<--

Caroline Matthews

Inclusive Pedagogy: Creating adaptive spaces for a spectrum of learners to access metacognitive skills

Caroline Matthews

Abstract

This research delves into the crucial role of the initial student-instructor conversation in ensuring classroom success, particularly for Pratt students with learning differences. These conversations commence with an Accommodation Letter issued by the institute’s Learning/Access Center (L/AC). The letter specifies the support granted, including accommodations like extended testing time and excused absences. However, since it is a legal document aimed to blanket any higher education setting, it is not tailored to the specific demands of learning environments like studio art classes. Open dialogue between students and instructors is therefore essential to determine where support is needed, outside of the standardized accommodations available to them.

This paper, a combination of personal essays and research-driven observations, advocates for educators to prioritize creating safe and inclusive classroom environments through trauma-informed teaching strategies and insights from research on cultural and emotional intelligence. The objective is to foster empathy and empower students to articulate their learning needs. By helping students better understand themselves, their motivations, and their behaviors, educators can facilitate advocacy for necessary accommodations. This research highlights the demand among instructors for accessible resources to support the well-being of their students. The learning scenarios offered in this paper act as a potential guide to effectively respond to unique classroom situations.

Keywords

Accessible education, accommodation, active teaching, classroom collaboration, pedagogy, resilience, inclusivity

Through personal essay writing (which will be indicated in italics) and research analysis, this work compiles secondary research, interviews, and classroom observations to support faculty of the modern classroom as industry-expert educators, not as anthropologists or psychologists of the student experience. This paper aims to raise awareness and expand the conversation concerning the adaptive educational environment in response to students with learning disabilities.

It was January 2022. I was appointed a second class three weeks before the academic semester would begin. COVID-19 restrictions kept us home our first week of classes. New faculty onboarding was exclusively online: a mix of helpful Zoom meetings and specific yet generic emails. But one interaction was hurtful.

“Ugh, I have three accommodation letters,” said one faculty member before a Zoom meeting officially began. Her tone felt burdened, and others chimed in too. Not a single comment was positive. I, of course, as new faculty absorbing every detail and interaction to build my own experience, became terrified of this letter. I also felt relieved I had not received one.

Fast forward six months. I’m feeling a little more at ease as a new teacher, and it’s one week before my second semester of teaching. I receive six emails with identical timestamps and subject lines: “Fwd: CONFIDENTIAL RE: Student Name: ID - L/AC Accommodations Letter.” That semester, I would teach a mix of second- and third-year undergrad and second-year graduate students.

The L/AC is a specific department of Pratt designed to ensure comprehensive accessibility for students with or without disabilities. They are the sole office responsible for approving the state-mandated accommodations for students. Their support enables all students unrestricted and engaged involvement in all aspects of Pratt's academic and campus life.

The L/AC at Pratt provides students with Accommodation Letters. These are emailed to their instructors before the school year begins and outline what modifications the instructor is required by law to provide for the student. This is in direct response to legislation mandating equal access for persons with disabilities. This involves education. Amendments to the act in 2008 and 2016 included mental health conditions that may not have a lifelong impact. Examples of episodic conditions include but are not limited to: diabetes, Crohn’s disease, Bipolar Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, and many other physical and mental health conditions.

Reasonable accommodations refer to adjustments or modifications made to programs, facilities, or curricula to guarantee equal access for students with documented disabilities. Some examples of reasonable classroom accommodations are extended time for testing and certain assignments, the use of assistive technology, classroom relocation, and providing a note-taker. According to the Pratt L/AC, “All accommodations are determined on a case-by-case basis based on documentation review, interview(s) with the student, and professional review” (Pratt Institute, 2023).

I still felt very disconnected from the faculty after completing a semester of teaching. I needed confidants. Not knowing what to expect except a stipend and potential for publication, I applied to the Center for Teaching and Learning’s Faculty Learning Lab and partnered with Anna Philip, Assistant Adjunct Faculty, School of Fashion. To me, her goal felt in line with my own: to “destigmatize having a learning difference by advocating for open communication between students and faculty” (personal communication, November 10, 2023). Change doesn’t work alone. Creating awareness about the harmful effects of the stigmas attached to learning differences wasn’t going to drive change on its own. The strategy for change needs to empower both faculty and students.

According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, creating inclusive and supportive learning environments for diverse learners lowers the academic effects of depression, which include a decrease in student performance and an increase in dropout rate. An inclusive classroom curriculum is a creative approach to teaching. The instructor’s role is to create a learning environment where everyone can learn. It’s deliberate and involves personal interactions, adapted course content, recurring feedback between student and faculty, and culturally responsive pedagogical practices (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). According to Peoples et al. (2021), from the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, the principles of culturally responsive practices are:

![]()

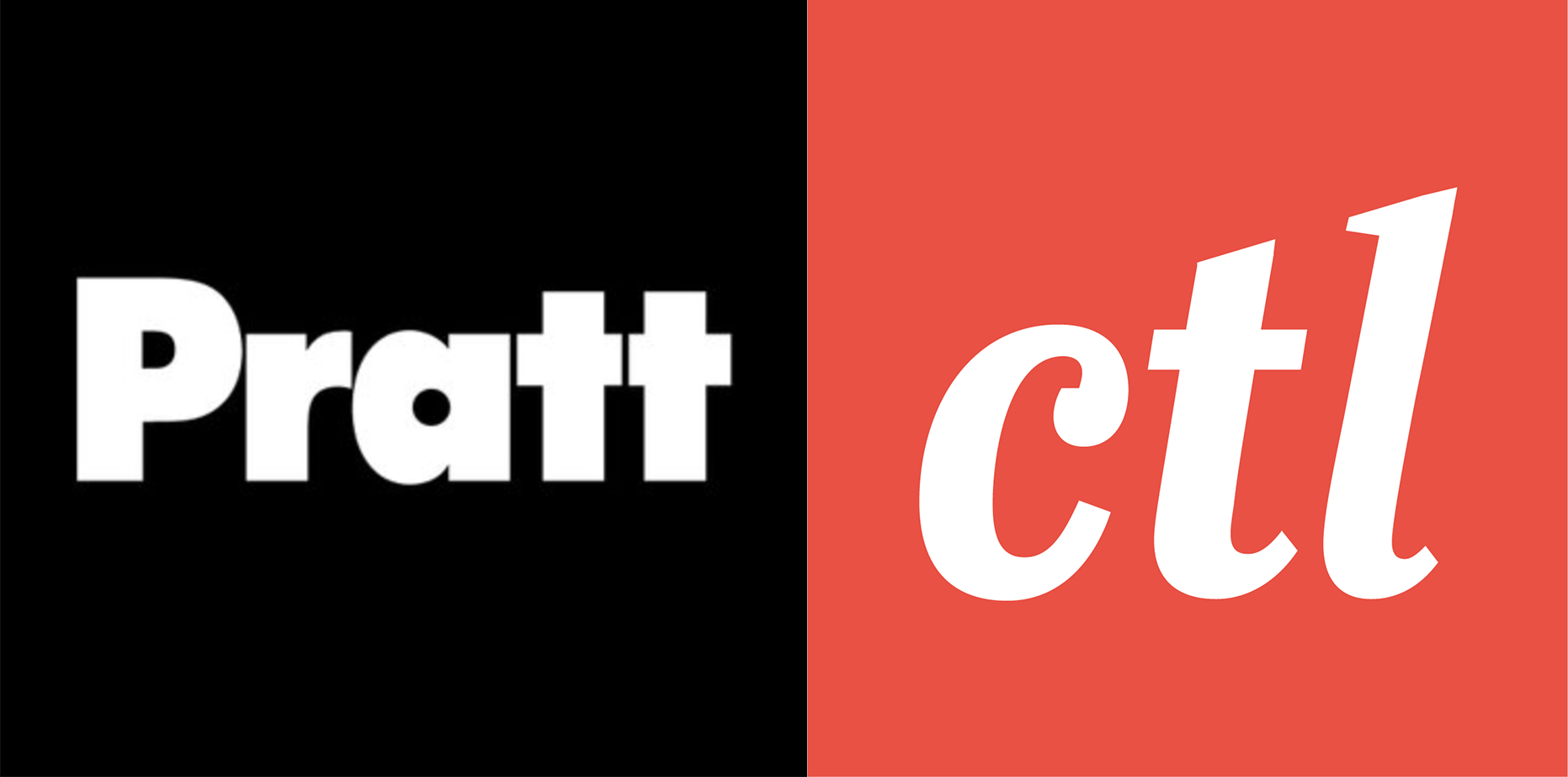

Note: Transformation Design (represented in the figure above as “A” and “B”) is a year-long MFA Communications Design course in two semesters, DES-730A and DES-730B.

The classroom has evolved since Pratt’s inaugural class in 1887: most drafting tables have been replaced by powerful 3D-rendering computers, typewriters have been switched out with tablets, and so on. Teaching or studio assistants are no longer part of Pratt's pedagogy. This article defines pedagogy as the cumulation of teaching methods that form the framework of a classroom. Active teaching methods complement change by supporting collaborative decision-making and learning. Purdue University’s Wilmeth Active Learning Center (2023) recognizes active teaching methods as frameworks that support:

![]()

Note: Dry collodion negative. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

![]()

Note: Black and white photograph. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

![]()

Note: Keith Boro. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library

![]()

Note: Jeanne Strongin. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

Figure 6

Third-year Undergraduate Students Engage in Collaborative Making Activity, April 2023

![]()

Note: Exercise Adapted from Conditional Design Workbook, 2013.

Active teaching methods, simply put, are exactly as they sound: active. They facilitate students in combating passive classroom behaviors like zoning out or “multitasking” with screens and unrelated course material. Passive teaching methods include the didactic lecture, typically found in STEM-based classrooms, or instructor-led critique in studio art courses. Active teaching demands agility and dynamism, requiring the instructor to act as a facilitator rather than the boss of the classroom. Student-led discussions and open-ended questions foster meaningful dialogue within dynamic classrooms, consequently supporting the exploration of ideas.

It was my first semester teaching and I wanted to make an impression among a small group of design faculty during a Zoom onboarding. Despite knowing very little, I wanted to teach the principles of accessible design. Accessible design is an approach that results in the development of products or experiences that foster independence in all users. Teaching students to include accessibility at the forefront of their projects is embedded in the curriculum at Pratt, no matter the department. I wanted to push students to think critically about user types beyond themselves. What happens when a visually impaired adult uses the shampoo bottle you designed? Can a universal interaction meet the same goal of usability?

A close friend was dyslexic and new in his role as a senior software engineer. We talked often about impostor syndrome and the push-and-pull inner dynamics of the phenomenon. To set himself apart, he pushed his manager to implement Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) across the company’s digital product offerings. Beyond color contrast and responsive web pages, I didn’t know the nuances of WCAG. I was overwhelmed that I’d piped up in a faculty meeting and suggested I knew what I was talking about!

I was initially connected to Megan Cash, Adjunct Assistant Professor in Undergraduate Communications Design, by a student who attributed her understanding of designing for differences and inclusivity to CDILL-412 Designing for Kids. The student disclosed the reason for her accommodation in my class was dyslexia. Megan taught me that as we reach greater acceptance of designing with disabled users in mind, the language and culture will always be in flux. This fluctuation Megan referenced felt more like a process to me. Process is development. We are allowed to make mistakes as we develop, as long as genuine and gentle curiosity drives that development.

By connecting accommodation to accessibility, I took an active approach to adjust my framework for teaching accessible design. I needed to keep learning while still teaching at the same time, so I required students to share their independent knowledge with the class. It felt a little terrifying given I was newly appointed visiting instructor of a world-renowned university; I backed off as the authority and took a seat alongside my students. Together, we reflected on what biases we needed to unlearn from our previous education. Together, we were in control of our learning environments.

“Divergent cultural backgrounds or students unfamiliar with higher education, like a masters-level student from China or a first-year undergraduate student directly out of high school, can affect the maturity levels of learners. They do not have a strong understanding that agency is defined by responsibilities, and this may be the first time in their lives that they hold complete freedom of those responsibilities” (B. Brooks, personal communication, December 2023).

“Faculty do not have education degrees; we are leaders in our field,” says Associate Professor Damon Chaky (personal communication, April 17, 2023). Chaky, an educator since 1993 and Columbia Science Fellow, enjoys making science relevant and exciting for nonmajors. His courses are STEM-based, meaning they use hands-on learning to enhance problem-solving skills. These types of classes are integral in developing metacognitive skills like time management, ownership of unique learning style, and self-assessment through reflection at the higher education level. He’s adopted tools supported by the Institute, like Canvas for learning management and Kurzweil for literary support. His teaching style and candor are beloved: In 2018, he received Pratt’s Distinguished Teacher Award. Although it is unconfirmed by the Institute, Chaky feels students with Accommodation Letters seek out his class because of his adaptability to their learning needs. “I think it’s been better for everybody,” says Chaky, who respects that some students can’t participate verbally or comprehend reading assignments heavy in jargon.

Small modifications in course design lead to lasting cognitive outcomes. James M. Lang, author of Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons From the Science of Learning (2016), feels these adjustments promote active learning, engagement, and metacognition, ultimately contributing to students' retention and understanding of course material in the long term. Perhaps this is a form of resiliency in a changing educational landscape with classrooms or supplemental learning streamed through video.

![]()

The “Me as a Learner” survey, originally crafted by Philip, is just one response to inclusive pedagogy. It addresses student backgrounds and learning experiences and recognizes that in-class participation may look very different from student to student. The original intent of the survey was to measure the hypothesis that students are unaware that Pratt’s L/AC is available to all students. Upon further development through a series of multiple-choice questions, the survey also assesses their prior knowledge and helps them determine what they need to feel successful in the course. Ultimately, students share with their instructor the type of learner they think they are: visual, auditory, or tactile. Its original iteration was a follow-up after students were introduced in-class to the L/AC to find out if students were aware of the institutional support. It was also used as a tool for gathering quantitative data from approximately thirty undergraduate and graduate students to determine their awareness of the support or that they may need support. Despite its original intent, it can successfully be reformatted and provided to students at the start of each semester. Results can steer educators to tailor their at-home learning methods to videos or podcasts instead of the standard academic or technical readings. Perhaps patterns may be observed over the years and curriculum formats may iterate into new mediums, creating a library of inclusive material to support different kinds of learners.

![]()

A tactic that faculty can use to directly support resilient learners is to intentionally research, select, and share diverse authors from historically underrepresented people who speak across genders, cultures, socioeconomic statuses, ages, and religions. These references cultivate diverse ideas and demonstrate to students the importance of studying conflicting viewpoints from opposing perspectives.

Resilience should not be regarded solely as a personality trait; while it may be perceived as an end result, it is more accurately defined as an adaptive process supported by various skills, strengths, and characteristics. Resilience operates along a spectrum, and individuals have the capacity to enhance their resilience throughout their lives (American Psychological Association APA, 2003).

In conversation, one Pratt faculty member shared how he was able to reframe the idea of meeting students at their level: “It’s not really the students that have to be flexible, it’s me” (J. Osborn, personal communication, September 2023). Recognizing what’s happening around us in the world, how might instructors and students acknowledge global issues? How might we better recognize that culturally charged events affect student identity? How might we combine this agency with work/life balance? James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, says the answer is “habit stacking,” or connecting a new habit with an activity or habit that is already routine (Clear, 2018).

For example, if a student is always late with a to-go cup in hand, perhaps they could stack the habit of arriving fifteen minutes early to get their morning coffee. Reflection is a key supplement to iteration. Consider starting each class with a warm up exercise that promotes reflection. Perhaps it is tied to current events, the assignment they are currently working on, habits they want to break, or future assignments.

As easy as habit stacking may sound, the antidote to stigma is not resilience. It’s advocacy. Anna Philip and I had the opportunity to brainstorm with Jason Wallin, Director of Upper School at Churchill School and Center. The Churchill School and Center is a private institution in Manhattan catered to support students with learning disabilities under IEPs. In working with students who have IEPs, and who later may seek out accommodations at the college level, he shared, “When students understand themselves, their motivations, and their behaviors, they are more likely to advocate for themselves” (J. Wallin, personal communication, June 2023).

I am thrilled to pivot from “stigmatization” to “advocacy.” How might we support students with accommodation letters in having the conversations with instructors? How might we support struggling students who do not have accommodation? How might we support instructors with available resources for students with accommodation?

Instructors at Pratt are encouraged to flag students in a workflow browser-based system called Starfish. This portal allows faculty to communicate with students about their classroom behaviors in a non-verbal yet authoritative manner. Various flags like “Well Being” and “Absence/Tardiness” are selected by faculty based on student behaviors. Each flag alerts the appropriate student services. That service sends an email to the student encouraging them to take advantage of on-campus services in response to an instructor’s flag.

![]()

Note: Sample Email Autogenerated to Starfish-Flagged Student

My colleague and collaborator, Anna Philip, was instrumental by sharing her personal anecdotes from the classroom: “I want faculty to have proper training and supportive tools for how to best address different learning needs in the classroom, like providing talking points, writing templates when using Starfish, and information about the federal disability act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act,” she said (A. Phillips, personal communication, November 16, 2023).

In my career change from project manager at CNN to full-time faculty, it seemed logical that incorporating current events into the practicum would be unique to my pedagogy. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, I wanted to use news media as a conduit for new learning experiences. I was woefully unprepared for what happened.

As a new teacher, I was aware that my written communication was stronger than my verbal, so I sent a weekly email to students outlining assignments for the next class. One of my students was Ukrainian and responded that he would not be attending class to be available for his family. I asked how I or the class could help. He responded that he was asking our department if he could post a donation box at the entrance of the building. I wrote the department contact he mentioned for clarity. Utilizing the fact that the student would not be present that week, I planned to foster a class discussion: “How can we help a member of our community?”

Some students confessed they were avoiding reports altogether in fear of misinformation. Others were very uncomfortable discussing the politics of sides. There was laughing while they tried to formulate their thoughts. I understand that laughter can be a coping mechanism for fear. I didn’t understand, however, that it is a lot to ask a student to question how they receive information. I felt it was my duty as an instructor of an international community to not ignore the closeness of war. I quite honestly forced it into the classroom as broadly and gently as I thought possible: by utilizing a rudimentary technique we just learned, a mood board of up to ten images, to relay the sentiment and feelings of an informational campaign.

We formulated the assignment together in class—uncomfortably, everyone agreed to develop either a) an awareness campaign or b) a fundraising campaign—and I typed up the guidelines and made them available to students by message board. "If anything, this will be an exercise in working with a subject matter or client that makes you uncomfortable," I said. "Please email me your questions and concerns." I received no questions or concerns.

The co-created guidelines directly influenced the strategy of the Ukrainian student; when it was his turn the following week, he shared shocking images of destruction and displaced refugees. When he became emotional, I immediately thanked the class for participating in the exercise and I was sorry for any pain it caused. “If anyone wanted to continue their campaigns, I'd be happy to guide them outside of class time. Please reach out.”

No one reached out. What was I thinking?! Why did I find it appropriate to use pain as a learning tool?

This experience clarified my role in the classroom. Facilitator or professor, whatever I want to call myself, I hold tremendous power. As a result of this experience, I jumped at the chance, when offered by Pratt’s Center for Teaching and Learning, to earn a professional certification in Trauma Informed Learning from the University of Florida. I am grateful for this student who inadvertently challenged my thinking as a global citizen and holistic teacher. Thank you!

Graduate students are six times more likely to experience moderate to severe anxiety and depression than the general population (Evans et al., 2018). Stressors that contribute to poor mental health specifically among graduate students include:

The L/AC supports all students, regardless of their identified ability or level of study. Like the Writing Center, the L/AC provides services to help students perform their best, no matter their present level of performance. This is an integral part of “meeting students where they are at,” a form of pedagogy described by Tom Klinkowstein, Adjunct Professor of Communications Design (personal communication, July 2023). Klinkowstein has been a Pratt instructor for thirty-four years. He’s witnessed how changes in technology alter the process of design. Likewise, he’s seen the opportunities unearthed by changes in disability legislation and policy. “Care before you dare” is another staple of Klinowstein’s classroom strategy. First, meet the students at their level. Modify assignments so they are approachable to all learners. Treat confidence as a skill. Support first, then push them to take risks.

Klinowstein’s pedagogy supports what author and psychologist Carol Dweck (2006) calls the “growth mindset” (p. 5). Mindsets are your collection of thoughts and beliefs that shape your thought habits; they affect how you think, what you feel, and what you do. Mindsets impact how you make sense of everything: your environment, the people you choose to surround yourself with, your own behaviors and thoughts.

“For decades, I’ve been studying why some people succeed while people, who are equally talented, do not. And over the years I’ve discovered that people’s mindsets play a crucial role in this process” (Dweck, 2006, p. 32). The growth mindset is learning-centered and documented through a series of milestones from acknowledgment of the required skill to practice, failure, goal setting, and eventual mastery.

Goal setting is a form of advocacy. This can be part of the initial conversation. Ask the student what they already know and what new skills they want to learn. Throughout the semester, chunk studio assignments into manageable pieces. For example, consider one overall project broken into multiple parts. Allow multiple ways for students to demonstrate their learning and understanding.

In March 2022, in my third semester of teaching, Anna Philip and I were invited by CTL to lead a Zoom discussion open to all Pratt faculty. We knew we needed a partner and asked Anna Riquier, Associate Director for Accessibility, to be our guest. Titled Faculty Spotlight: Structuring Inclusive Classrooms to Support Diverse Learners, the intention was to teach the basic frameworks for cultivating inclusive classroom experiences for higher education art students. The goal was to help them build confidence to iterate and adjust to their student dynamic. The workshop explored the overarching principles to ensure that classrooms provide community, inclusion, and belonging. These include reframing, iteration, reflection, and adjusting how we share and receive information.

It sounds incredibly optimistic, but I hope conversations like these sparked action and collaboration. Throughout this process of investigation, I discovered new challenges, like the oversaturation of messaging and information. Rest affects performance. Encouraging risk is required when connecting to graduate students more so than undergraduate. Although eager to formulate a network of events and shareable digital teaching tools—I’ve always wanted to host a podcast!!!—I must respect the process of listening, observing, and building authentic relationships. The results of this effort are years in the making, and patience is required.

It Starts With a Clear Call to Action, Highly Visible to All Faculty: Require Integration of Student Engagement Techniques Within Studios and Classrooms

This research delves into the crucial role of the initial student-instructor conversation in ensuring classroom success, particularly for Pratt students with learning differences. These conversations commence with an Accommodation Letter issued by the institute’s Learning/Access Center (L/AC). The letter specifies the support granted, including accommodations like extended testing time and excused absences. However, since it is a legal document aimed to blanket any higher education setting, it is not tailored to the specific demands of learning environments like studio art classes. Open dialogue between students and instructors is therefore essential to determine where support is needed, outside of the standardized accommodations available to them.

This paper, a combination of personal essays and research-driven observations, advocates for educators to prioritize creating safe and inclusive classroom environments through trauma-informed teaching strategies and insights from research on cultural and emotional intelligence. The objective is to foster empathy and empower students to articulate their learning needs. By helping students better understand themselves, their motivations, and their behaviors, educators can facilitate advocacy for necessary accommodations. This research highlights the demand among instructors for accessible resources to support the well-being of their students. The learning scenarios offered in this paper act as a potential guide to effectively respond to unique classroom situations.

Keywords

Accessible education, accommodation, active teaching, classroom collaboration, pedagogy, resilience, inclusivity

Through personal essay writing (which will be indicated in italics) and research analysis, this work compiles secondary research, interviews, and classroom observations to support faculty of the modern classroom as industry-expert educators, not as anthropologists or psychologists of the student experience. This paper aims to raise awareness and expand the conversation concerning the adaptive educational environment in response to students with learning disabilities.

It was January 2022. I was appointed a second class three weeks before the academic semester would begin. COVID-19 restrictions kept us home our first week of classes. New faculty onboarding was exclusively online: a mix of helpful Zoom meetings and specific yet generic emails. But one interaction was hurtful.

“Ugh, I have three accommodation letters,” said one faculty member before a Zoom meeting officially began. Her tone felt burdened, and others chimed in too. Not a single comment was positive. I, of course, as new faculty absorbing every detail and interaction to build my own experience, became terrified of this letter. I also felt relieved I had not received one.

Fast forward six months. I’m feeling a little more at ease as a new teacher, and it’s one week before my second semester of teaching. I receive six emails with identical timestamps and subject lines: “Fwd: CONFIDENTIAL RE: Student Name: ID - L/AC Accommodations Letter.” That semester, I would teach a mix of second- and third-year undergrad and second-year graduate students.

The L/AC is a specific department of Pratt designed to ensure comprehensive accessibility for students with or without disabilities. They are the sole office responsible for approving the state-mandated accommodations for students. Their support enables all students unrestricted and engaged involvement in all aspects of Pratt's academic and campus life.

The L/AC at Pratt provides students with Accommodation Letters. These are emailed to their instructors before the school year begins and outline what modifications the instructor is required by law to provide for the student. This is in direct response to legislation mandating equal access for persons with disabilities. This involves education. Amendments to the act in 2008 and 2016 included mental health conditions that may not have a lifelong impact. Examples of episodic conditions include but are not limited to: diabetes, Crohn’s disease, Bipolar Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, and many other physical and mental health conditions.

Reasonable accommodations refer to adjustments or modifications made to programs, facilities, or curricula to guarantee equal access for students with documented disabilities. Some examples of reasonable classroom accommodations are extended time for testing and certain assignments, the use of assistive technology, classroom relocation, and providing a note-taker. According to the Pratt L/AC, “All accommodations are determined on a case-by-case basis based on documentation review, interview(s) with the student, and professional review” (Pratt Institute, 2023).

I still felt very disconnected from the faculty after completing a semester of teaching. I needed confidants. Not knowing what to expect except a stipend and potential for publication, I applied to the Center for Teaching and Learning’s Faculty Learning Lab and partnered with Anna Philip, Assistant Adjunct Faculty, School of Fashion. To me, her goal felt in line with my own: to “destigmatize having a learning difference by advocating for open communication between students and faculty” (personal communication, November 10, 2023). Change doesn’t work alone. Creating awareness about the harmful effects of the stigmas attached to learning differences wasn’t going to drive change on its own. The strategy for change needs to empower both faculty and students.

According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, creating inclusive and supportive learning environments for diverse learners lowers the academic effects of depression, which include a decrease in student performance and an increase in dropout rate. An inclusive classroom curriculum is a creative approach to teaching. The instructor’s role is to create a learning environment where everyone can learn. It’s deliberate and involves personal interactions, adapted course content, recurring feedback between student and faculty, and culturally responsive pedagogical practices (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). According to Peoples et al. (2021), from the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, the principles of culturally responsive practices are:

- Communication of high expectations

- Active teaching methods including small-group instruction and student-controlled discourse

- Practitioner as facilitator

- Cultural sensitivity and inclusion of culturally and linguistically diverse students

- Reshaping the curriculum of delivery of services

Figure 1

Assignment Framework and Goals, 2023

Assignment Framework and Goals, 2023

Note: Transformation Design (represented in the figure above as “A” and “B”) is a year-long MFA Communications Design course in two semesters, DES-730A and DES-730B.

The classroom has evolved since Pratt’s inaugural class in 1887: most drafting tables have been replaced by powerful 3D-rendering computers, typewriters have been switched out with tablets, and so on. Teaching or studio assistants are no longer part of Pratt's pedagogy. This article defines pedagogy as the cumulation of teaching methods that form the framework of a classroom. Active teaching methods complement change by supporting collaborative decision-making and learning. Purdue University’s Wilmeth Active Learning Center (2023) recognizes active teaching methods as frameworks that support:

- small-group student-led discussions

- self-reflection as the identifier for both intellectual and personal growth

- work completed as partners

- sharing through a variety of formats beyond verbal

Figure 2

Pratt Student Studies Still Life Through Painting, 1900

Pratt Student Studies Still Life Through Painting, 1900

Note: Dry collodion negative. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

Figure 3

Pratt Classroom, 1900

Pratt Classroom, 1900

Note: Black and white photograph. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

Figure 4

Faculty Demonstrates Food Science and Management Curriculum, 1983

Faculty Demonstrates Food Science and Management Curriculum, 1983

Note: Keith Boro. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library

Figure 5

John Pai, Former Director of the Division of Fine Arts at Pratt, Critiques Student Prototypes, 1984

John Pai, Former Director of the Division of Fine Arts at Pratt, Critiques Student Prototypes, 1984

Note: Jeanne Strongin. Pratt Institute Archives, Pratt Institute Library.

Figure 6

Third-year Undergraduate Students Engage in Collaborative Making Activity, April 2023

Note: Exercise Adapted from Conditional Design Workbook, 2013.

Active teaching methods, simply put, are exactly as they sound: active. They facilitate students in combating passive classroom behaviors like zoning out or “multitasking” with screens and unrelated course material. Passive teaching methods include the didactic lecture, typically found in STEM-based classrooms, or instructor-led critique in studio art courses. Active teaching demands agility and dynamism, requiring the instructor to act as a facilitator rather than the boss of the classroom. Student-led discussions and open-ended questions foster meaningful dialogue within dynamic classrooms, consequently supporting the exploration of ideas.

It was my first semester teaching and I wanted to make an impression among a small group of design faculty during a Zoom onboarding. Despite knowing very little, I wanted to teach the principles of accessible design. Accessible design is an approach that results in the development of products or experiences that foster independence in all users. Teaching students to include accessibility at the forefront of their projects is embedded in the curriculum at Pratt, no matter the department. I wanted to push students to think critically about user types beyond themselves. What happens when a visually impaired adult uses the shampoo bottle you designed? Can a universal interaction meet the same goal of usability?

A close friend was dyslexic and new in his role as a senior software engineer. We talked often about impostor syndrome and the push-and-pull inner dynamics of the phenomenon. To set himself apart, he pushed his manager to implement Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) across the company’s digital product offerings. Beyond color contrast and responsive web pages, I didn’t know the nuances of WCAG. I was overwhelmed that I’d piped up in a faculty meeting and suggested I knew what I was talking about!

I was initially connected to Megan Cash, Adjunct Assistant Professor in Undergraduate Communications Design, by a student who attributed her understanding of designing for differences and inclusivity to CDILL-412 Designing for Kids. The student disclosed the reason for her accommodation in my class was dyslexia. Megan taught me that as we reach greater acceptance of designing with disabled users in mind, the language and culture will always be in flux. This fluctuation Megan referenced felt more like a process to me. Process is development. We are allowed to make mistakes as we develop, as long as genuine and gentle curiosity drives that development.

By connecting accommodation to accessibility, I took an active approach to adjust my framework for teaching accessible design. I needed to keep learning while still teaching at the same time, so I required students to share their independent knowledge with the class. It felt a little terrifying given I was newly appointed visiting instructor of a world-renowned university; I backed off as the authority and took a seat alongside my students. Together, we reflected on what biases we needed to unlearn from our previous education. Together, we were in control of our learning environments.

“Divergent cultural backgrounds or students unfamiliar with higher education, like a masters-level student from China or a first-year undergraduate student directly out of high school, can affect the maturity levels of learners. They do not have a strong understanding that agency is defined by responsibilities, and this may be the first time in their lives that they hold complete freedom of those responsibilities” (B. Brooks, personal communication, December 2023).

“Faculty do not have education degrees; we are leaders in our field,” says Associate Professor Damon Chaky (personal communication, April 17, 2023). Chaky, an educator since 1993 and Columbia Science Fellow, enjoys making science relevant and exciting for nonmajors. His courses are STEM-based, meaning they use hands-on learning to enhance problem-solving skills. These types of classes are integral in developing metacognitive skills like time management, ownership of unique learning style, and self-assessment through reflection at the higher education level. He’s adopted tools supported by the Institute, like Canvas for learning management and Kurzweil for literary support. His teaching style and candor are beloved: In 2018, he received Pratt’s Distinguished Teacher Award. Although it is unconfirmed by the Institute, Chaky feels students with Accommodation Letters seek out his class because of his adaptability to their learning needs. “I think it’s been better for everybody,” says Chaky, who respects that some students can’t participate verbally or comprehend reading assignments heavy in jargon.

Small modifications in course design lead to lasting cognitive outcomes. James M. Lang, author of Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons From the Science of Learning (2016), feels these adjustments promote active learning, engagement, and metacognition, ultimately contributing to students' retention and understanding of course material in the long term. Perhaps this is a form of resiliency in a changing educational landscape with classrooms or supplemental learning streamed through video.

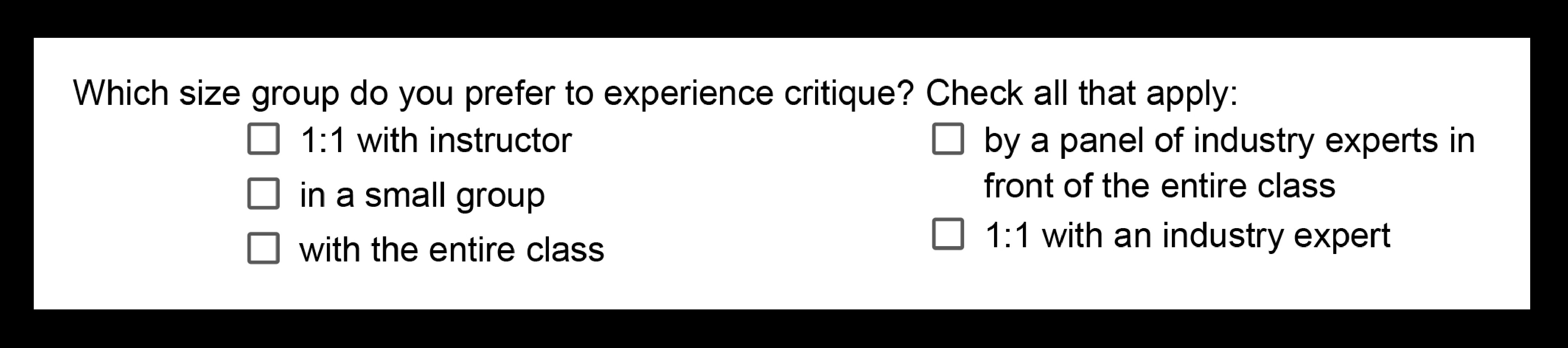

Figure 7

Survey Sample Question, Fall 2022

Survey Sample Question, Fall 2022

The “Me as a Learner” survey, originally crafted by Philip, is just one response to inclusive pedagogy. It addresses student backgrounds and learning experiences and recognizes that in-class participation may look very different from student to student. The original intent of the survey was to measure the hypothesis that students are unaware that Pratt’s L/AC is available to all students. Upon further development through a series of multiple-choice questions, the survey also assesses their prior knowledge and helps them determine what they need to feel successful in the course. Ultimately, students share with their instructor the type of learner they think they are: visual, auditory, or tactile. Its original iteration was a follow-up after students were introduced in-class to the L/AC to find out if students were aware of the institutional support. It was also used as a tool for gathering quantitative data from approximately thirty undergraduate and graduate students to determine their awareness of the support or that they may need support. Despite its original intent, it can successfully be reformatted and provided to students at the start of each semester. Results can steer educators to tailor their at-home learning methods to videos or podcasts instead of the standard academic or technical readings. Perhaps patterns may be observed over the years and curriculum formats may iterate into new mediums, creating a library of inclusive material to support different kinds of learners.

Figure 8

____ as a Learner Worksheet, Fall 2023

____ as a Learner Worksheet, Fall 2023

A tactic that faculty can use to directly support resilient learners is to intentionally research, select, and share diverse authors from historically underrepresented people who speak across genders, cultures, socioeconomic statuses, ages, and religions. These references cultivate diverse ideas and demonstrate to students the importance of studying conflicting viewpoints from opposing perspectives.

Resilience should not be regarded solely as a personality trait; while it may be perceived as an end result, it is more accurately defined as an adaptive process supported by various skills, strengths, and characteristics. Resilience operates along a spectrum, and individuals have the capacity to enhance their resilience throughout their lives (American Psychological Association APA, 2003).

In conversation, one Pratt faculty member shared how he was able to reframe the idea of meeting students at their level: “It’s not really the students that have to be flexible, it’s me” (J. Osborn, personal communication, September 2023). Recognizing what’s happening around us in the world, how might instructors and students acknowledge global issues? How might we better recognize that culturally charged events affect student identity? How might we combine this agency with work/life balance? James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, says the answer is “habit stacking,” or connecting a new habit with an activity or habit that is already routine (Clear, 2018).

For example, if a student is always late with a to-go cup in hand, perhaps they could stack the habit of arriving fifteen minutes early to get their morning coffee. Reflection is a key supplement to iteration. Consider starting each class with a warm up exercise that promotes reflection. Perhaps it is tied to current events, the assignment they are currently working on, habits they want to break, or future assignments.

As easy as habit stacking may sound, the antidote to stigma is not resilience. It’s advocacy. Anna Philip and I had the opportunity to brainstorm with Jason Wallin, Director of Upper School at Churchill School and Center. The Churchill School and Center is a private institution in Manhattan catered to support students with learning disabilities under IEPs. In working with students who have IEPs, and who later may seek out accommodations at the college level, he shared, “When students understand themselves, their motivations, and their behaviors, they are more likely to advocate for themselves” (J. Wallin, personal communication, June 2023).

I am thrilled to pivot from “stigmatization” to “advocacy.” How might we support students with accommodation letters in having the conversations with instructors? How might we support struggling students who do not have accommodation? How might we support instructors with available resources for students with accommodation?

Instructors at Pratt are encouraged to flag students in a workflow browser-based system called Starfish. This portal allows faculty to communicate with students about their classroom behaviors in a non-verbal yet authoritative manner. Various flags like “Well Being” and “Absence/Tardiness” are selected by faculty based on student behaviors. Each flag alerts the appropriate student services. That service sends an email to the student encouraging them to take advantage of on-campus services in response to an instructor’s flag.

Figure 9

Strategies and Practices for Student Success: Starfish and Beyond

Strategies and Practices for Student Success: Starfish and Beyond

Note: Sample Email Autogenerated to Starfish-Flagged Student

My colleague and collaborator, Anna Philip, was instrumental by sharing her personal anecdotes from the classroom: “I want faculty to have proper training and supportive tools for how to best address different learning needs in the classroom, like providing talking points, writing templates when using Starfish, and information about the federal disability act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act,” she said (A. Phillips, personal communication, November 16, 2023).

In my career change from project manager at CNN to full-time faculty, it seemed logical that incorporating current events into the practicum would be unique to my pedagogy. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, I wanted to use news media as a conduit for new learning experiences. I was woefully unprepared for what happened.

As a new teacher, I was aware that my written communication was stronger than my verbal, so I sent a weekly email to students outlining assignments for the next class. One of my students was Ukrainian and responded that he would not be attending class to be available for his family. I asked how I or the class could help. He responded that he was asking our department if he could post a donation box at the entrance of the building. I wrote the department contact he mentioned for clarity. Utilizing the fact that the student would not be present that week, I planned to foster a class discussion: “How can we help a member of our community?”

Some students confessed they were avoiding reports altogether in fear of misinformation. Others were very uncomfortable discussing the politics of sides. There was laughing while they tried to formulate their thoughts. I understand that laughter can be a coping mechanism for fear. I didn’t understand, however, that it is a lot to ask a student to question how they receive information. I felt it was my duty as an instructor of an international community to not ignore the closeness of war. I quite honestly forced it into the classroom as broadly and gently as I thought possible: by utilizing a rudimentary technique we just learned, a mood board of up to ten images, to relay the sentiment and feelings of an informational campaign.

We formulated the assignment together in class—uncomfortably, everyone agreed to develop either a) an awareness campaign or b) a fundraising campaign—and I typed up the guidelines and made them available to students by message board. "If anything, this will be an exercise in working with a subject matter or client that makes you uncomfortable," I said. "Please email me your questions and concerns." I received no questions or concerns.

The co-created guidelines directly influenced the strategy of the Ukrainian student; when it was his turn the following week, he shared shocking images of destruction and displaced refugees. When he became emotional, I immediately thanked the class for participating in the exercise and I was sorry for any pain it caused. “If anyone wanted to continue their campaigns, I'd be happy to guide them outside of class time. Please reach out.”

No one reached out. What was I thinking?! Why did I find it appropriate to use pain as a learning tool?

This experience clarified my role in the classroom. Facilitator or professor, whatever I want to call myself, I hold tremendous power. As a result of this experience, I jumped at the chance, when offered by Pratt’s Center for Teaching and Learning, to earn a professional certification in Trauma Informed Learning from the University of Florida. I am grateful for this student who inadvertently challenged my thinking as a global citizen and holistic teacher. Thank you!

Graduate students are six times more likely to experience moderate to severe anxiety and depression than the general population (Evans et al., 2018). Stressors that contribute to poor mental health specifically among graduate students include:

- High-pressure demands

- Work/life imbalance

- Economic insecurity

- Uncertainty about careers

- Authoritarian leadership style of mentors

The L/AC supports all students, regardless of their identified ability or level of study. Like the Writing Center, the L/AC provides services to help students perform their best, no matter their present level of performance. This is an integral part of “meeting students where they are at,” a form of pedagogy described by Tom Klinkowstein, Adjunct Professor of Communications Design (personal communication, July 2023). Klinkowstein has been a Pratt instructor for thirty-four years. He’s witnessed how changes in technology alter the process of design. Likewise, he’s seen the opportunities unearthed by changes in disability legislation and policy. “Care before you dare” is another staple of Klinowstein’s classroom strategy. First, meet the students at their level. Modify assignments so they are approachable to all learners. Treat confidence as a skill. Support first, then push them to take risks.

Klinowstein’s pedagogy supports what author and psychologist Carol Dweck (2006) calls the “growth mindset” (p. 5). Mindsets are your collection of thoughts and beliefs that shape your thought habits; they affect how you think, what you feel, and what you do. Mindsets impact how you make sense of everything: your environment, the people you choose to surround yourself with, your own behaviors and thoughts.

“For decades, I’ve been studying why some people succeed while people, who are equally talented, do not. And over the years I’ve discovered that people’s mindsets play a crucial role in this process” (Dweck, 2006, p. 32). The growth mindset is learning-centered and documented through a series of milestones from acknowledgment of the required skill to practice, failure, goal setting, and eventual mastery.

Goal setting is a form of advocacy. This can be part of the initial conversation. Ask the student what they already know and what new skills they want to learn. Throughout the semester, chunk studio assignments into manageable pieces. For example, consider one overall project broken into multiple parts. Allow multiple ways for students to demonstrate their learning and understanding.

In March 2022, in my third semester of teaching, Anna Philip and I were invited by CTL to lead a Zoom discussion open to all Pratt faculty. We knew we needed a partner and asked Anna Riquier, Associate Director for Accessibility, to be our guest. Titled Faculty Spotlight: Structuring Inclusive Classrooms to Support Diverse Learners, the intention was to teach the basic frameworks for cultivating inclusive classroom experiences for higher education art students. The goal was to help them build confidence to iterate and adjust to their student dynamic. The workshop explored the overarching principles to ensure that classrooms provide community, inclusion, and belonging. These include reframing, iteration, reflection, and adjusting how we share and receive information.

It sounds incredibly optimistic, but I hope conversations like these sparked action and collaboration. Throughout this process of investigation, I discovered new challenges, like the oversaturation of messaging and information. Rest affects performance. Encouraging risk is required when connecting to graduate students more so than undergraduate. Although eager to formulate a network of events and shareable digital teaching tools—I’ve always wanted to host a podcast!!!—I must respect the process of listening, observing, and building authentic relationships. The results of this effort are years in the making, and patience is required.

It Starts With a Clear Call to Action, Highly Visible to All Faculty: Require Integration of Student Engagement Techniques Within Studios and Classrooms

- In collaboration with the L/AC, we as faculty need to co-create a system of resources:

- Test, iterate, and distribute “Me as a Learner” Surveys all faculty may easily implement in their classrooms and begin the transformation of instructor as facilitator over leader.

- Create a digital and physical hub for immediate self-service faculty assistance. If this scenario happens, then do or try this.

Active Teaching Is in the Toolbox of Inclusive Pedagogy

Here are three very basic exercises you can incorporate into your classrooms this week:

Character Defines Your Teaching Framework

We learn by example. Fundamentally, our definitions of love, ability to prioritize, and ability to communicate our needs originate from childhood, where we mimicked our caregivers. Students are human and still participate in this framework of learning. Instructors must honor that they set the example of professionalism, in life and career, for students.

Get Involved With the CTL

You will be encouraged, challenged, and celebrated. You will complete certifications and read books on your time and their dime. You will build the support system you need to begin the journey of adapting inclusive pedagogy. Visit https://prattctl.com/.

Set Up Time With the L/AC

The best way to understand L/AC resources is to walk through them with a member of that office. If one of your students has an accommodation letter, reach out to the advisor listed in their letter to begin a discussion. It doesn’t have to be specific to the student: You can start here to get an overview of what the L/AC has to offer. Drop by the first floor of ISC Building near the corner of Hall and Willoughby. Email lac@pratt.edu to set up an appointment.

Inclusion in Your Syllabus

An easy introduction to inclusive pedagogy is to openly welcome students with learning disabilities on the first page of your syllabus. The quote below is an example from one author that you can copy into your syllabus:

“If you are disabled, I welcome a conversation to discuss your learning needs. I want to make sure you succeed in our course.” It’s simple but sends a big message: You welcome the presence of neurodivergent students; you welcome their disclosure; you are willing to collaborate to build an accessible classroom. Note that my suggested phrasing doesn’t mention ‘accommodations’ or ‘disability services’ or ‘requirements.’ You are telling your students that this conversation will not be about the bare minimum required by law, but about how to help them get the best education you can provide. (Pryal, 2023)

Using a collaborative adjective like “our” instead of “my” course is an easy way to practice inclusive pedagogy.

I am reminded of the most confidence-boosting event in my first year of teaching. Pirco Wolfframm, Acting Chairperson of Undergraduate Communications Design, invited me to Imploading Histories >> Teaching Forward, a two-part workshop in October 2022 and March 2023. I came to campus on a Saturday for free breakfast and to meet more peers/potential confidants. We sat together, mostly young, female faculty with very different backgrounds; we were mothers, immigrants, graduates of the program, new instructors from different institutions, artists, and practitioners. The only familiar face was Pirco, the facilitator. She began the conversation with a statement I’ll never forget: “You are here because you’ve shown the department you want to do things differently.” This forum she created was actionable support through thought-provoking conversations backed by collective, well-informed knowledge of a community, facilitated by someone I knew well and respected. I want to make my students feel just as Pirco made me feel: comfortable, seen, and heard. Colleagues from that workshop still greet me with big smiles and supportive questions beyond the “how are you?” pleasantries. I want to facilitate environments just as Pirco did: inclusive, welcoming, and supportive.

References

American Psychological Association (2003). Resilience. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. Jossey Bass.

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Avery.

Davidson, C., & C. Katopodis. (2022). The new college classroom. Harvard University Press.

Deaton, P. (June 2023). Accessible and inclusive learning experiences. Learning and Teaching Seminar. The University of Michigan College of Literature, Science and the Arts.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Publishing Group.

Eisenberg, D., Downs, M. F., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709335173

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus.

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Literacy Information and Communication System. (n.d.) Teaching excellence in Adult Literacy Center fact sheet no. 4: Metacognitive processes. https://lincs.ed.gov/state-resources/federal-initiatives/teal/guide/metacognitive

Moore, N., & Soliman, S. (2023, September 26). Faculty spotlight: Community building workshop [Zoom].

https://prattctl.com/2023/08/16/community-building-workshop-with-shireen-soliman-and-natalie-moore/

MIT OpenCourseWare. (2017, February 24). Think-pair-share [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqrOxeL-fwk&t=32s

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: The evidence for stigma change. The National Academies Press.

Peoples, L. Q., D’Andrea Martinez, P., Foster, L., & Martin, J. (2021). How to address educational equity: Research-based recommendations for educators. NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools. https://knowledgeworks.org/resources/address-educational-equity-research-recommendations/

Pryal, K. R. G. (2023, March 29). How to Teach Your (Many) Neurodivergent Students. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-teach-your-many-neurodivergent-students

Purdue University Wilmeth Active Learning Center. (2023). Active learning strategies. https://www.purdue.edu/activelearning/Need%20Help/alstrategies.php

Pratt Institute. (n.d.). Faculty Resources FAQ. Pratt Institute. https://www.pratt.edu/administrative-departments/student-affairs/learning-access-center/learning-access-center-faculty-resources/faculty-resources-faq/

Shpiro, H. (2023, September 25). Strategies and practices for student success: Starfish and beyond [Zoom].

Supporting graduate student mental health and well-being. (2022). Council of Graduate Schools and the Jed Foundation.

University of Michigan College of Literature, Science and the Arts. (2022). Practical steps for inclusive teaching. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/inclusive-teaching/practical-steps-for-inclusive-teaching/

Here are three very basic exercises you can incorporate into your classrooms this week:

- Think/Pair/Share: This involves, first, independent reflection, then testing that independent rationale in pairs. As the facilitator, walk around the room and listen for misconceptions in this middle phase. Gently interrupt to mitigate the reinforcement of misconceptions. Conclude with a full-class discussion so learning expands to the group (MIT, 2017).

- Co-Learning: Assign research questions to individual students or pairs and provide initial resources for discovery. Invite them to explore the question further and require them to share a short presentation of their learning. Consider the context of the material when deciding whether to provide a rubric and deliverable outline or to leave the results completely open-ended. The result is a series of presentations, led by enthusiasts and absorbed as an ecosystem of learners. Consider spreading this out throughout the semester or devoting a single class as a symposium of co-learning (Purdue University, 2023).

- Muddiest Point: Prompt an open-ended poll for students to independently share where in the process they lack confidence. Consider asking: “What is the muddiest point in ___?” Process the responses together by grouping common themes. Address those common themes to the entire class (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

Character Defines Your Teaching Framework

We learn by example. Fundamentally, our definitions of love, ability to prioritize, and ability to communicate our needs originate from childhood, where we mimicked our caregivers. Students are human and still participate in this framework of learning. Instructors must honor that they set the example of professionalism, in life and career, for students.

- Support appropriate work/life balance. Answer or send emails only on weekdays from 9 to 5 p.m. Nothing is so urgent that it can’t wait. Students have many other priorities besides your class, and when you respect that by limiting correspondence during school hours, you set the example that you expect the same respect. Gmail has a great feature called “Schedule Send,” where you can write the email but schedule it to send later.

- Structure small group time. Collaboration is a key metric of career success. Group work can be new to students. Structuring what collaborative time looks like will help jumpstart their process. Perhaps you divide the class into groups of three. Require them to have a discussion to complete a simple deliverable with multiple steps. Prompt that deliverable and time box it, meaning outline the number of minutes they have to complete the assignment. For example, define and assign roles based on individual strengths and weaknesses. This multi-layered approach supports metacognitive skills through problem solving, time management, and interpersonal interactions.

- Up the encouragement. Critique is a required methodology of education and some students are culturally unfamiliar with this structure. You, as instructor, are wise and experienced, but the student has a perspective that you do not. Critique is not top-down speech. Consider it a discussion. Start and end this process with positive feedback. Always end critique with encouraging phrases like, “I look forward to seeing your next iteration,” or “you are very strong at interpreting collective feedback.”

- Reflection. Teach students that reflection is a key step in producing complex work. Perhaps you require a written reflection as part of weekly assignments. Create prompts to guide these reflections. For example: What specific design project(s)—from this class, others, or your own personal research—have informed your own practice and why? Encourage other forms of documentation like audio or sketches. Revisit these reflections throughout the semester and ask students to verbalize where reflection affected their end result.

- 1:1 conversations, on Zoom or in person. These can be hard to do for new teachers, but the benefits are outstanding. By showing students that you make mistakes too, you allow them to participate equally in the discussion of education. Although your voice may be louder in the classroom because of social hierarchy, their voice matters too.

Get Involved With the CTL

You will be encouraged, challenged, and celebrated. You will complete certifications and read books on your time and their dime. You will build the support system you need to begin the journey of adapting inclusive pedagogy. Visit https://prattctl.com/.

Set Up Time With the L/AC

The best way to understand L/AC resources is to walk through them with a member of that office. If one of your students has an accommodation letter, reach out to the advisor listed in their letter to begin a discussion. It doesn’t have to be specific to the student: You can start here to get an overview of what the L/AC has to offer. Drop by the first floor of ISC Building near the corner of Hall and Willoughby. Email lac@pratt.edu to set up an appointment.

Inclusion in Your Syllabus

An easy introduction to inclusive pedagogy is to openly welcome students with learning disabilities on the first page of your syllabus. The quote below is an example from one author that you can copy into your syllabus:

“If you are disabled, I welcome a conversation to discuss your learning needs. I want to make sure you succeed in our course.” It’s simple but sends a big message: You welcome the presence of neurodivergent students; you welcome their disclosure; you are willing to collaborate to build an accessible classroom. Note that my suggested phrasing doesn’t mention ‘accommodations’ or ‘disability services’ or ‘requirements.’ You are telling your students that this conversation will not be about the bare minimum required by law, but about how to help them get the best education you can provide. (Pryal, 2023)

Using a collaborative adjective like “our” instead of “my” course is an easy way to practice inclusive pedagogy.

I am reminded of the most confidence-boosting event in my first year of teaching. Pirco Wolfframm, Acting Chairperson of Undergraduate Communications Design, invited me to Imploading Histories >> Teaching Forward, a two-part workshop in October 2022 and March 2023. I came to campus on a Saturday for free breakfast and to meet more peers/potential confidants. We sat together, mostly young, female faculty with very different backgrounds; we were mothers, immigrants, graduates of the program, new instructors from different institutions, artists, and practitioners. The only familiar face was Pirco, the facilitator. She began the conversation with a statement I’ll never forget: “You are here because you’ve shown the department you want to do things differently.” This forum she created was actionable support through thought-provoking conversations backed by collective, well-informed knowledge of a community, facilitated by someone I knew well and respected. I want to make my students feel just as Pirco made me feel: comfortable, seen, and heard. Colleagues from that workshop still greet me with big smiles and supportive questions beyond the “how are you?” pleasantries. I want to facilitate environments just as Pirco did: inclusive, welcoming, and supportive.

References

American Psychological Association (2003). Resilience. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. Jossey Bass.

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Avery.

Davidson, C., & C. Katopodis. (2022). The new college classroom. Harvard University Press.

Deaton, P. (June 2023). Accessible and inclusive learning experiences. Learning and Teaching Seminar. The University of Michigan College of Literature, Science and the Arts.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Publishing Group.

Eisenberg, D., Downs, M. F., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709335173

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus.

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Literacy Information and Communication System. (n.d.) Teaching excellence in Adult Literacy Center fact sheet no. 4: Metacognitive processes. https://lincs.ed.gov/state-resources/federal-initiatives/teal/guide/metacognitive

Moore, N., & Soliman, S. (2023, September 26). Faculty spotlight: Community building workshop [Zoom].

https://prattctl.com/2023/08/16/community-building-workshop-with-shireen-soliman-and-natalie-moore/

MIT OpenCourseWare. (2017, February 24). Think-pair-share [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqrOxeL-fwk&t=32s

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: The evidence for stigma change. The National Academies Press.

Peoples, L. Q., D’Andrea Martinez, P., Foster, L., & Martin, J. (2021). How to address educational equity: Research-based recommendations for educators. NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools. https://knowledgeworks.org/resources/address-educational-equity-research-recommendations/

Pryal, K. R. G. (2023, March 29). How to Teach Your (Many) Neurodivergent Students. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-teach-your-many-neurodivergent-students

Purdue University Wilmeth Active Learning Center. (2023). Active learning strategies. https://www.purdue.edu/activelearning/Need%20Help/alstrategies.php

Pratt Institute. (n.d.). Faculty Resources FAQ. Pratt Institute. https://www.pratt.edu/administrative-departments/student-affairs/learning-access-center/learning-access-center-faculty-resources/faculty-resources-faq/

Shpiro, H. (2023, September 25). Strategies and practices for student success: Starfish and beyond [Zoom].

Supporting graduate student mental health and well-being. (2022). Council of Graduate Schools and the Jed Foundation.

University of Michigan College of Literature, Science and the Arts. (2022). Practical steps for inclusive teaching. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/inclusive-teaching/practical-steps-for-inclusive-teaching/