As educators, we have all experienced the need for more support and resources to foster community in higher ed design studios, both for ourselves and, in turn, our students.

Three professors—Shireen Soliman, Caroline Matthews, and Natalie Moore—came together through the CTL’s 2022–23 Faculty Learning Community to work collaboratively to explore how best to support faculty and students, with a focus on group projects and cultivating an inclusive classroom environment.

By coming together and forming our own community, we benefited from this valuable mentor circle, supporting and learning from one another while exchanging and compiling resources. We learned more about each other during our monthly meetings and came to leverage each other’s strengths: Caroline for summarizing and organizing our notes into something cohesive and readable, Shireen for her wizardry with a variety of visual tools, and Natalie for her knowledge of assessment and resources. We coalesced around a collective research goal: to provide faculty with overarching principles to ensure classrooms foster community, inclusion, and belonging.

These meetings also offered a time to connect with each other as humans and share our successes and setbacks, modeling the empathy and care we are aiming for in our classrooms.

During the spring semester of 2023, Caroline moved to her own work within the FLC. This article will outline the work we, Natalie and Shireen, explored together. You will find interventions, strategies, and theory-based practices that we implemented in our classrooms. We hope you will find these resources and insights valuable for your own communities of learning.

Natalie’s Work

The FLC goal that I set for my classroom was to introduce several strategies to create trust, build community, and guide feedback in order for students to be able to give reflective feedback to each other during class critiques. My approach to critique was guided by Critical Response Process (Lerman & Borstel, 2003) and alternative critique strategies borrowed from colleagues at Pratt and other schools.

In order to center the class and focus in, the class sessions were started with mindfulness exercises. These included:

Three professors—Shireen Soliman, Caroline Matthews, and Natalie Moore—came together through the CTL’s 2022–23 Faculty Learning Community to work collaboratively to explore how best to support faculty and students, with a focus on group projects and cultivating an inclusive classroom environment.

By coming together and forming our own community, we benefited from this valuable mentor circle, supporting and learning from one another while exchanging and compiling resources. We learned more about each other during our monthly meetings and came to leverage each other’s strengths: Caroline for summarizing and organizing our notes into something cohesive and readable, Shireen for her wizardry with a variety of visual tools, and Natalie for her knowledge of assessment and resources. We coalesced around a collective research goal: to provide faculty with overarching principles to ensure classrooms foster community, inclusion, and belonging.

These meetings also offered a time to connect with each other as humans and share our successes and setbacks, modeling the empathy and care we are aiming for in our classrooms.

During the spring semester of 2023, Caroline moved to her own work within the FLC. This article will outline the work we, Natalie and Shireen, explored together. You will find interventions, strategies, and theory-based practices that we implemented in our classrooms. We hope you will find these resources and insights valuable for your own communities of learning.

Natalie’s Work

The FLC goal that I set for my classroom was to introduce several strategies to create trust, build community, and guide feedback in order for students to be able to give reflective feedback to each other during class critiques. My approach to critique was guided by Critical Response Process (Lerman & Borstel, 2003) and alternative critique strategies borrowed from colleagues at Pratt and other schools.

In order to center the class and focus in, the class sessions were started with mindfulness exercises. These included:

- stream of consciousness writing—start the class with 5 minutes of automatic writing;

- three good things and why—adapted from Flourish (Seligman, 2011);

- Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies writing prompt—use to jump start automatic writing;

- screening John Cage’s 4’33”—reflect on “silence”;

- reflective journal—How does it feel to be ¾ done with your first year of college?;

- S.T.O.P. (Stop, Take a breath, Observe, Proceed)—a mindfulness technique for stress reduction;

- plant journal—document weekly growth of plant during the semester (students will use documentation as a prompt for final assignment about time and growth);

- use a storytelling card from The Moth—students tell each other stories moth style, refine in small groups, and develop a storyboard for a film or animation;

- use an excerpt from T. S. Eliot’s (1943) poem “Little Gidding” (which was also featured as a title card in the film Run, Lola, Run)—reflect on the meaning of the poem from a personal point of view on how it relates to the film:

We shall not cease from exploration / and the end of all our exploring / will be to arrive where we started / and know the place for the first time.

- reflect upon teamwork and whether it pulled out any strengths in you that you were not aware of previously.

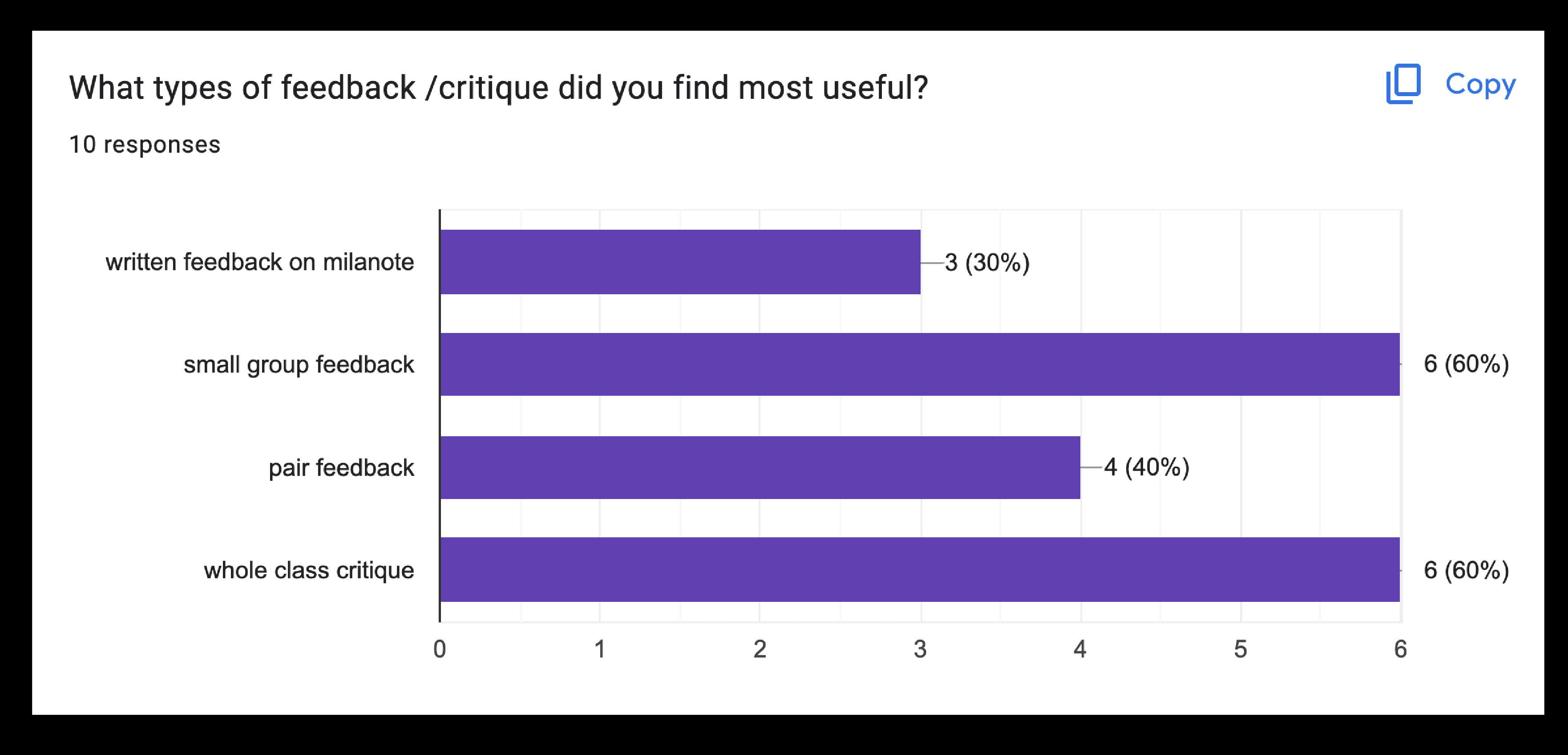

Of these warm-ups, students felt the stream of consciousness writing was the most helpful, as evidenced by the data and responses gathered through a survey given at the end of the semester.

Figure 1

End of Semester Survey Responses

End of Semester Survey Responses

As these students reported:

- “I think the ones that were most helpful for me were the more meditative exercises. I thought it was helpful/refreshing sometimes to take a moment to break before class starts, since jumping right into work can be overwhelming at times.”

- “It was peaceful and very helpful to know my thoughts.”

Although it was interesting to try different types of mindfulness warm-up exercises over the course of the semester, I realized that it was more helpful to stay with a routine of the stream of consciousness writing. The first year of college can be overwhelming and stressful, with many assignments happening concurrently. The simplicity and practice of one centering exercise seems to be more useful than adding even more new knowledge to the student’s workload.

The course assignments and feedback sessions were also planned with the intention of building trust within the class community and an openness to try new approaches to materials and processes. This was done by balancing individual assignments, reflections on a shared Milanote board, small group feedback sessions, and group projects.

Because students are often reluctant to engage in group assignments, I tried to structure the group aspect as teamwork with a component of the assignment to be completed individually. With this structure, I hoped to avoid the inequities of effort that make group assignments challenging while still building community, collaboration, and trust within the groups. The two assignments where I employed this structure were a multi-cam video assignment, which necessitated a group for the shooting and acting but was edited individually, and a sound design assignment where students worked in groups to create the soundtrack and then created their own individual animations to accompany the sound. I will elaborate here a bit more on the sound design assignment. The kick-off was a field trip to the artist/musician/educator Ken Butler's studio in Williamsburg. Butler generously showed the many instruments he has created over the years with scavenged material and explained to students how they could create their own instruments.

Figure 2

Studio Visit With Ken Butler, Demo Playing of a Constructed Instrument

Studio Visit With Ken Butler, Demo Playing of a Constructed Instrument

Figure 3

Ken Butler Explaining How to Create a Simple Instrument

Figure 4

“Band 3,” Carly Young, Nighla Chen, Hannah Wong Nakata, Performing

“Band 3,” Carly Young, Nighla Chen, Hannah Wong Nakata, Performing

After the visit to Ken Butler’s studio, students were grouped into “bands” of three-to-four students. Each group came up with a concept for their musical score and worked together to design and create instruments that would work together to create the types of sounds that they were interested in. For example, the group pictured in figure 4, “band 3,” decided they wanted to create sounds emulating nature and a soundtrack that would feel calming. Carly Young, on the left, made a paper wind chime that sounded like rustling leaves when moved. Nighla Chen, center, used wine glasses ranging from nearly empty to full of water to create a melody with the different pitches produced by tapping on the glasses. Hannah Wong Nakata, right, filled a paper tube with rice that created the sound of rain. They recorded a few takes of playing their instruments together until the recording could be used as a soundtrack for their individual animations.

Figure 5

Animation With Soundtrack From “Band 1,” Sofia Moreno Lima

Animation With Soundtrack From “Band 1,” Sofia Moreno Lima

After recording sessions with the class “bands,” each student then used their session recording as a soundtrack for a motion graphics animation. In this example by Sofia Moreno Lima (figure 5), a graphic notation was created in time to the soundtrack. This balance of individual and group collaboration enabled students to have freedom with their personal projects while benefiting from the community and feedback garnered from working together.

In a similar fashion, I began to structure critiques in a different manner. The most successful were small group feedback sessions, of two-to-three students, at the draft or prototyping stage, followed by entire class critiques for the final result. The intimate feedback sessions gave students further insights into the process and thinking behind their peers’ work and helped to direct feedback with the entire class during the larger critique sessions. In both the full- and small-group critiques, one student was tasked with taking notes for the presenter. This helped students remember what was said during the critique session when many are nervous and focused on their own presentation and thus have a hard time remembering what was said.

I borrowed heavily from Critical Response Process (Lerman & Borstel, 2003) and its approach to garnering helpful feedback and dialogue about a piece of work. Although Lerman & Borstel wrote the book for dancers, I find the ideas translate well into critiques of visual work.

The basic idea is outlined below:

The Process

The Critical Response Process takes place after a presentation of artistic work. Work can be short or long, large or small, and at any stage in its development.

The Core Steps

- STATEMENTS OF MEANING: Responders state what was meaningful, evocative, interesting, exciting, or striking in the work they have just witnessed.

- ARTIST AS QUESTIONER: The artist asks questions about the work. After each question, the responders answer. Responders may express opinions if they are in direct response to the question asked and do not contain suggestions for changes.

- NEUTRAL QUESTIONS: Responders ask neutral questions about the work. The artist responds. Questions are neutral when they do not have an opinion couched in them. For example, if you are discussing the lighting of a scene, “Why was it so dark?” is not a neutral question. “What ideas guided your choices about lighting?” is.

- OPINION TIME: Responders state opinions, subject to permission from the artist. The usual form is “I have an opinion about ______, would you like to hear it?” The artist has the option to say no. (Lerman & Borstel, 2003)

The most useful concept outlined in the book is the second in the list above, which empowers the student who is presenting work to ask what they want feedback on specifically. This allows the student to take ownership of their critique and get concrete constructive feedback on the elements that they need help with. I also found Step 3, Neutral Questions, quite helpful in avoiding opinions about a work that do not consider the student's intent.

Figure 6

Forming Neutral Questions, From Lerman & Borstel (2003)

Although the survey responses indicate that small-group feedback and whole-class critique are equally valuable, in reading the comments, students mentioned appreciating the value of the small-group or pair formative feedback session with notes that they could work from. The whole-class critique was set up as a screening, where everyone could see each other’s work, which they really enjoyed. In the future I will employ both—small-group or pair feedback for works in progress followed by full-class screening. When I used that structure, I did feel that the students had enough trust and knowledge of others’ work from the small-group sessions that they could give more meaningful feedback during the larger class screenings/critiques:

- “I think pair feedback was unique compared to the kind of critique done in our other foundation classes, and it’s nice to switch it up from the usual class critiques, which get drawn out at times.”

- “I think small-group critique is most helpful, especially for the suggestions like how to make better.”

- “I think the smaller groups writing their critiques on paper worked the best. Sometimes people are nervous to give critiques to their classmates, so I think it was nice to look back on the notes they gave.”

Figure 7

End of Semester Feedback Survey

End of Semester Feedback Survey

Was I able to build community and trust in this class that enabled students to give more reflective and helpful feedback during critique? Sometimes. I cannot say these strategies were 100% effective, but many of them were quite helpful in forming community, trust, and an openness to new ideas and ways of working. I will continue to employ a few of the strategies that I have mentioned in this overview: stream of consciousness free-writing to center the class at the warm-up, assignments that incorporate components of teamwork paired with individual work, and in-process feedback sessions before the whole class critique. These are the ones that had the clearest benefits in my observations, conversations with students, and replies in feedback surveys. I also feel that providing structure that empowers the student presenter in the larger critiques was enormously helpful, as was the addition of the note-taker role.

Shireen’s Work

In virtually all spaces in academia that I inhabit, I am “the only one.” I am a multi-hyphenate: Arab-American, Muslim-American, Fashion Designer, Consultant- and Freelancer-turned-Professor (would-be academic), Community Leader, Teaching Artist, and more. As such, and as is so often the case for adjuncts in higher education, I am very often searching for / yearning for spaces, dynamics, and groups that “feel” like “community” to offset the "aloneness."

During the Pandemic Academic Years of 2020–21 and 2021–22, and even into 2022–23, my ongoing search for community became all the more urgent as we educators and students experienced physical as well as social isolation during this time of crisis.

It was, in fact, in the Spring of 2022 when an article that caught my eye, “Building Community in Times of Crisis,” caused me to reflect on the following questions: How could the lessons of the Pandemic, and specifically our strategies rooted in Trauma Informed Pedagogy, continue to be mindfully applied moving forward in order to foster a sense of community among faculty and, in turn, students? I also wondered: What constitutes a “crisis”? How do we know when we’re “out of crisis”? Does the state of being “not in crisis” even exist in higher ed? And technically: Does the question regarding “crisis” even matter? Doesn’t the longing for community and connection exist despite, or due to, external events?

This is the key paragraph that ultimately led me to my research question for the FLC during AY 2023–24:

When university leaders approach organizational communication simply as a matter of distributing unilateral email announcements, the recipients generally feel disempowered and isolated. In contrast, when administrators set up multilateral exchange dynamics that explicitly acknowledge, enable, and invite engagement, bonds can begin to form and the communication system can even begin to sustain itself. In organizational theory this dynamic is termed “the paradox of power,” where the average manager sees sharing power as a “loss,” and the wise leader recognizes there is much more to be gained in vibrant synergy than is ever possible in a rigid structure [emphasis added]. Over-control weakens systems and reduces their ability to deal with challenges. As Wilmot and Hocker (2012) explain, “Equity in power reduces violence and enables all participants to continue working for the good of all parties, even in conflict.” (Radwan, 2022, p. 371)

Thus, my initial research questions were:

These questions soon led me to consider a particular area of design education often fraught with tension, confusion, and even dread: the design studio group project.

Thus, I arrived at my FLC Research Quandary and questions:

- How could the strategies that worked so well for the administration-faculty dynamic during the pandemic be adapted and applied to the faculty-student dynamic going forward?

- How could I apply these ideas and practices in my own design studio classrooms and projects?

These questions soon led me to consider a particular area of design education often fraught with tension, confusion, and even dread: the design studio group project.

Thus, I arrived at my FLC Research Quandary and questions:

- What are the obstacles to a student experiencing a "positive group project dynamic" in the higher ed design studio?

- How can actively cultivating a culture of inclusion through a sense of community result in the shifting of the perception of the “dreaded group project” to an experience of parallel play leading to: more experimentation, more sense of ownership, more long-lasting benefits through peer engagement/learning/bonding?

While we see challenges around equity, access, and personal/academic imbalances in group dynamics and learning across many (if not most) higher ed classrooms, the challenges of the higher education design studio are unique. In the design studio space, beyond the issues above, there are very distinct creative and technical abilities that impact arriving at a unified, cohesive aesthetic and design voice/language. The wide range of approaches, philosophies, and visual/conceptual directions must be navigated with sensitivity to each designer and their identity. Such exploration and decisions require distinct strategies and awareness to allow all group members to feel seen, safe, and willing to experiment.

As my focus is on group projects in the Fashion Design studio, I turned to a book by my esteemed Parsons colleague Steven Faerm, Introduction to Design Education: Theory, Research, and Practical Applications for Educators, for theoretical guidance and principles. Through my engagement with this text, I encountered several key ideas related to my research questions.

Key Idea 1

Design students’ sense of inclusion is especially vital to their creativity and abilities to innovate design:

Key Idea 2

Students, in their design classrooms and within the broader school culture, must feel a sense of belonging if they are to engage fully in learning experiences:

Key Idea 3

Ensure positive group dynamics.

When facilitating collaborative learning, we must give concerted attention to group dynamics: if a group is dominated by more assertive students, particularly ones whose behavior may exclude others from full participation, we must intervene to guarantee we receive feedback from all students. This will ensure a sense of inclusion and of belonging throughout the complete class (Faerm, 2023, p. 247).

Key Idea 4

Cultivate relationships and community.

Creating moments to personally connect with each student and resultantly strengthen a sense of community among our students is a core technique for supporting students’ feelings of belonging and inclusion. Simple acts like asking students what they hope to gain from the course, how they’re doing in their other courses, and what hobbies or extracurricular interests they have will demonstrate your care and genuine concern for them. These practices also allow you to see students as individuals who possess distinct backgrounds, needs, goals, and learning styles. This is critical information you need in order to shape your teaching to be centered on inclusivity—and the importance of the individual—as opposed to exclusivity or bias (Faerm, 2023, p. 249).

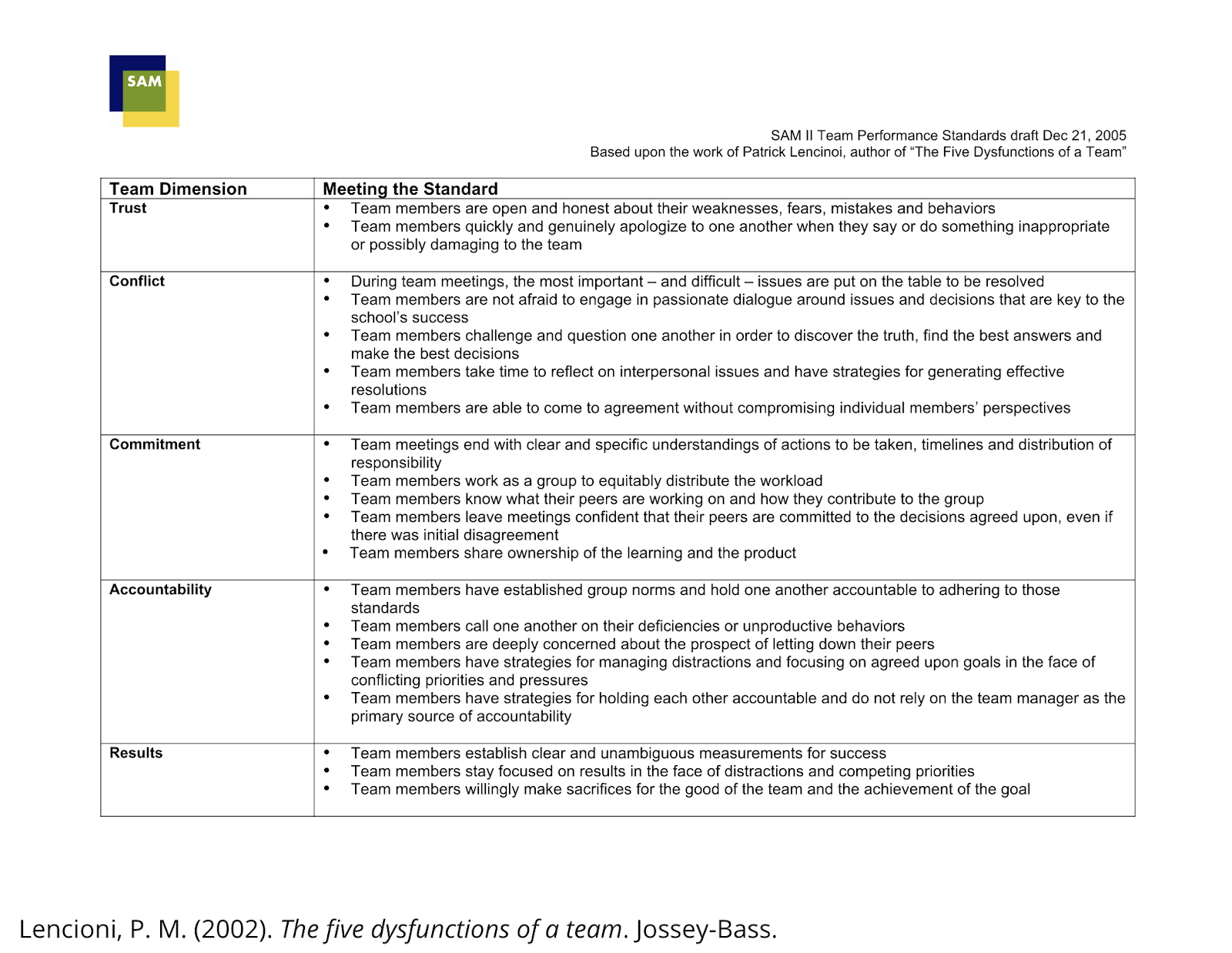

Additionally, the SAM II Team Performance Standards table in Figure 8 offered valuable insights more broadly on group dynamics and the conditions for positive and thriving groups as “communities.”

Figure 8

SAM II Team Performance Standards Table, From Lencioni (2002)

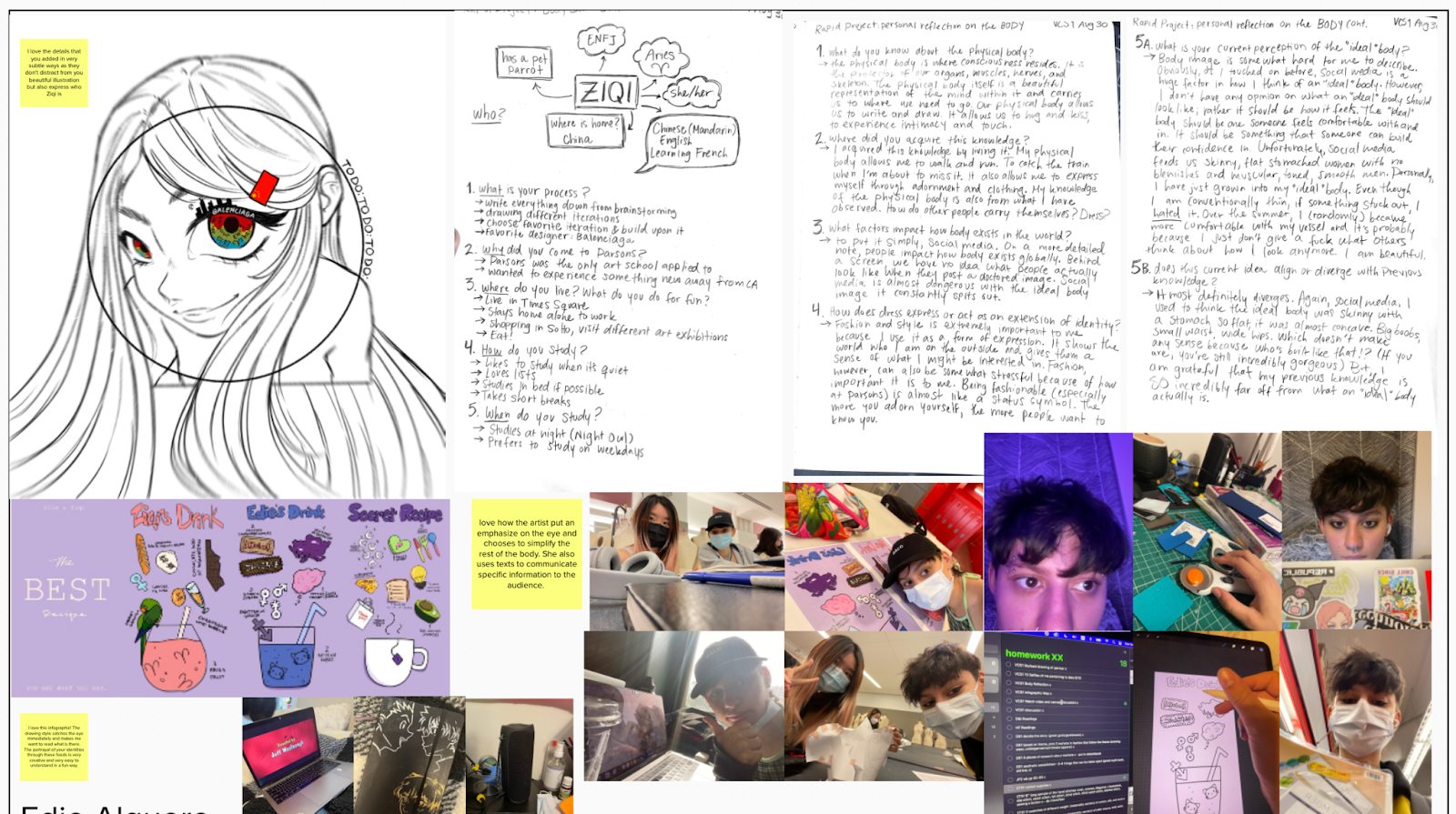

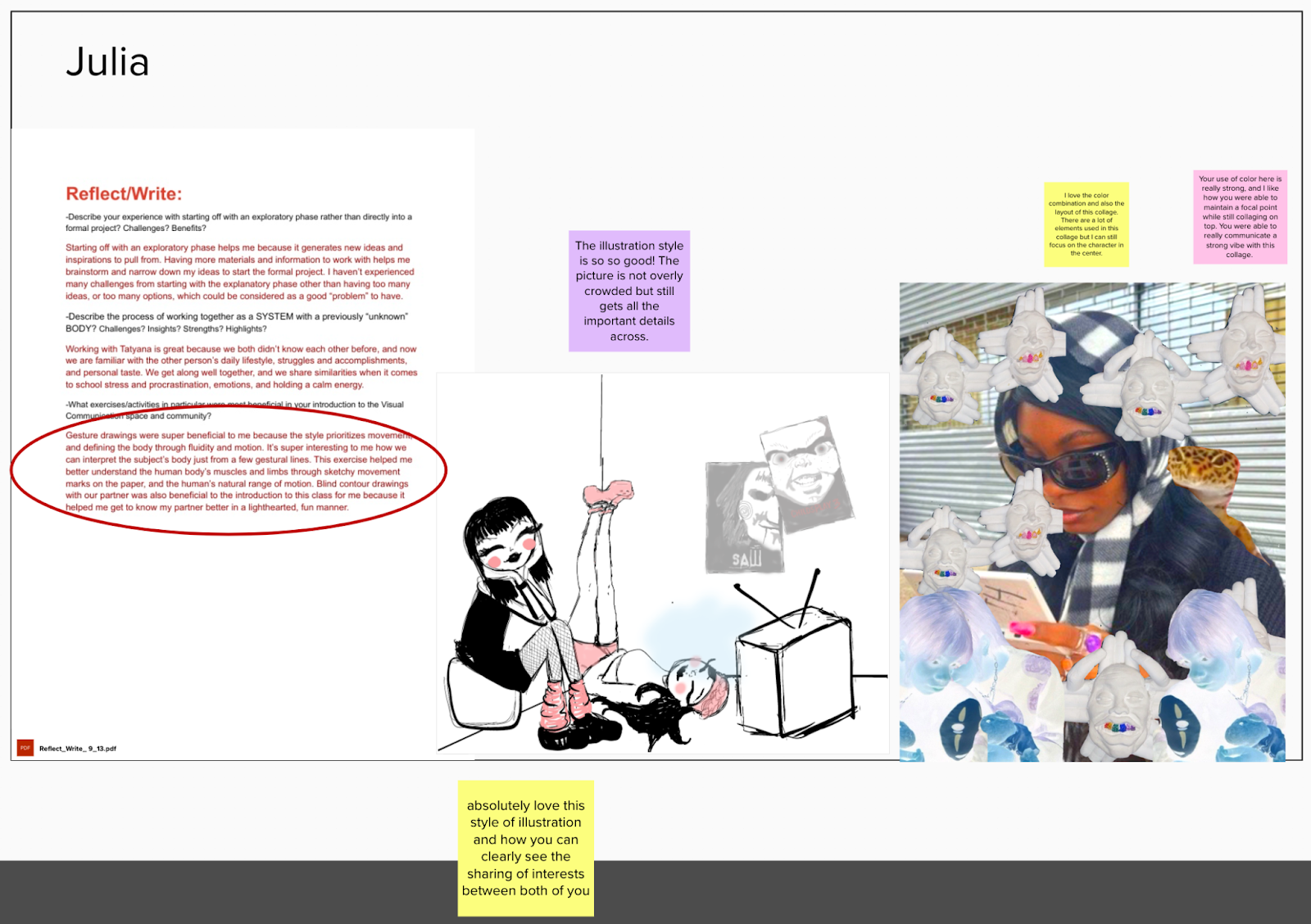

Students create content based on interviews and research of their partner/system. They are then tasked to create images/illustrations and infographics to visually communicate the gathered data and process.

Figure 10

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Showing the Final Assignment of the Two-Week “Partner Project”

Students co-create content based on their emerging knowledge and experience of their partner/system. They are then asked to submit a written reflection (from prompts provided by me) on the experience of beginning the semester with a “no grade” Orientation Partner Project.

This experience, while presented as an orientation, also serves the socio-emotional needs of the students by establishing a culture of community through a sense of security, accountability, and safety. Students expressed in their reflections afterward that, while they were, at first, trepidacious about partnering with a stranger, they concluded by having found a friend and partner with whom to embark on the journey of the course experience.

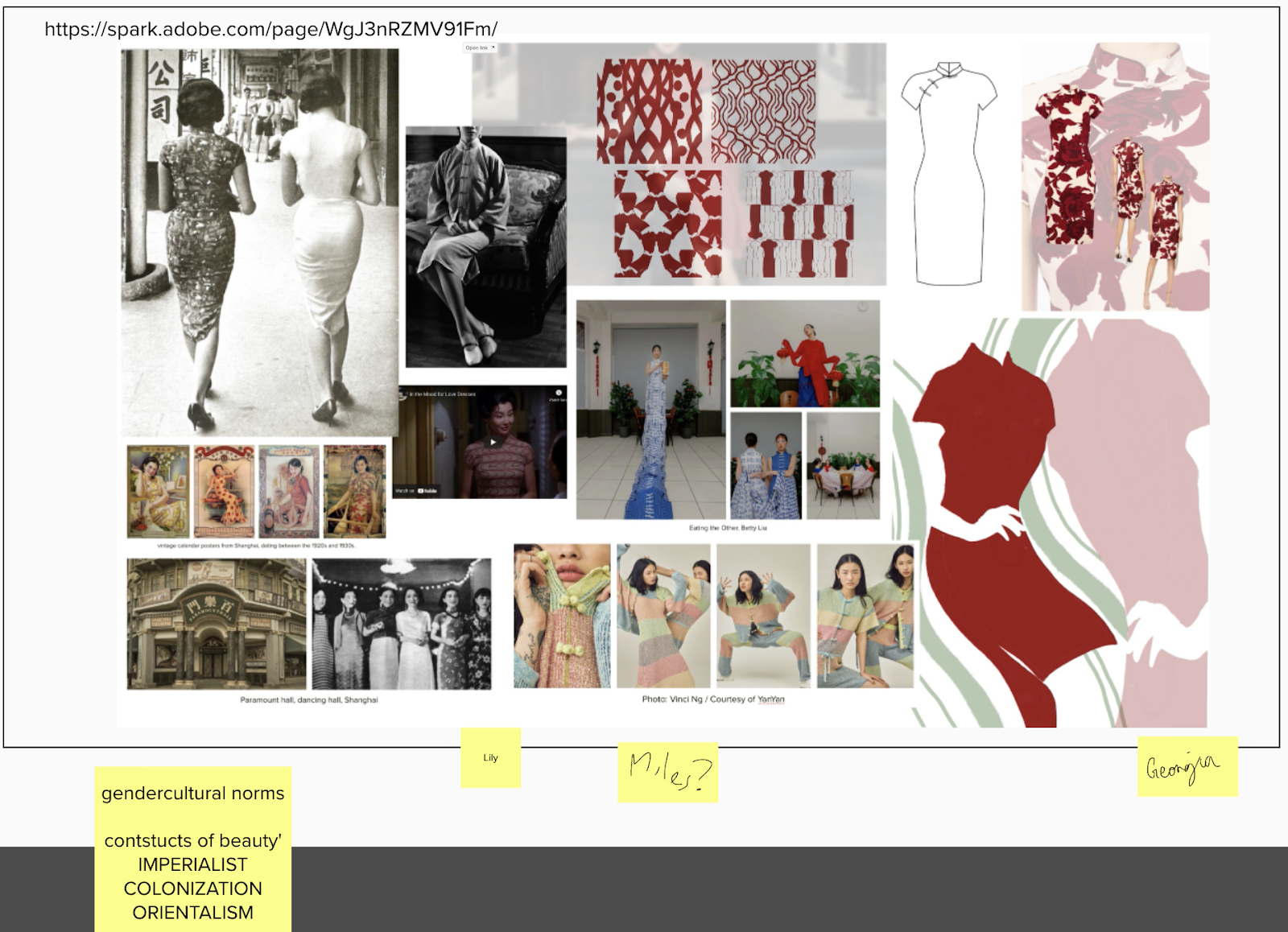

Case Study 2: End of Semester “Design Collective” (Fall 2021).

Semester Theme: THE BODY (and Fashion)

First step: Students each do their own research on possible topics around Body and Fashion, affirm their own area of curiosity, and connect with their own “WHY.” Examples of topics included: anti-Asian hate and racism through fashion, class and exclusion through fashion, body positivity and racism, etc.

Second step: Once they identify a topic and articulate why it MATTERS through their research and first draft proposal, they arrive at the “shop-around activity.” In this whole-group class activity, students hear each other’s presentations of topic research and areas of interest and “shop around,” seeking to align with like-minded proposals and come together to support the work of creating an immersive project to visually communicate their point of view and vision for the future of this topic through the lens of fashion.

Third step: Once grouped together, the group members will work to re-examine and re-affirm common goals/objectives/message based on the tasks/deliverables of the project brief. The group then works toward creating the suite of elements needed for the ultimate collective experience.

Students present their chosen topic during the “shop-around activity,” while fellow students place post-its of the overarching themes that they feel are being expressed.

The week after the “shop around,” students present additional research and ideation. Students then “sign up” to be considered for various groups that also align with the shared themes of their chosen topics. Ultimately, the groups are self-selected or selected with a bit of logistical support from me.

The culture of community that’s been formed by the end of the semester has already provided students with a sense of safety and belonging. By shifting the agency of choosing how the groups are formed, students are embarking on the group’s creative journey already feeling a sense of belonging and shared values and interests.

Forming Our Own Community as Educators to Educators (to Students!)

During this mid-year presentation, we researchers, as a cohort, expressed overlapping explorations and interests. True to my brand, as a perpetual seeker of community, I put out a call for like-minded peers who would be willing to work together on the theme of community in our own supportive network. Natalie and Caroline, who were also exploring the creation of systems of supports for educators and students from different lenses, answered the call, and we forged our community of accountability, shared labor, shared talents, and, above all, spaces of shared empathy and respect.

Finding connections across our research, we decided to not only share our work in the classroom with our students, but also to create a resource that fellow faculty could try in their own classrooms. We met biweekly and identified the overlaps and shared core ideas of our mutual research.

While Caroline remained with us for the planning phase and the valuable solidarity, she joined another FLC partner to complete work on a similar research project. Our meetings began by discussing what we were doing in our own classrooms, our successes and stumbling blocks, and sharing ideas of how to improve community, equity, and support. We created lists to share and learn from each other. Finding this resource helpful, we reached out to the CTL to propose a workshop modeled on sharing and building upon these strategies.

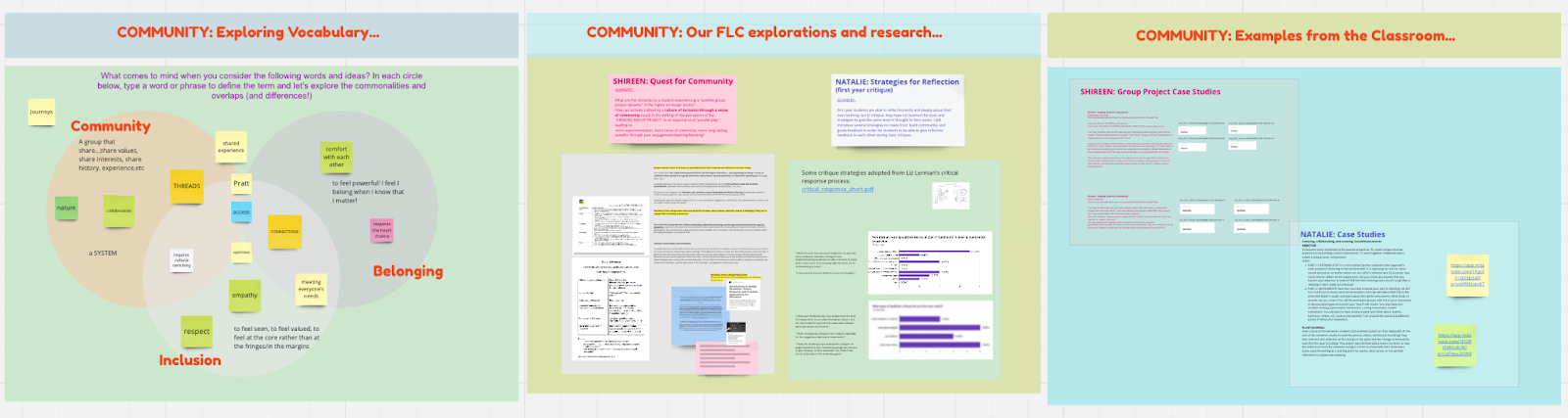

Below is the description and visual documentation of our workshop:

Workshop Proposal: Community, Inclusion, and Belonging in the Classroom

AUDIENCE: College-level educators in fine arts and design who require group work.

GOAL: Share strategies and practices to ensure classrooms provide community, inclusion, and belonging; this includes reframing, iteration, reflection, and adjusting how we share and receive information.

ONE-SENTENCE DESCRIPTION: Exchange basic frameworks and best practices for cultivating inclusive classroom experiences for higher education art students; build confidence to iterate and adjust to your student dynamic with support of fellow educators.

Figure 13 is a screenshot from the Miro board designed for the interactive workshop held on September 26, 2023. Offered as a Faculty Spotlight through the CTL, the workshop was promoted to Pratt faculty across disciplines. We offered spaces for conversation, resources, and case studies of key ideas and practical strategies for the higher ed classroom to fellow educators and “community seekers.”

From our experience in the FLC, it became evident that the need for communities and support for both faculty and students remains resonant. We created activities for educators to consider and share vocabulary, experiences, and practices, all rooted in theory and research. These strategies and considerations around mindfulness, empathy, trust, and connection are only a starting point. The “quest for community” is ongoing and we invite you to join us and embark on this journey together.From our experience in the FLC, it became evident that the need for communities and support for both faculty and students remains resonant. We created activities for educators to consider and share vocabulary, experiences, and practices, all rooted in theory and research. These strategies and considerations around mindfulness, empathy, trust, and connection are only a starting point. The “quest for community” is ongoing and we invite you to join us and embark on this journey together.

References

Eliot, T. S. (1943.) Little Gidding. Four quartets. Gardners Books.

Faerm, S. (2023). Introduction to design education: Theory, research, and practical applications for educators. Routledge.

Lencioni, P. M. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team. Jossey-Bass.

Lerman, L., & Borstel, J. (2003). Liz Lerman's critical response process: A method for getting useful feedback on anything you make from dance to dessert. Liz Lerman Dance Exchange.

McAleer Balkun, M., & Radwan, J. (2022, May 2). Building community in times of crisis. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/academic-leadership/building-community-in-times-of-crisis/.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

As my focus is on group projects in the Fashion Design studio, I turned to a book by my esteemed Parsons colleague Steven Faerm, Introduction to Design Education: Theory, Research, and Practical Applications for Educators, for theoretical guidance and principles. Through my engagement with this text, I encountered several key ideas related to my research questions.

Key Idea 1

Design students’ sense of inclusion is especially vital to their creativity and abilities to innovate design:

- One study noted “the single most important factor contributing to innovation ... was ‘psychological safety,’ a sense of confidence that members of a group will not be embarrassed, rejected, punished, or ridiculed for speaking up” (Tavanger, 2017, as cited in Faerm, 2023, p. 243).

- “Adopting [a community-centered] approach enables design schools to raise the levels of engagement, authenticity, and respect between students and among the student body and faculty” (Faerm, 2023, p. 243).

Key Idea 2

Students, in their design classrooms and within the broader school culture, must feel a sense of belonging if they are to engage fully in learning experiences:

- “As design educators, if we are to support students’ holistic development, we must first cultivate a safe and inclusive environment” (Harvard University Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning [HUBC], n.d., n.p., as cited in Faerm, 2023, p. 243).

- [Fostering such an inclusive environment] supports and develops each student’s sense of belonging and distinct identity [emphasis added] (including the respective student’s values, goals, history, culture, and socioeconomic class) within the community (Lavoie, 2007, as cited in Faerm, 2023, p. 243).

Key Idea 3

Ensure positive group dynamics.

When facilitating collaborative learning, we must give concerted attention to group dynamics: if a group is dominated by more assertive students, particularly ones whose behavior may exclude others from full participation, we must intervene to guarantee we receive feedback from all students. This will ensure a sense of inclusion and of belonging throughout the complete class (Faerm, 2023, p. 247).

Key Idea 4

Cultivate relationships and community.

Creating moments to personally connect with each student and resultantly strengthen a sense of community among our students is a core technique for supporting students’ feelings of belonging and inclusion. Simple acts like asking students what they hope to gain from the course, how they’re doing in their other courses, and what hobbies or extracurricular interests they have will demonstrate your care and genuine concern for them. These practices also allow you to see students as individuals who possess distinct backgrounds, needs, goals, and learning styles. This is critical information you need in order to shape your teaching to be centered on inclusivity—and the importance of the individual—as opposed to exclusivity or bias (Faerm, 2023, p. 249).

Additionally, the SAM II Team Performance Standards table in Figure 8 offered valuable insights more broadly on group dynamics and the conditions for positive and thriving groups as “communities.”

Figure 8

SAM II Team Performance Standards Table, From Lencioni (2002)

The key Team Dimensions of Trust, Conflict, Commitment, Accountability, and Results, while applicable for all group dynamics, offer a rubric of goals and successful outcomes for the Design Studio Group Project, where so many obstacles and challenges must be navigated with great awareness of the above dimensions.

With these principles and approaches in mind, I offered the following case studies at the Mid-Year FLC Lab.

Shireen’s Ongoing Quest for Community: “From the Dreaded Group Project” to “Community and Values Guided Parallel Play”Shireen’s Ongoing Quest for Community: “From the Dreaded Group Project” to “Community and Values Guided Parallel Play”

Case Study 1: A Beginning of Semester Partner Project (Fall 2022).

Semester Theme: THE BODY (and Fashion)

Pair Project: The BODY as SYSTEM (UNGRADED ORIENTATION three-week exploration)

First step: Students arrive to first class and are immediately paired with another student. These students become a “system.” Each “body” merges into one “body/system” in keeping with the overarching semester theme.

Assignments and Class Activities strike a balance between individual and pair work while exploring the skills and work of the class. Students are NOT graded during this period, allowing for a “safe” space to get to know one another and to get to know the course (and me).

The project theme is about understanding the body as a system—a series of interconnected but individual and distinct parts, functioning as a unified “whole.” Thus the partner project asks the pair to function as a “body” to establish a co-created systems for learning and participating in the course and content.

This experience allowed students to feel supported and encouraged their curiosity and sense of play during the first weeks of the fashion program, while giving me a sense of their skill sets, personalities, and needs before kicking off with the first “official” project where students will be graded.

With these principles and approaches in mind, I offered the following case studies at the Mid-Year FLC Lab.

Shireen’s Ongoing Quest for Community: “From the Dreaded Group Project” to “Community and Values Guided Parallel Play”Shireen’s Ongoing Quest for Community: “From the Dreaded Group Project” to “Community and Values Guided Parallel Play”

Case Study 1: A Beginning of Semester Partner Project (Fall 2022).

Semester Theme: THE BODY (and Fashion)

Pair Project: The BODY as SYSTEM (UNGRADED ORIENTATION three-week exploration)

First step: Students arrive to first class and are immediately paired with another student. These students become a “system.” Each “body” merges into one “body/system” in keeping with the overarching semester theme.

Assignments and Class Activities strike a balance between individual and pair work while exploring the skills and work of the class. Students are NOT graded during this period, allowing for a “safe” space to get to know one another and to get to know the course (and me).

The project theme is about understanding the body as a system—a series of interconnected but individual and distinct parts, functioning as a unified “whole.” Thus the partner project asks the pair to function as a “body” to establish a co-created systems for learning and participating in the course and content.

This experience allowed students to feel supported and encouraged their curiosity and sense of play during the first weeks of the fashion program, while giving me a sense of their skill sets, personalities, and needs before kicking off with the first “official” project where students will be graded.

Figure 9

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Showing the First Assignment of the Two-Week “Partner Project”

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Showing the First Assignment of the Two-Week “Partner Project”

Figure 10

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Showing the Final Assignment of the Two-Week “Partner Project”

Students co-create content based on their emerging knowledge and experience of their partner/system. They are then asked to submit a written reflection (from prompts provided by me) on the experience of beginning the semester with a “no grade” Orientation Partner Project.

This experience, while presented as an orientation, also serves the socio-emotional needs of the students by establishing a culture of community through a sense of security, accountability, and safety. Students expressed in their reflections afterward that, while they were, at first, trepidacious about partnering with a stranger, they concluded by having found a friend and partner with whom to embark on the journey of the course experience.

Case Study 2: End of Semester “Design Collective” (Fall 2021).

Semester Theme: THE BODY (and Fashion)

First step: Students each do their own research on possible topics around Body and Fashion, affirm their own area of curiosity, and connect with their own “WHY.” Examples of topics included: anti-Asian hate and racism through fashion, class and exclusion through fashion, body positivity and racism, etc.

Second step: Once they identify a topic and articulate why it MATTERS through their research and first draft proposal, they arrive at the “shop-around activity.” In this whole-group class activity, students hear each other’s presentations of topic research and areas of interest and “shop around,” seeking to align with like-minded proposals and come together to support the work of creating an immersive project to visually communicate their point of view and vision for the future of this topic through the lens of fashion.

Third step: Once grouped together, the group members will work to re-examine and re-affirm common goals/objectives/message based on the tasks/deliverables of the project brief. The group then works toward creating the suite of elements needed for the ultimate collective experience.

Figure 11

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Individual Research Topics Presentations

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) Individual Research Topics Presentations

Students present their chosen topic during the “shop-around activity,” while fellow students place post-its of the overarching themes that they feel are being expressed.

Figure 12

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) “Shop-around activity”

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) “Shop-around activity”

The week after the “shop around,” students present additional research and ideation. Students then “sign up” to be considered for various groups that also align with the shared themes of their chosen topics. Ultimately, the groups are self-selected or selected with a bit of logistical support from me.

The culture of community that’s been formed by the end of the semester has already provided students with a sense of safety and belonging. By shifting the agency of choosing how the groups are formed, students are embarking on the group’s creative journey already feeling a sense of belonging and shared values and interests.

Forming Our Own Community as Educators to Educators (to Students!)

During this mid-year presentation, we researchers, as a cohort, expressed overlapping explorations and interests. True to my brand, as a perpetual seeker of community, I put out a call for like-minded peers who would be willing to work together on the theme of community in our own supportive network. Natalie and Caroline, who were also exploring the creation of systems of supports for educators and students from different lenses, answered the call, and we forged our community of accountability, shared labor, shared talents, and, above all, spaces of shared empathy and respect.

Finding connections across our research, we decided to not only share our work in the classroom with our students, but also to create a resource that fellow faculty could try in their own classrooms. We met biweekly and identified the overlaps and shared core ideas of our mutual research.

While Caroline remained with us for the planning phase and the valuable solidarity, she joined another FLC partner to complete work on a similar research project. Our meetings began by discussing what we were doing in our own classrooms, our successes and stumbling blocks, and sharing ideas of how to improve community, equity, and support. We created lists to share and learn from each other. Finding this resource helpful, we reached out to the CTL to propose a workshop modeled on sharing and building upon these strategies.

Below is the description and visual documentation of our workshop:

Workshop Proposal: Community, Inclusion, and Belonging in the Classroom

AUDIENCE: College-level educators in fine arts and design who require group work.

GOAL: Share strategies and practices to ensure classrooms provide community, inclusion, and belonging; this includes reframing, iteration, reflection, and adjusting how we share and receive information.

ONE-SENTENCE DESCRIPTION: Exchange basic frameworks and best practices for cultivating inclusive classroom experiences for higher education art students; build confidence to iterate and adjust to your student dynamic with support of fellow educators.

Figure 13 is a screenshot from the Miro board designed for the interactive workshop held on September 26, 2023. Offered as a Faculty Spotlight through the CTL, the workshop was promoted to Pratt faculty across disciplines. We offered spaces for conversation, resources, and case studies of key ideas and practical strategies for the higher ed classroom to fellow educators and “community seekers.”

Figure 13

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) of Building Community Workshop

Screenshot of Class Mural (Whiteboard) of Building Community Workshop

References

Eliot, T. S. (1943.) Little Gidding. Four quartets. Gardners Books.

Faerm, S. (2023). Introduction to design education: Theory, research, and practical applications for educators. Routledge.

Lencioni, P. M. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team. Jossey-Bass.

Lerman, L., & Borstel, J. (2003). Liz Lerman's critical response process: A method for getting useful feedback on anything you make from dance to dessert. Liz Lerman Dance Exchange.

McAleer Balkun, M., & Radwan, J. (2022, May 2). Building community in times of crisis. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/academic-leadership/building-community-in-times-of-crisis/.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.