura Conley, Heather Lewis, James Lipovac, and Micki Spiller

“A Sense of Belonging”: Alternative Assessment in the First Year

Brian Brooks, Maura Conley, Heather Lewis, James Lipovac, and Micki Spiller

This article describes emergent research findings from an ongoing qualitative research study of a cross-departmental alternative assessment pilot at Pratt, with a specific focus on Pratt’s undergraduate Foundation program. The quantitative research component of the pilot will be discussed in a future article. While the pilot also included faculty in other departments (Humanities and Media Studies, History of Art and Design, Graduate Communication Design) this article focuses on the qualitative research conducted by Foundation faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC). Preliminary findings suggest that learning in the gradeless studio is grounded in instructional practices that promote a “sense of belonging” for both students and professors, as well as a place in which self-assessment, reflection, and feedback are valued and practiced.

Alternative Assessment (Gradeless) Pilot

The pilot grew in scale over three years, informed by James Lipovac’s research in 2019 when he was awarded a Faculty Fellowship in Foundation from Pratt Institute’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) to study methods of un-grading in his first-year studio art course. By the time he started his research, COVID was everywhere and the move to remote learning had already begun. That spring, virtually all colleges in America switched temporarily to pass/fail. This seismic shift was quickly followed by the cultural awakening precipitated by the murder of George Floyd. Both events turned many academic traditions on their heads across the country.

James’s work on ungraded assessment became unexpectedly relevant and exciting to colleagues at Pratt, generating a Gradeless Assessment Pilot beginning in academic year 2020–21 with three professors and eighteen students in the Foundation department, expanding to twenty-five professors and 132 students in academic year 2021–22, and to a cross-institutional pilot in 2022–23 involving eight professors and thirty students in History of Art & Design, Art & Design Education, and Humanities and Media Studies, and six classes with seventy students in Graduate Communication Design. Though students knew they were in a gradeless pilot program, students also knew that, ultimately, they would receive a grade on their transcript. A total of more than 200 students taking courses across seven disciplines within three departments participated. Despite the fact that this work has yet to be officially institutionalized, faculty have nonetheless started to reshape teaching and learning at Pratt as a result.

Over the past five years, faculty across Pratt engaged in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in diverse areas such as the transfer of learning, learning as narrative, learning in the first year, and critique as a signature pedagogy in art and design education. Faculty research on critique (Crit the Crit Faculty Learning Community, 2016–2019) explored studio-based critique methodologies and typologies used at Pratt in art and design disciplines. This led to a subsequent publication, which theorized critique and power (Martin-Thomsen, et al., 2021) and institute-wide explorations of gradeless assessment and non-inclusive forms of critique. Through the CTL’s Faculty Fellowship (2021) and Gradeless Assessment Deep Dive Community (2022), faculty researched alternative approaches to assessment. A description and examples of some of the work are available on the CTL website.

This article is based on recent action research conducted by faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC) in their courses and programs over the 2022–23 academic year. Faculty reviewed literature in the field on feedback and alternative assessment (Winston & Boud, 2022; O’Donavan, et al. 2021; Winstone, et al., 2017; Molloy, Boud, & Henderson, 2021), posted their teaching artifacts on a shared Milanote board, shared their research at monthly FLC meetings, and analyzed their teaching through narrative inquiry. While this article constitutes a snapshot of ongoing research, the emergent findings and a review of the existing literature in the field of alternative assessment and feedback suggest that Pratt’s pilot work in this area offers a strong contribution to the field given its scope as well as depth. It also suggests that the small, significant networks of SoTL practitioners in the area of alternative assessment provide a foundation on which to expand alternative assessment at Pratt (Verwood & Pool, 2016).

The pilot grew in scale over three years, informed by James Lipovac’s research in 2019 when he was awarded a Faculty Fellowship in Foundation from Pratt Institute’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) to study methods of un-grading in his first-year studio art course. By the time he started his research, COVID was everywhere and the move to remote learning had already begun. That spring, virtually all colleges in America switched temporarily to pass/fail. This seismic shift was quickly followed by the cultural awakening precipitated by the murder of George Floyd. Both events turned many academic traditions on their heads across the country.

James’s work on ungraded assessment became unexpectedly relevant and exciting to colleagues at Pratt, generating a Gradeless Assessment Pilot beginning in academic year 2020–21 with three professors and eighteen students in the Foundation department, expanding to twenty-five professors and 132 students in academic year 2021–22, and to a cross-institutional pilot in 2022–23 involving eight professors and thirty students in History of Art & Design, Art & Design Education, and Humanities and Media Studies, and six classes with seventy students in Graduate Communication Design. Though students knew they were in a gradeless pilot program, students also knew that, ultimately, they would receive a grade on their transcript. A total of more than 200 students taking courses across seven disciplines within three departments participated. Despite the fact that this work has yet to be officially institutionalized, faculty have nonetheless started to reshape teaching and learning at Pratt as a result.

Over the past five years, faculty across Pratt engaged in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in diverse areas such as the transfer of learning, learning as narrative, learning in the first year, and critique as a signature pedagogy in art and design education. Faculty research on critique (Crit the Crit Faculty Learning Community, 2016–2019) explored studio-based critique methodologies and typologies used at Pratt in art and design disciplines. This led to a subsequent publication, which theorized critique and power (Martin-Thomsen, et al., 2021) and institute-wide explorations of gradeless assessment and non-inclusive forms of critique. Through the CTL’s Faculty Fellowship (2021) and Gradeless Assessment Deep Dive Community (2022), faculty researched alternative approaches to assessment. A description and examples of some of the work are available on the CTL website.

This article is based on recent action research conducted by faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC) in their courses and programs over the 2022–23 academic year. Faculty reviewed literature in the field on feedback and alternative assessment (Winston & Boud, 2022; O’Donavan, et al. 2021; Winstone, et al., 2017; Molloy, Boud, & Henderson, 2021), posted their teaching artifacts on a shared Milanote board, shared their research at monthly FLC meetings, and analyzed their teaching through narrative inquiry. While this article constitutes a snapshot of ongoing research, the emergent findings and a review of the existing literature in the field of alternative assessment and feedback suggest that Pratt’s pilot work in this area offers a strong contribution to the field given its scope as well as depth. It also suggests that the small, significant networks of SoTL practitioners in the area of alternative assessment provide a foundation on which to expand alternative assessment at Pratt (Verwood & Pool, 2016).

Internal and External Contexts

Pratt’s Gradeless Assessment Pilot is part of a broader focus on equity in assessment in higher education across the country (Montenegro & Jankowski, 2020; McArthur, 2019). The more recent effects of equity reforms in higher education, as well as decolonizing the curriculum in higher education, sparked a re-examination of assessment practices not only at Pratt, but also nationally and internationally (Bhumbra, 2018).

Though Pratt's transition to pass/fail during the first COVID semester felt like a quick pivot necessitated by the pandemic, the Foundation department adapted gradeless practices with the hopes of building something intentional, more sustainable, and well-scaffolded for professors and students alike. To that end, Lipovac (personal communication, 2022) explains how the gradeless approach has shifted in Foundation over the years:

Pratt’s Gradeless Assessment Pilot is part of a broader focus on equity in assessment in higher education across the country (Montenegro & Jankowski, 2020; McArthur, 2019). The more recent effects of equity reforms in higher education, as well as decolonizing the curriculum in higher education, sparked a re-examination of assessment practices not only at Pratt, but also nationally and internationally (Bhumbra, 2018).

Though Pratt's transition to pass/fail during the first COVID semester felt like a quick pivot necessitated by the pandemic, the Foundation department adapted gradeless practices with the hopes of building something intentional, more sustainable, and well-scaffolded for professors and students alike. To that end, Lipovac (personal communication, 2022) explains how the gradeless approach has shifted in Foundation over the years:

Initially, focus was on faculty assessments of the students. As the pilot evolved, that has shifted nearly completely to student assessments supported by faculty and peer feedback. Faculty are taught, through a series of workshops, to forgo not just grades, but also traditional summative assessments, in favor of well-timed feedback sessions designed to help the students self-reflect and take the lead in their own learning.

The following infographic provides a snapshot of the relationship between the Gradeless Assessment Pilot and Foundation Program Learning Outcomes.

Figure 1

Foundation Department Learning Outcomes Aligned With Gradeless Assessment Pilot

This article focuses on qualitative research by six Foundation faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Pilot.

Faculty Learning Community Participants and Process

In the academic year 2022–23, the Foundation department supported a Faculty Learning Community consisting of eleven faculty members from four departments and the CTL (see list below). All members of the FLC studied their courses over two semesters. FLC members agreed to an overarching FLC research question: How has (gradeless) assessment changed how we teach? Each individual faculty member then developed a related research question specific to their course. The FLC discussed a shared reading about feedback and reflection (Winston & Boud, 2022), developed a research plan, and analyzed their teaching based on the evidence they collected through narrative inquiry (Leiblich et al., 1998). Everyone shared their work on Milanote and in monthly FLC meetings that featured two to three faculty members’ emergent findings each month.

The faculty research boards in Figure 2 illustrate the work of six FLC faculty members from the Foundation department. Each faculty member introduced student reflection and/or student self-assessment in their classes through such practices and processes as digital journals, ongoing reflective benchmarking processes, process books that include self-assessment, faculty and peer feedback, and structured, cumulative reflection.

Figure 2

FLC Milanote Board

The following are brief summaries describing an instructional intervention, research question, and subquestions in one of the gradeless courses. FLC Milanote Board

Kyle Williams: Student Digital Open Journal

Course: Time and Movement

Figure 3

Student Digital Open Journal

Student Digital Open Journal

Instructional Intervention Description

Using the Milanote digital platform, each student creates a board to be their unique journal.

- The journal is meant for students to reflect and process information without the context of a public forum. However, it is not private. It is also meant to be a place where the student and I can share information.

- Each class, the students answer a question or reflect on a topic I give them in their journal. When questions are analytical, I begin with a low-stakes free-writing prompt.

- Journal questions/topics ask students to reflect on the work that they and their peers are making, including reflecting on class critiques and works in progress. This includes asking students to copy and paste the work of their peers and their own work into the Milanote board to discuss and assess it.

- Talking about peers’ work is just as important as talking about their own work.

- There is no prescribed format for this—it is not something that needs to look good.

- I respond to posts within the journal.

Overall, the open journal should be a place where students are practicing the skills of describing how and why a project works as well as a place where I can respond to their writing and their work with feedback. It should be a place where I can model how to evaluate projects and how to connect ideas we cover in class to the work they are making.

Research Question and Subquestions

How can a shared digital journal be an effective platform for faculty feedback and students' self-regulated learning?

- Is it possible to find a balance of a semi-private space to write that is also a shared space between the teacher and student, and that can be secured from other students reading it? Can this "semi-private" status be presented as a positive? The idea of "learning in public."

- Logistically, is it possible for the teacher to make the time commitment to actively engage with each student on the journal effectively?

- How can I make written self-assessments not feel like busy-work?

- Can this reflective journal effectively be used to model, through feedback, how to look at / think about / speak about work and how to connect making to our class concepts?

Andy Lenaghan: Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Course: Visualization and Representation

Figure 4

Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Instructional Intervention Description

Self-assessment as a goal of the course is introduced and sustained throughout the course with student writing exercises that benchmark student progress. This intervention provided knowledge about the student’s verbal understanding of the course outcomes from the beginning to the end of the course. Through the ongoing reflective benchmarking process, students participated in self-assessment in writing and image selection according to attributes.

Research Question

Can students self-assess and demonstrate their understanding of course outcomes verbally and in their work without a grade as motivation?

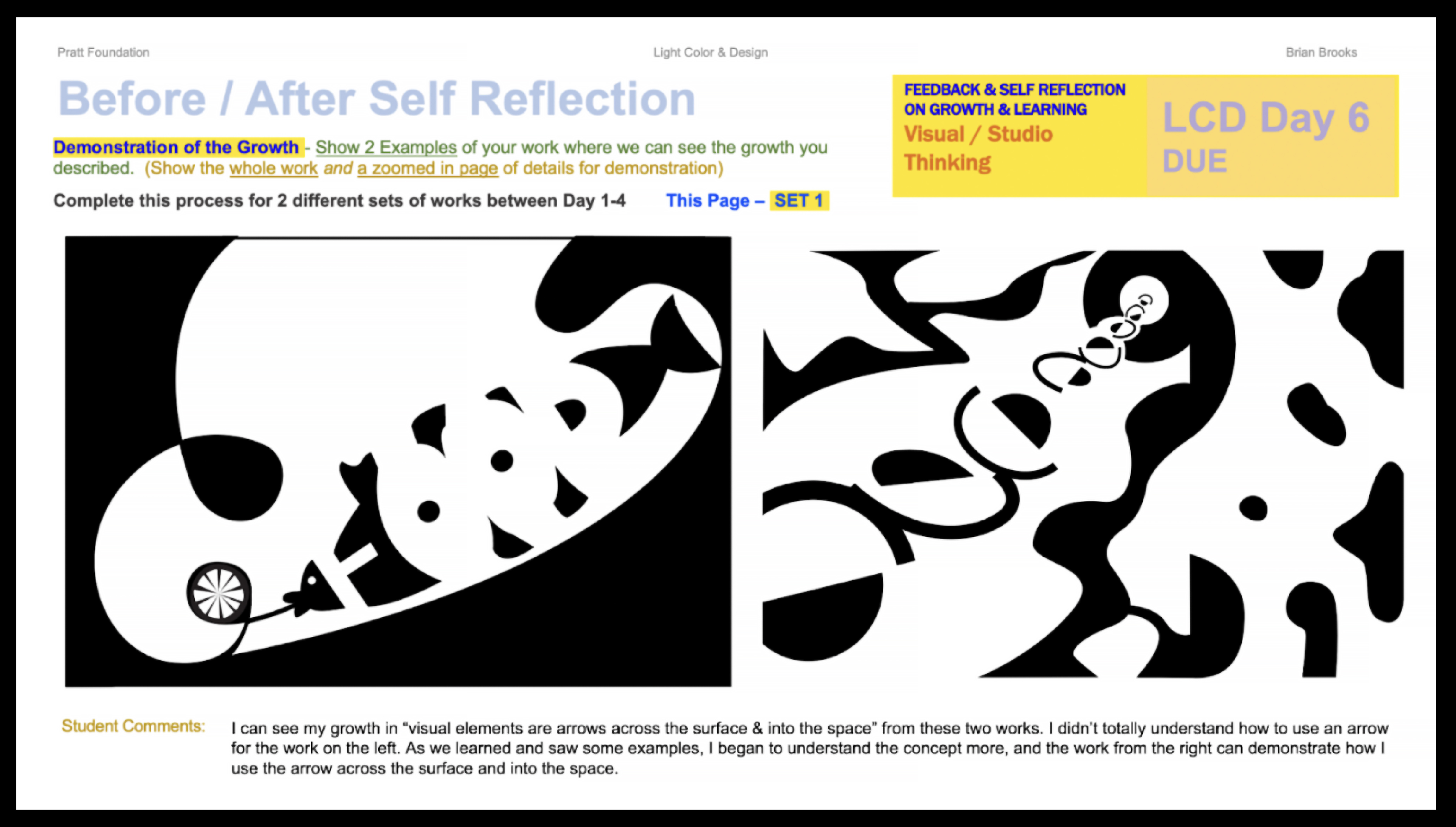

Brian Brooks: Student Process Books (for Reflection and Feedback)

Course: Light, Color, and Design

Figure 5

Process Book

![]()

Process Book

Instructional Intervention Description

In this course, the students document their semester-long work in an Individual Process Book using a Google Slide template created for depositing all works in progress and completed classwork (CW) and homework (HW) assignments. I emphasized work in progress because the overall theme of the course, as far as learning goes, is growth… in a student’s learning process. The teacher watches growth and helps students look for and recognize it. This is the feedback conversation about learning that far outweighs the value of grades. A student grasping their growth and development seems to anchor their course learning on concrete products and processes used in class, which I suspect helps them identify their growth and test it in the future.

Research Question and Subquestions

How can we assess students without grades?

- How can I assess students without grades?

- What have grades helped students learn, and what is the best alternative to using grades?

- What is essential to a student’s learning process?

- What are the least “invasive” ways to create self-reflection in students that generates conversations and self-awareness and that helps them:

- See strengths in their processes

- More accurately pin-point where “improvement” can happen in “grasping concrete learning objectives & concepts” in the course

- Develop multiple areas of practice (where concepts have multiple uses, applications, and paths for transfer to develop learning course concepts)

- Reinforce their strengths and aim more closely and specifically at where they need to improve

- Make the self-reflective process more visual and concrete

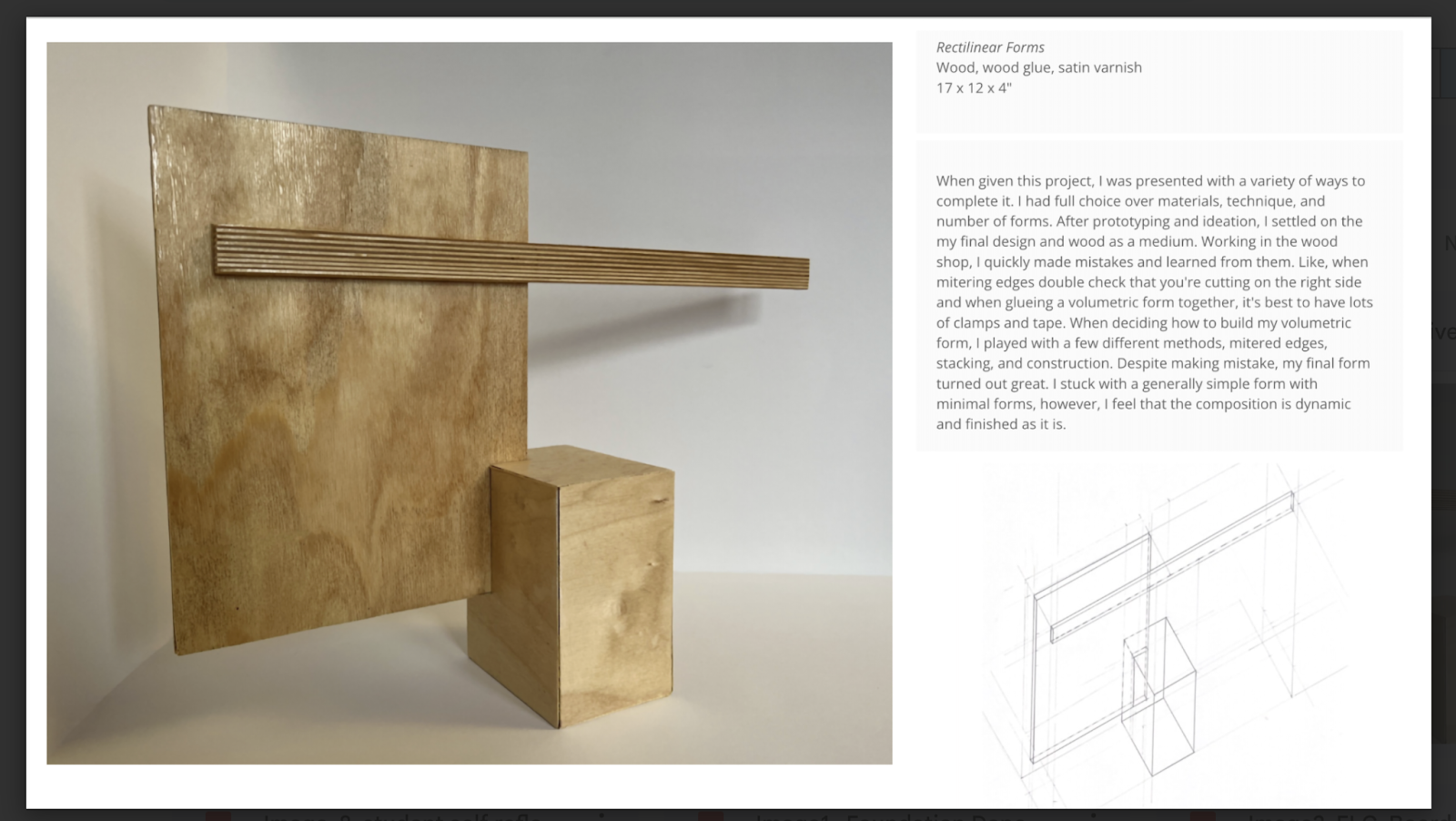

Micki Spiller: Reflective Writing

Course: Space, Form, and Process

Figure 6

Reflective Writing

Reflective Writing

Instructional Intervention Description

This is a mandatory one-semester first-year class focusing on fundamental principles of 3D design and techniques of haptic building. The instructor and peers give feedback and assess with the use of rubrics throughout the course. The students and instructor discuss the student’s final grades through self-reflection (see Figure 6).

Table 1

Stages of Self-Reflection and Feedback

Stages of Self-Reflection and Feedback

Research Question

In a first-year course, what replaces a student's primary motivation tool when grades are no longer used?

- Reflection helps students to think about the learning outcomes and how they have met them two times a semester.

- Students are more involved in their own learning.

- Focus is on assessment of individual ability to progress rather than of prior knowledge.

James Lipovac: Structured Reflection and Feedback on Self-Regulation

Course: Visualization and Representation

Figure 7

Screenshot of Student Self-Reflection About Self-Regulation

Screenshot of Student Self-Reflection About Self-Regulation

Instructional Intervention Description

James helped students monitor and assess their progress with regards to:

- risk taking

- problem solving

- time management

- community interaction

- communication skills

- technical proficiency

A focus has been placed in the course on moving up the timing of faculty feedback to happen earlier in the creative process in an effort to provide students with constructive support with enough time to act on it. By moving up the feedback, students will be empowered to experiment with peer, self, and faculty feedback.

Research Question

How can faculty and peer feedback affect self-regulation?

Emergent Themes

Based on faculty narrative inquiry, the following themes emerged across individual faculty research: building community, the value and challenge of reflection in the curriculum, changing faculty teaching practices, and encouraging student ownership of their learning and assessment fluency. The following sections provide a brief description of two of the themes illustrated with quotes from faculty summarizing their findings in response to their research questions. Further analysis, beyond the scope of this article, is vital to fully understand how gradeless teaching and learning changes the way we think about building community, curriculum content, and how students take ownership of their learning.

Building Community

A sense of belonging is essential to student success, especially in the first year. Belonging leads to higher performance, but even more importantly, is linked to a student’s persistence and overall mental health and well-being (Gopalan and Brady, 2019). Through the reflective writings, many of the participants in the FLC reported that, without the use of grades as a tool to potentially divide students, other aspects of “success” in a course could take center stage. Building community took two main forms: student community within the studio and professor as learning partner.

With the removal of traditional grading practices and a reorientation toward self-assessment, a greater sense of community was felt by professors and students alike. Andy noted that, “I believe students welcome the relief from external judgment and that this instills a sense of community. Students who feel part of that community are happier and more likely to have fond and lasting memories of the course.” Other FLC participants reported a similar feeling that—while a grade might feel like an independent project within a class, an avenue between professor and student—gradeless assessment, in the form of self-reflection and peer feedback, has the potential to be a community (classroom) project.

Additionally, Brian noticed that not only was the sense of community something he sought to cultivate with his students across the semester, but it is also something that he is profoundly implicated in and impacted by:

When the course acts like a “learning community,” each person’s growth and learning contributes to everyone else's. My own role in the course/community is to learn from every generation of students who push me to improve on my grasp of the course material and to strive in becoming a more sensitive and effective teacher. I am learning with my students.

Similarly, Andy deepened his understanding of community:

I turned to writing as a tool to measure student understanding much more than I have in the past. Maybe just as importantly, this experience has served to expand my own personal thinking and understanding to other department initiatives such as parallel teaching across multiple courses and departmental outcomes such as “community.”His notion of parallel teaching would mean that professors teaching the same courses would be matched so that they could share teaching insights to “propel inquiry and synthesis.”

The Values and Challenges of Reflection, Self-Assessment, and Feedback

Faculty introduced a more structured form of written reflection into their gradeless courses than they had previously. Andy noted that:

The focus on written reflection was an opportunity to gain insight into questions that had been brewing in my mind for years. It was a chance for students to go further in their thinking about synthesis and inquiry. I found the prompts and answers to the questions to be very revealing for me personally. Responses fit into three categories: students who have gained fluency and understanding of the verbal content, students who have memorized terms and definitions, and students who are struggling with both verbal fluency and understanding.

Brian has been working to integrate self-assessment into his course for many years, in part through a tool called the “individual process book” (see above). Brian noted that the process books are

[i]n essence… public and private opportunities to watch growth captured in a linear view of the student working. Because students are asked to take photos of their work as they are working, it “slows the class down” and “forces students to look at unexpected intervals… and in doing so, NOTICE things.

However, across most of these highlighted courses, faculty also noted that the introduction of slowing down or adding additional reflective writing and documentation also created challenges for adding these rich alternate forms of assessment into an already packed fifteen-week curriculum. The professors in the FLC often shared a sense of overwhelm, seeing the value of written and reflective assessment while also keeping up with the expectation to deliver their established curriculum. Micki noted that:

The time commitment of self-reflection was added to an already full course. [There was a] problem of what to take out to replace the writing/self-reflection component. As much as I would have liked to provide some class time for self-reflective writing, I could not omit any content to replace the time needed for student self-reflection.

Andy noted that “it also requires a time commitment for both faculty and students that comes at a loss of making work.” In contrast, James argued that a shift to feedback within a skill-based learning environment has been unique. He suggests that there is no diminishing of skill-based learning within the gradeless environment.

Students’ sample responses to the gradeless environment appear to support James’s claim. While the following quotes from his students in response to a set of prompts are not representative of all students, they illustrate student understanding of the value of the instructional interventions in their own learning. One student noted that:

I learned to value the feedback and critique of my classmates and professor over a grade, because their input is what helps me refine my work and push myself to improve. Additionally, I learned how to give constructive and important critique to my classmates.

Another student addressed the value of combining feedback with skill-building: “Self-assessment makes it much easier to individually understand how far I've developed my skills. Professors still make clear whether or not I am succeeding with feedback.” Clearly, future research will need to incorporate student voice, not only through individual responses, but also in the overarching pilot.

Conclusion

This brief analysis of two emergent themes in the FLC research is small-scale. However, the themes that emerged—building community and reflective practices—suggest that faculty instructional practices, while somewhat different and unique, supported different types of reflection, self-assessment, feedback, and community-building in a gradeless context. This does not mean that it is impossible to promote and sustain such instructional interventions in a traditional (i.e., graded) setting, but it suggests that a gradeless context combined with such interventions can provide a conducive setting for students to grow as learners and makers through alternative assessment. And without such interventions, a gradeless approach may not necessarily contribute to student learning.

The continuation and expansion of the Gradeless Assessment Pilot requires administrative support at all levels. Indeed, administrative support from the former associate provost and department chairs was critical to the launch and implementation of the pilot. However, further support is essential in order to address the structural changes necessary to embed alternative assessment into the curriculum and pave the way for institutionalizing alternative assessment in art and design.

References

Bishop-Clark, C. U., Dietz, B., & Cox, M. D. (2014). Developing the scholarship of teaching and learning using faculty and professional learning communities. Learning Communities Journal, 6, 31–53.

Bhambra, G. K, Nişancıoğlu, K., & Gebrial, D. (Eds.). (2018). Decolonizing the university. Pluto Press.

Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19897622

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985253

Martin-Thomsen, T. C., Scagnetti, G., McPhee, S., Akenson, S. B., & Hagerman, B. ( 2021). The scholarship of critique and power. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 9(1), 279–93. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.19

McArthur, J. (2019). Assessment for social justice: Perspectives and practices within higher education. Bloomsbury Academic.

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2020, January). A new decade for assessment: Embedding equity into assessment praxis (Occasional Paper No. 42). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centered framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45:4, 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

O’Donovan, B. M., den Outer, B., Price, M., & Lloyd, A. (2021). What makes good feedback good? Studies in Higher Education, 46(2), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1630812

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2022). The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 47:3, 656–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2017). “It'd be useful, but I wouldn't use it”: Barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

Verwoord, R., & Poole, G. (2016). The role of small significant networks and leadership in the institutional embedding of SoTL. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20190

Additional FLC Participants

Worth Bracken- Participant (History of Art and Design 111)

Gloria Fan Duan (Quantitative research study on Gradeless Assessment Pilot to be published in the future)

Gaia Hwang (Chair, Grad Com-D, research on Gradeless Assessment Pilot to be published in the future)

Andy Lenaghan- Participant (Foundation)

Kyle Williams- Participant (Foundation)

Karyn Zieve (Assistant Dean, SLAS)

Administrative Support for Pilot

Gaia Hwang, Chair, Graduate Communications Design

Camille Martin-Thompsen, Associate Provost

Leslie Mutchler, Chair, Foundation