<--

Issue 04

2024

Issue 4 ︎︎︎

Click to read all of Issue 4

Contents

“A Sense of Belonging”: Alternative Assessment in the First Year ︎︎︎

Growth-Centered Learning:

A Non-Grading, Feedback-Oriented Approach ︎︎︎

Embodying Playfulness for Inspiring Quality Presence and Authentic Creativity in the Classroom ︎︎︎

In Conversation with Growth ︎︎︎

Inclusive Pedagogy:

Creating adaptive spaces for a spectrum of learners to access metacognitive skills ︎︎︎

Problem Solving ︎︎︎

Quest for Community ︎︎︎

Performing Theory: Interweaving Body, Space, and Text ︎︎︎

Reconsidering the Term Project: Reflections on a Community of Inquiry and Practice ︎︎︎

Issue 04

2024Issue 4 ︎︎︎

Click to read all of Issue 4

Contents

“A Sense of Belonging”: Alternative Assessment in the First Year ︎︎︎

Growth-Centered Learning:

A Non-Grading, Feedback-Oriented Approach ︎︎︎

Embodying Playfulness for Inspiring Quality Presence and Authentic Creativity in the Classroom ︎︎︎

In Conversation with Growth ︎︎︎

Inclusive Pedagogy:

Creating adaptive spaces for a spectrum of learners to access metacognitive skills ︎︎︎

Problem Solving ︎︎︎

Quest for Community ︎︎︎

Performing Theory: Interweaving Body, Space, and Text ︎︎︎

Reconsidering the Term Project: Reflections on a Community of Inquiry and Practice ︎︎︎

<--

Brian Brooks, Maura Conley, Heather Lewis, James Lipovac, and Micki Spiller

“A Sense of Belonging”: Alternative Assessment in the First Year

Brian Brooks, Maura Conley, Heather Lewis, James Lipovac, and Micki Spiller

This article describes emergent research findings from an ongoing qualitative research study of a cross-departmental alternative assessment pilot at Pratt, with a specific focus on Pratt’s undergraduate Foundation program. The quantitative research component of the pilot will be discussed in a future article. While the pilot also included faculty in other departments (Humanities and Media Studies, History of Art and Design, Graduate Communication Design) this article focuses on the qualitative research conducted by Foundation faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC). Preliminary findings suggest that learning in the gradeless studio is grounded in instructional practices that promote a “sense of belonging” for both students and professors, as well as a place in which self-assessment, reflection, and feedback are valued and practiced.

Alternative Assessment (Gradeless) Pilot

The pilot grew in scale over three years, informed by James Lipovac’s research in 2019 when he was awarded a Faculty Fellowship in Foundation from Pratt Institute’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) to study methods of un-grading in his first-year studio art course. By the time he started his research, COVID was everywhere and the move to remote learning had already begun. That spring, virtually all colleges in America switched temporarily to pass/fail. This seismic shift was quickly followed by the cultural awakening precipitated by the murder of George Floyd. Both events turned many academic traditions on their heads across the country.

James’s work on ungraded assessment became unexpectedly relevant and exciting to colleagues at Pratt, generating a Gradeless Assessment Pilot beginning in academic year 2020–21 with three professors and eighteen students in the Foundation department, expanding to twenty-five professors and 132 students in academic year 2021–22, and to a cross-institutional pilot in 2022–23 involving eight professors and thirty students in History of Art & Design, Art & Design Education, and Humanities and Media Studies, and six classes with seventy students in Graduate Communication Design. Though students knew they were in a gradeless pilot program, students also knew that, ultimately, they would receive a grade on their transcript. A total of more than 200 students taking courses across seven disciplines within three departments participated. Despite the fact that this work has yet to be officially institutionalized, faculty have nonetheless started to reshape teaching and learning at Pratt as a result.

Over the past five years, faculty across Pratt engaged in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in diverse areas such as the transfer of learning, learning as narrative, learning in the first year, and critique as a signature pedagogy in art and design education. Faculty research on critique (Crit the Crit Faculty Learning Community, 2016–2019) explored studio-based critique methodologies and typologies used at Pratt in art and design disciplines. This led to a subsequent publication, which theorized critique and power (Martin-Thomsen, et al., 2021) and institute-wide explorations of gradeless assessment and non-inclusive forms of critique. Through the CTL’s Faculty Fellowship (2021) and Gradeless Assessment Deep Dive Community (2022), faculty researched alternative approaches to assessment. A description and examples of some of the work are available on the CTL website.

This article is based on recent action research conducted by faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC) in their courses and programs over the 2022–23 academic year. Faculty reviewed literature in the field on feedback and alternative assessment (Winston & Boud, 2022; O’Donavan, et al. 2021; Winstone, et al., 2017; Molloy, Boud, & Henderson, 2021), posted their teaching artifacts on a shared Milanote board, shared their research at monthly FLC meetings, and analyzed their teaching through narrative inquiry. While this article constitutes a snapshot of ongoing research, the emergent findings and a review of the existing literature in the field of alternative assessment and feedback suggest that Pratt’s pilot work in this area offers a strong contribution to the field given its scope as well as depth. It also suggests that the small, significant networks of SoTL practitioners in the area of alternative assessment provide a foundation on which to expand alternative assessment at Pratt (Verwood & Pool, 2016).

The pilot grew in scale over three years, informed by James Lipovac’s research in 2019 when he was awarded a Faculty Fellowship in Foundation from Pratt Institute’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) to study methods of un-grading in his first-year studio art course. By the time he started his research, COVID was everywhere and the move to remote learning had already begun. That spring, virtually all colleges in America switched temporarily to pass/fail. This seismic shift was quickly followed by the cultural awakening precipitated by the murder of George Floyd. Both events turned many academic traditions on their heads across the country.

James’s work on ungraded assessment became unexpectedly relevant and exciting to colleagues at Pratt, generating a Gradeless Assessment Pilot beginning in academic year 2020–21 with three professors and eighteen students in the Foundation department, expanding to twenty-five professors and 132 students in academic year 2021–22, and to a cross-institutional pilot in 2022–23 involving eight professors and thirty students in History of Art & Design, Art & Design Education, and Humanities and Media Studies, and six classes with seventy students in Graduate Communication Design. Though students knew they were in a gradeless pilot program, students also knew that, ultimately, they would receive a grade on their transcript. A total of more than 200 students taking courses across seven disciplines within three departments participated. Despite the fact that this work has yet to be officially institutionalized, faculty have nonetheless started to reshape teaching and learning at Pratt as a result.

Over the past five years, faculty across Pratt engaged in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in diverse areas such as the transfer of learning, learning as narrative, learning in the first year, and critique as a signature pedagogy in art and design education. Faculty research on critique (Crit the Crit Faculty Learning Community, 2016–2019) explored studio-based critique methodologies and typologies used at Pratt in art and design disciplines. This led to a subsequent publication, which theorized critique and power (Martin-Thomsen, et al., 2021) and institute-wide explorations of gradeless assessment and non-inclusive forms of critique. Through the CTL’s Faculty Fellowship (2021) and Gradeless Assessment Deep Dive Community (2022), faculty researched alternative approaches to assessment. A description and examples of some of the work are available on the CTL website.

This article is based on recent action research conducted by faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Faculty Learning Community (FLC) in their courses and programs over the 2022–23 academic year. Faculty reviewed literature in the field on feedback and alternative assessment (Winston & Boud, 2022; O’Donavan, et al. 2021; Winstone, et al., 2017; Molloy, Boud, & Henderson, 2021), posted their teaching artifacts on a shared Milanote board, shared their research at monthly FLC meetings, and analyzed their teaching through narrative inquiry. While this article constitutes a snapshot of ongoing research, the emergent findings and a review of the existing literature in the field of alternative assessment and feedback suggest that Pratt’s pilot work in this area offers a strong contribution to the field given its scope as well as depth. It also suggests that the small, significant networks of SoTL practitioners in the area of alternative assessment provide a foundation on which to expand alternative assessment at Pratt (Verwood & Pool, 2016).

Internal and External Contexts

Pratt’s Gradeless Assessment Pilot is part of a broader focus on equity in assessment in higher education across the country (Montenegro & Jankowski, 2020; McArthur, 2019). The more recent effects of equity reforms in higher education, as well as decolonizing the curriculum in higher education, sparked a re-examination of assessment practices not only at Pratt, but also nationally and internationally (Bhumbra, 2018).

Though Pratt's transition to pass/fail during the first COVID semester felt like a quick pivot necessitated by the pandemic, the Foundation department adapted gradeless practices with the hopes of building something intentional, more sustainable, and well-scaffolded for professors and students alike. To that end, Lipovac (personal communication, 2022) explains how the gradeless approach has shifted in Foundation over the years:

Pratt’s Gradeless Assessment Pilot is part of a broader focus on equity in assessment in higher education across the country (Montenegro & Jankowski, 2020; McArthur, 2019). The more recent effects of equity reforms in higher education, as well as decolonizing the curriculum in higher education, sparked a re-examination of assessment practices not only at Pratt, but also nationally and internationally (Bhumbra, 2018).

Though Pratt's transition to pass/fail during the first COVID semester felt like a quick pivot necessitated by the pandemic, the Foundation department adapted gradeless practices with the hopes of building something intentional, more sustainable, and well-scaffolded for professors and students alike. To that end, Lipovac (personal communication, 2022) explains how the gradeless approach has shifted in Foundation over the years:

Initially, focus was on faculty assessments of the students. As the pilot evolved, that has shifted nearly completely to student assessments supported by faculty and peer feedback. Faculty are taught, through a series of workshops, to forgo not just grades, but also traditional summative assessments, in favor of well-timed feedback sessions designed to help the students self-reflect and take the lead in their own learning.

The following infographic provides a snapshot of the relationship between the Gradeless Assessment Pilot and Foundation Program Learning Outcomes.

Figure 1

Foundation Department Learning Outcomes Aligned With Gradeless Assessment Pilot

This article focuses on qualitative research by six Foundation faculty in the Gradeless Assessment Pilot.

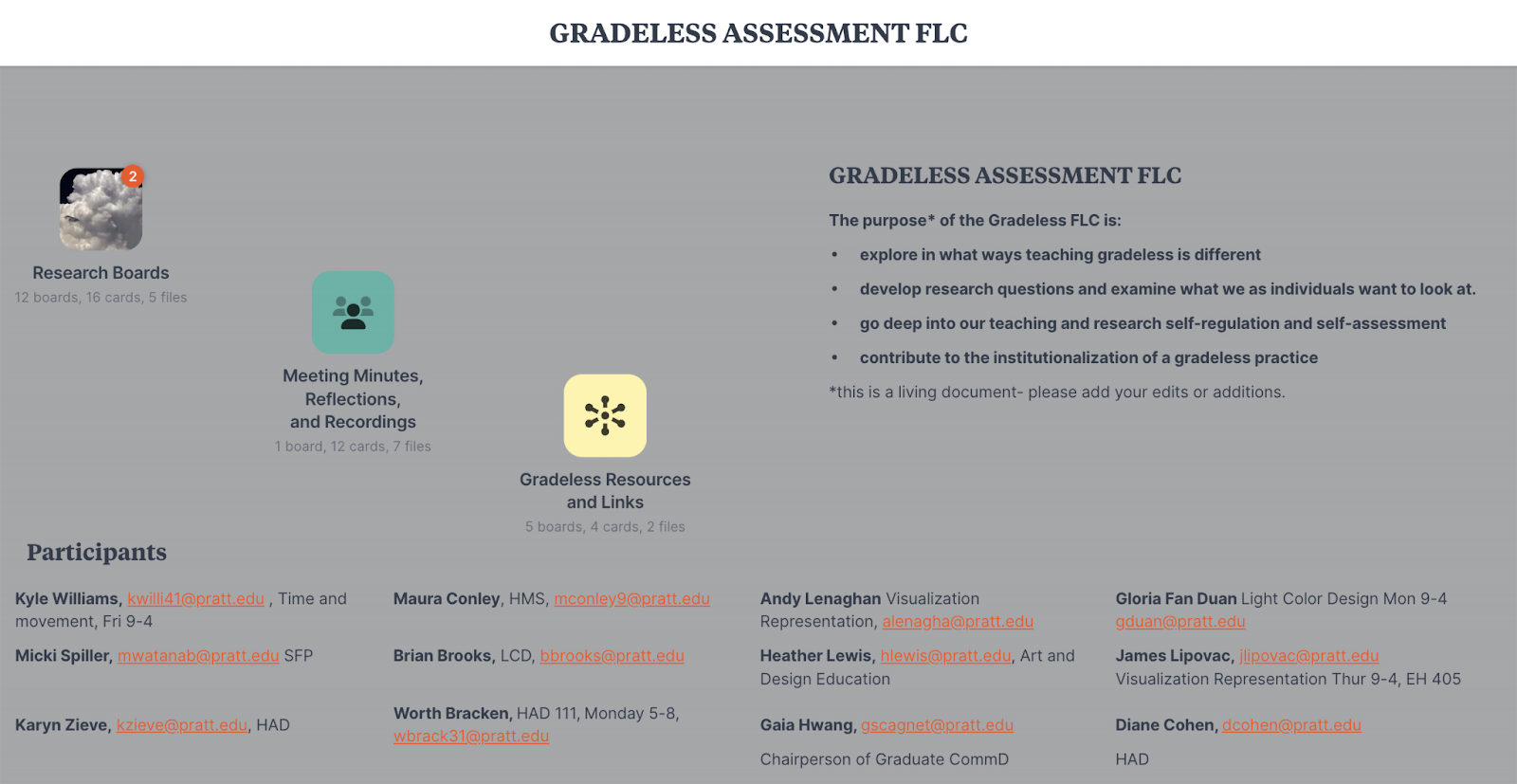

Faculty Learning Community Participants and Process

In the academic year 2022–23, the Foundation department supported a Faculty Learning Community consisting of eleven faculty members from four departments and the CTL (see list below). All members of the FLC studied their courses over two semesters. FLC members agreed to an overarching FLC research question: How has (gradeless) assessment changed how we teach? Each individual faculty member then developed a related research question specific to their course. The FLC discussed a shared reading about feedback and reflection (Winston & Boud, 2022), developed a research plan, and analyzed their teaching based on the evidence they collected through narrative inquiry (Leiblich et al., 1998). Everyone shared their work on Milanote and in monthly FLC meetings that featured two to three faculty members’ emergent findings each month.

The faculty research boards in Figure 2 illustrate the work of six FLC faculty members from the Foundation department. Each faculty member introduced student reflection and/or student self-assessment in their classes through such practices and processes as digital journals, ongoing reflective benchmarking processes, process books that include self-assessment, faculty and peer feedback, and structured, cumulative reflection.

Figure 2

FLC Milanote Board

The following are brief summaries describing an instructional intervention, research question, and subquestions in one of the gradeless courses. FLC Milanote Board

Kyle Williams: Student Digital Open Journal

Course: Time and Movement

Figure 3

Student Digital Open Journal

Student Digital Open Journal

Instructional Intervention Description

Using the Milanote digital platform, each student creates a board to be their unique journal.

- The journal is meant for students to reflect and process information without the context of a public forum. However, it is not private. It is also meant to be a place where the student and I can share information.

- Each class, the students answer a question or reflect on a topic I give them in their journal. When questions are analytical, I begin with a low-stakes free-writing prompt.

- Journal questions/topics ask students to reflect on the work that they and their peers are making, including reflecting on class critiques and works in progress. This includes asking students to copy and paste the work of their peers and their own work into the Milanote board to discuss and assess it.

- Talking about peers’ work is just as important as talking about their own work.

- There is no prescribed format for this—it is not something that needs to look good.

- I respond to posts within the journal.

Overall, the open journal should be a place where students are practicing the skills of describing how and why a project works as well as a place where I can respond to their writing and their work with feedback. It should be a place where I can model how to evaluate projects and how to connect ideas we cover in class to the work they are making.

Research Question and Subquestions

How can a shared digital journal be an effective platform for faculty feedback and students' self-regulated learning?

- Is it possible to find a balance of a semi-private space to write that is also a shared space between the teacher and student, and that can be secured from other students reading it? Can this "semi-private" status be presented as a positive? The idea of "learning in public."

- Logistically, is it possible for the teacher to make the time commitment to actively engage with each student on the journal effectively?

- How can I make written self-assessments not feel like busy-work?

- Can this reflective journal effectively be used to model, through feedback, how to look at / think about / speak about work and how to connect making to our class concepts?

Andy Lenaghan: Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Course: Visualization and Representation

Figure 4

Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Ongoing Reflective Benchmarking Process

Instructional Intervention Description

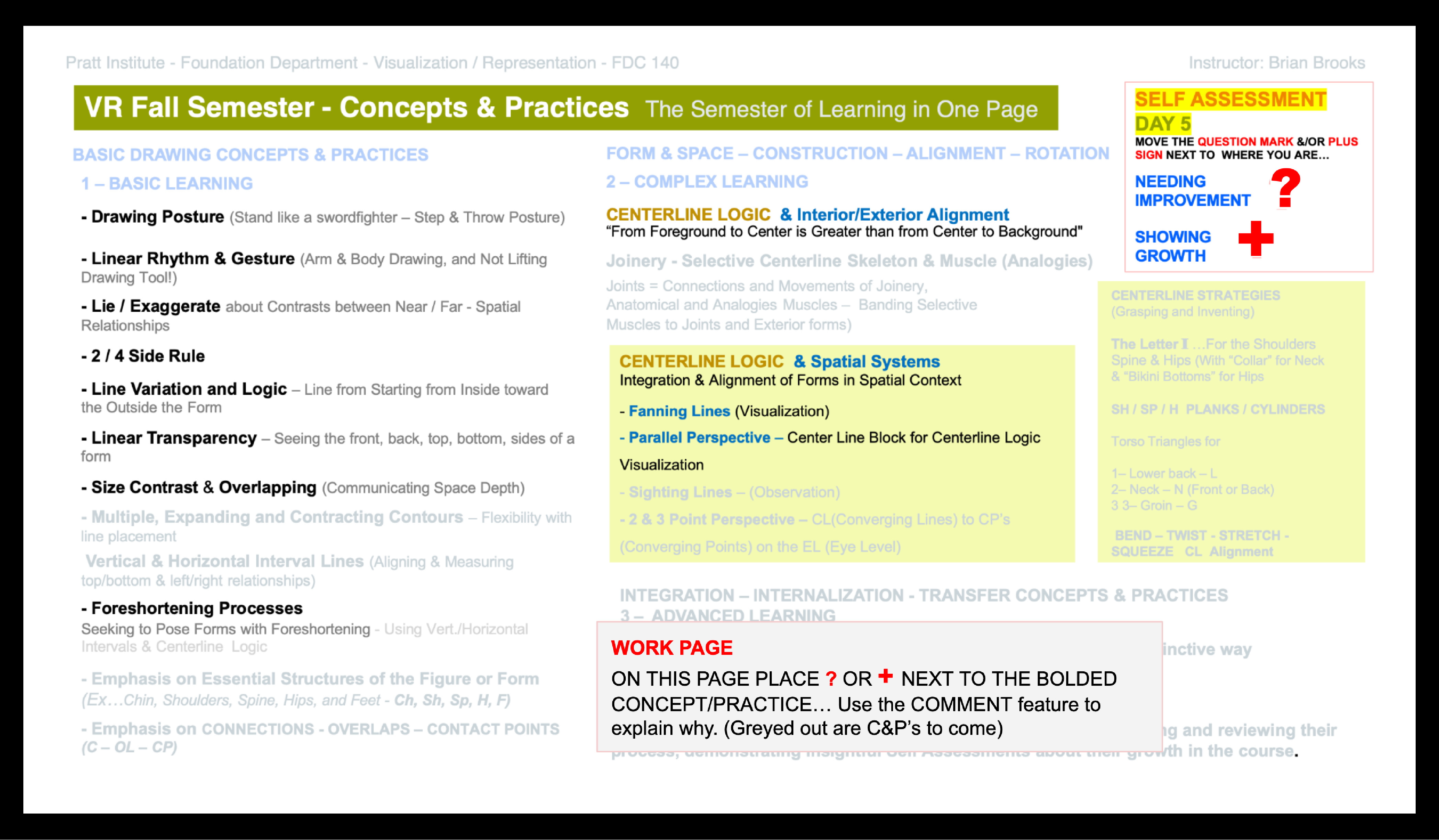

Self-assessment as a goal of the course is introduced and sustained throughout the course with student writing exercises that benchmark student progress. This intervention provided knowledge about the student’s verbal understanding of the course outcomes from the beginning to the end of the course. Through the ongoing reflective benchmarking process, students participated in self-assessment in writing and image selection according to attributes.

Research Question

Can students self-assess and demonstrate their understanding of course outcomes verbally and in their work without a grade as motivation?

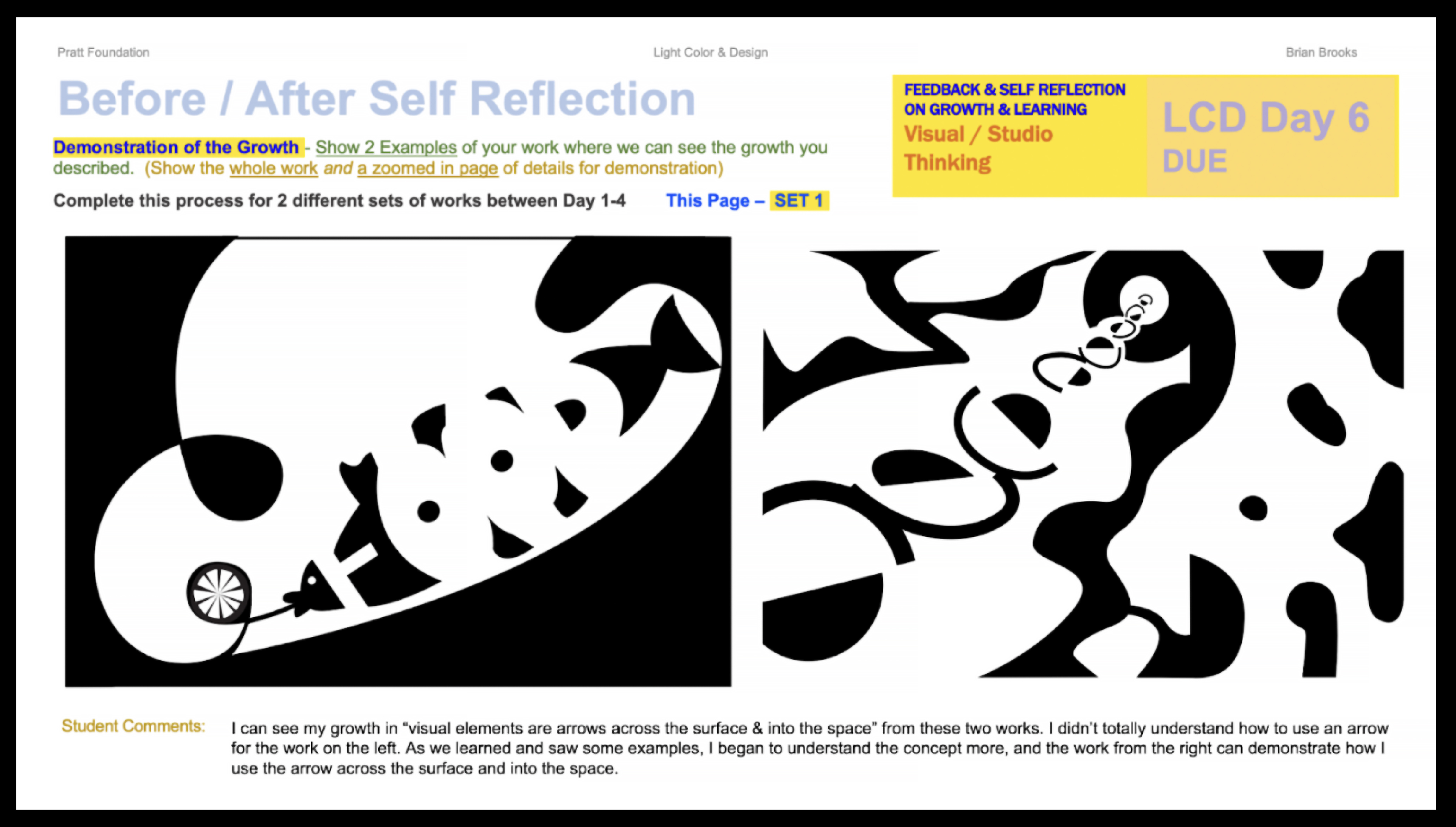

Brian Brooks: Student Process Books (for Reflection and Feedback)

Course: Light, Color, and Design

Figure 5

Process Book

![]()

Process Book

Instructional Intervention Description

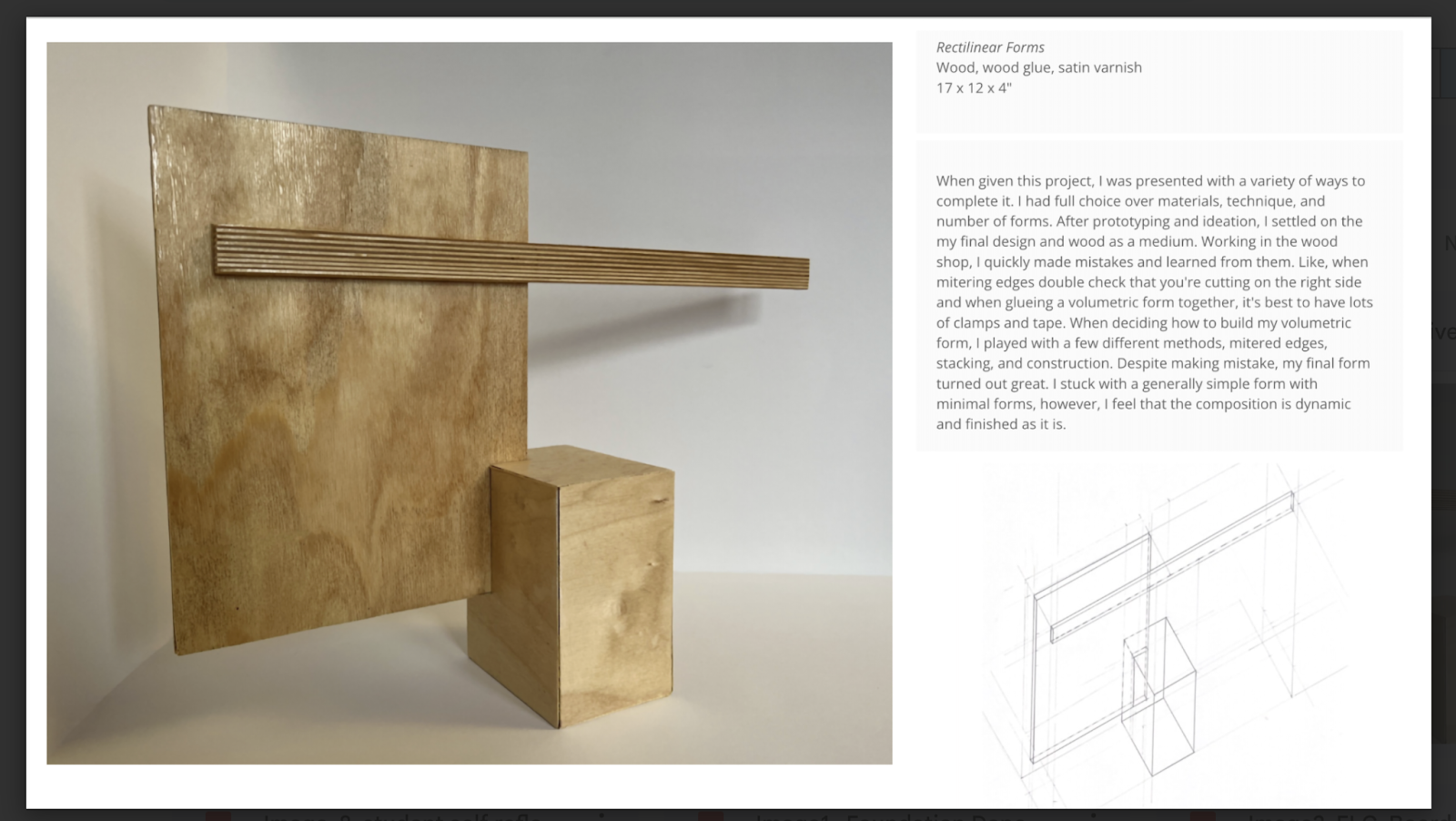

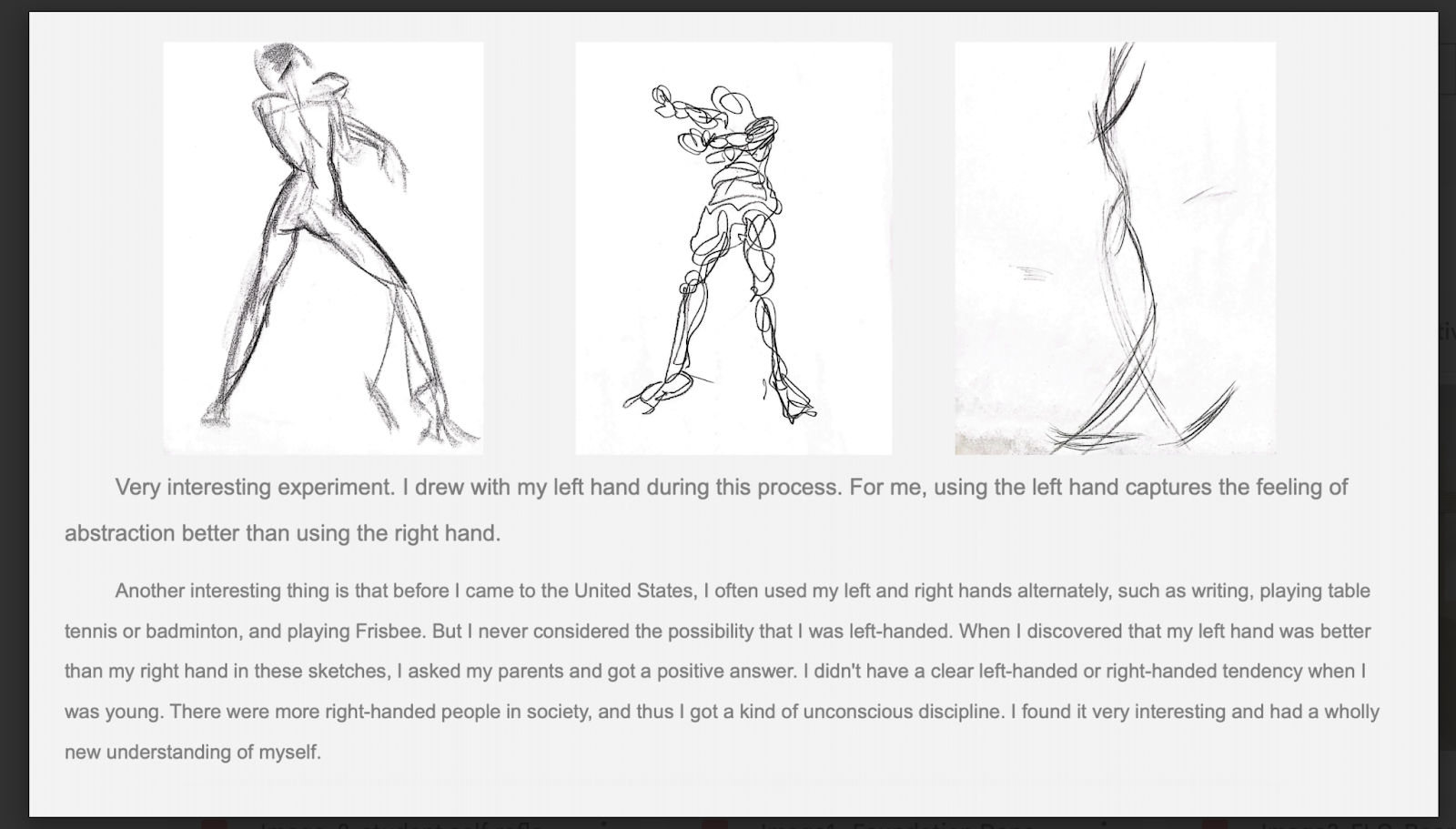

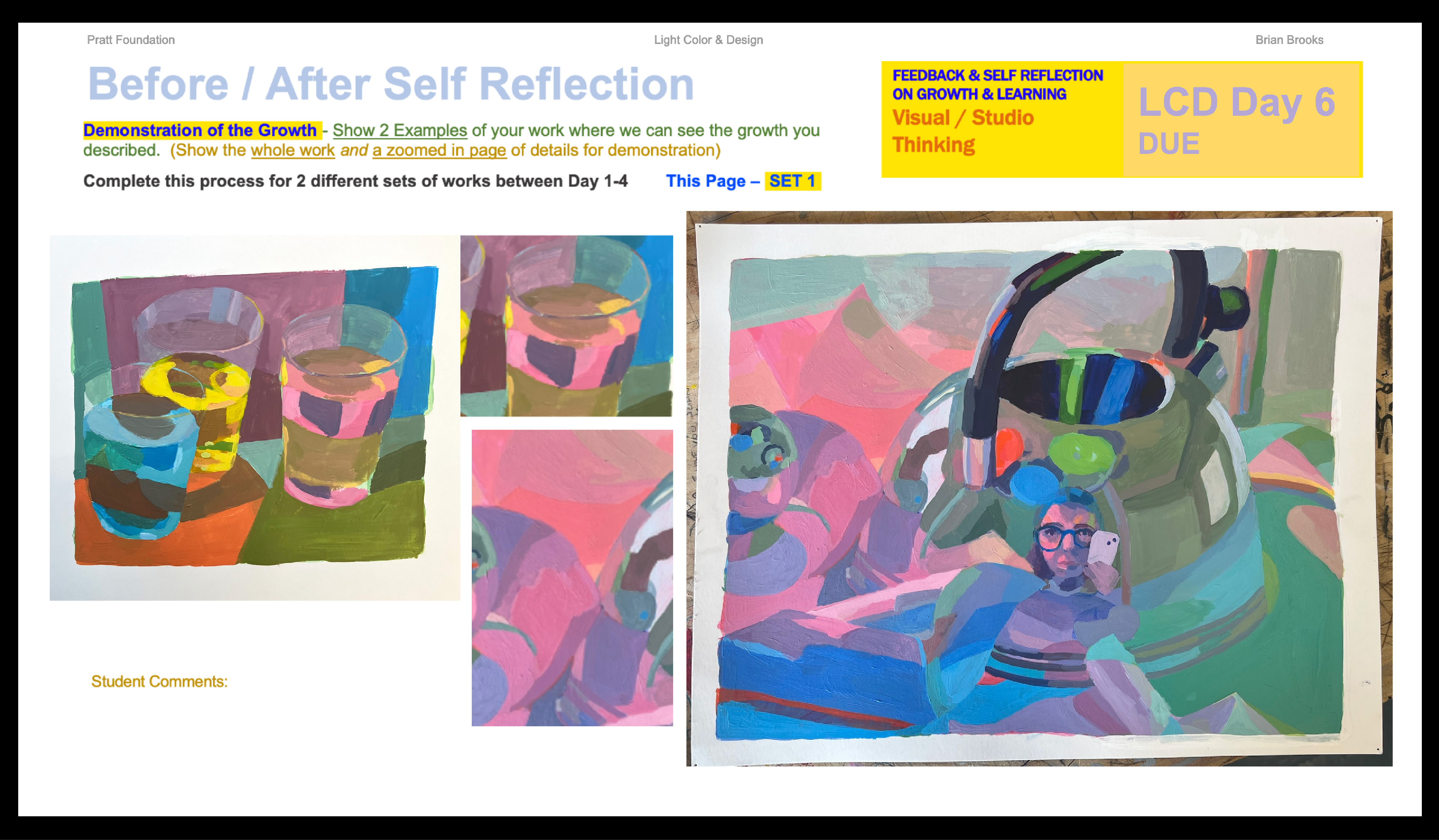

In this course, the students document their semester-long work in an Individual Process Book using a Google Slide template created for depositing all works in progress and completed classwork (CW) and homework (HW) assignments. I emphasized work in progress because the overall theme of the course, as far as learning goes, is growth… in a student’s learning process. The teacher watches growth and helps students look for and recognize it. This is the feedback conversation about learning that far outweighs the value of grades. A student grasping their growth and development seems to anchor their course learning on concrete products and processes used in class, which I suspect helps them identify their growth and test it in the future.

Research Question and Subquestions

How can we assess students without grades?

- How can I assess students without grades?

- What have grades helped students learn, and what is the best alternative to using grades?

- What is essential to a student’s learning process?

- What are the least “invasive” ways to create self-reflection in students that generates conversations and self-awareness and that helps them:

- See strengths in their processes

- More accurately pin-point where “improvement” can happen in “grasping concrete learning objectives & concepts” in the course

- Develop multiple areas of practice (where concepts have multiple uses, applications, and paths for transfer to develop learning course concepts)

- Reinforce their strengths and aim more closely and specifically at where they need to improve

- Make the self-reflective process more visual and concrete

Micki Spiller: Reflective Writing

Course: Space, Form, and Process

Figure 6

Reflective Writing

Reflective Writing

Instructional Intervention Description

This is a mandatory one-semester first-year class focusing on fundamental principles of 3D design and techniques of haptic building. The instructor and peers give feedback and assess with the use of rubrics throughout the course. The students and instructor discuss the student’s final grades through self-reflection (see Figure 6).

Table 1

Stages of Self-Reflection and Feedback

Stages of Self-Reflection and Feedback

Research Question

In a first-year course, what replaces a student's primary motivation tool when grades are no longer used?

- Reflection helps students to think about the learning outcomes and how they have met them two times a semester.

- Students are more involved in their own learning.

- Focus is on assessment of individual ability to progress rather than of prior knowledge.

James Lipovac: Structured Reflection and Feedback on Self-Regulation

Course: Visualization and Representation

Figure 7

Screenshot of Student Self-Reflection About Self-Regulation

Screenshot of Student Self-Reflection About Self-Regulation

Instructional Intervention Description

James helped students monitor and assess their progress with regards to:

- risk taking

- problem solving

- time management

- community interaction

- communication skills

- technical proficiency

A focus has been placed in the course on moving up the timing of faculty feedback to happen earlier in the creative process in an effort to provide students with constructive support with enough time to act on it. By moving up the feedback, students will be empowered to experiment with peer, self, and faculty feedback.

Research Question

How can faculty and peer feedback affect self-regulation?

Emergent Themes

Based on faculty narrative inquiry, the following themes emerged across individual faculty research: building community, the value and challenge of reflection in the curriculum, changing faculty teaching practices, and encouraging student ownership of their learning and assessment fluency. The following sections provide a brief description of two of the themes illustrated with quotes from faculty summarizing their findings in response to their research questions. Further analysis, beyond the scope of this article, is vital to fully understand how gradeless teaching and learning changes the way we think about building community, curriculum content, and how students take ownership of their learning.

Building Community

A sense of belonging is essential to student success, especially in the first year. Belonging leads to higher performance, but even more importantly, is linked to a student’s persistence and overall mental health and well-being (Gopalan and Brady, 2019). Through the reflective writings, many of the participants in the FLC reported that, without the use of grades as a tool to potentially divide students, other aspects of “success” in a course could take center stage. Building community took two main forms: student community within the studio and professor as learning partner.

With the removal of traditional grading practices and a reorientation toward self-assessment, a greater sense of community was felt by professors and students alike. Andy noted that, “I believe students welcome the relief from external judgment and that this instills a sense of community. Students who feel part of that community are happier and more likely to have fond and lasting memories of the course.” Other FLC participants reported a similar feeling that—while a grade might feel like an independent project within a class, an avenue between professor and student—gradeless assessment, in the form of self-reflection and peer feedback, has the potential to be a community (classroom) project.

Additionally, Brian noticed that not only was the sense of community something he sought to cultivate with his students across the semester, but it is also something that he is profoundly implicated in and impacted by:

When the course acts like a “learning community,” each person’s growth and learning contributes to everyone else's. My own role in the course/community is to learn from every generation of students who push me to improve on my grasp of the course material and to strive in becoming a more sensitive and effective teacher. I am learning with my students.

Similarly, Andy deepened his understanding of community:

I turned to writing as a tool to measure student understanding much more than I have in the past. Maybe just as importantly, this experience has served to expand my own personal thinking and understanding to other department initiatives such as parallel teaching across multiple courses and departmental outcomes such as “community.”His notion of parallel teaching would mean that professors teaching the same courses would be matched so that they could share teaching insights to “propel inquiry and synthesis.”

The Values and Challenges of Reflection, Self-Assessment, and Feedback

Faculty introduced a more structured form of written reflection into their gradeless courses than they had previously. Andy noted that:

The focus on written reflection was an opportunity to gain insight into questions that had been brewing in my mind for years. It was a chance for students to go further in their thinking about synthesis and inquiry. I found the prompts and answers to the questions to be very revealing for me personally. Responses fit into three categories: students who have gained fluency and understanding of the verbal content, students who have memorized terms and definitions, and students who are struggling with both verbal fluency and understanding.

Brian has been working to integrate self-assessment into his course for many years, in part through a tool called the “individual process book” (see above). Brian noted that the process books are

[i]n essence… public and private opportunities to watch growth captured in a linear view of the student working. Because students are asked to take photos of their work as they are working, it “slows the class down” and “forces students to look at unexpected intervals… and in doing so, NOTICE things.

However, across most of these highlighted courses, faculty also noted that the introduction of slowing down or adding additional reflective writing and documentation also created challenges for adding these rich alternate forms of assessment into an already packed fifteen-week curriculum. The professors in the FLC often shared a sense of overwhelm, seeing the value of written and reflective assessment while also keeping up with the expectation to deliver their established curriculum. Micki noted that:

The time commitment of self-reflection was added to an already full course. [There was a] problem of what to take out to replace the writing/self-reflection component. As much as I would have liked to provide some class time for self-reflective writing, I could not omit any content to replace the time needed for student self-reflection.

Andy noted that “it also requires a time commitment for both faculty and students that comes at a loss of making work.” In contrast, James argued that a shift to feedback within a skill-based learning environment has been unique. He suggests that there is no diminishing of skill-based learning within the gradeless environment.

Students’ sample responses to the gradeless environment appear to support James’s claim. While the following quotes from his students in response to a set of prompts are not representative of all students, they illustrate student understanding of the value of the instructional interventions in their own learning. One student noted that:

I learned to value the feedback and critique of my classmates and professor over a grade, because their input is what helps me refine my work and push myself to improve. Additionally, I learned how to give constructive and important critique to my classmates.

Another student addressed the value of combining feedback with skill-building: “Self-assessment makes it much easier to individually understand how far I've developed my skills. Professors still make clear whether or not I am succeeding with feedback.” Clearly, future research will need to incorporate student voice, not only through individual responses, but also in the overarching pilot.

Conclusion

This brief analysis of two emergent themes in the FLC research is small-scale. However, the themes that emerged—building community and reflective practices—suggest that faculty instructional practices, while somewhat different and unique, supported different types of reflection, self-assessment, feedback, and community-building in a gradeless context. This does not mean that it is impossible to promote and sustain such instructional interventions in a traditional (i.e., graded) setting, but it suggests that a gradeless context combined with such interventions can provide a conducive setting for students to grow as learners and makers through alternative assessment. And without such interventions, a gradeless approach may not necessarily contribute to student learning.

The continuation and expansion of the Gradeless Assessment Pilot requires administrative support at all levels. Indeed, administrative support from the former associate provost and department chairs was critical to the launch and implementation of the pilot. However, further support is essential in order to address the structural changes necessary to embed alternative assessment into the curriculum and pave the way for institutionalizing alternative assessment in art and design.

References

Bishop-Clark, C. U., Dietz, B., & Cox, M. D. (2014). Developing the scholarship of teaching and learning using faculty and professional learning communities. Learning Communities Journal, 6, 31–53.

Bhambra, G. K, Nişancıoğlu, K., & Gebrial, D. (Eds.). (2018). Decolonizing the university. Pluto Press.

Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19897622

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985253

Martin-Thomsen, T. C., Scagnetti, G., McPhee, S., Akenson, S. B., & Hagerman, B. ( 2021). The scholarship of critique and power. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 9(1), 279–93. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.19

McArthur, J. (2019). Assessment for social justice: Perspectives and practices within higher education. Bloomsbury Academic.

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2020, January). A new decade for assessment: Embedding equity into assessment praxis (Occasional Paper No. 42). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centered framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45:4, 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

O’Donovan, B. M., den Outer, B., Price, M., & Lloyd, A. (2021). What makes good feedback good? Studies in Higher Education, 46(2), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1630812

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2022). The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 47:3, 656–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2017). “It'd be useful, but I wouldn't use it”: Barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

Verwoord, R., & Poole, G. (2016). The role of small significant networks and leadership in the institutional embedding of SoTL. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20190

Additional FLC Participants

Worth Bracken- Participant (History of Art and Design 111)

Gloria Fan Duan (Quantitative research study on Gradeless Assessment Pilot to be published in the future)

Gaia Hwang (Chair, Grad Com-D, research on Gradeless Assessment Pilot to be published in the future)

Andy Lenaghan- Participant (Foundation)

Kyle Williams- Participant (Foundation)

Karyn Zieve (Assistant Dean, SLAS)

Administrative Support for Pilot

Gaia Hwang, Chair, Graduate Communications Design

Camille Martin-Thompsen, Associate Provost

Leslie Mutchler, Chair, Foundation

The Air in the Studio is Filled with Feedback

Engaging in a shared “Gradeless” cohort offered me a chance to focus only on offering students feedback for learning. This dropped the burden of using grades. I do not use crits, a formal group sit-down reviewing everyone’s work methodically, but have elicited conversations about “noticing,” observing things about the work and asking where someone really innovated with the given assignment. Distinctions between subjective and objective observations are encouraged (if they can be identified by the student). Focusing on where and how course concepts are being used excitingly and where improvements can be made is the key goal for these pin-ups.

Collective conversations are gathering points in class sessions, but feedback conversations are happening throughout the workshop nature of the studio class time. I take open-air walks around the room, continuously observing, coaching, noticing aloud, making references to the collective conversations, helping students one on one publicly and in collaboration with peers. This makes use of many layers of the feedback process. A part of this process is reminding students to photograph their process frequently. Students are regularly asked to come over and see what this or that person has just done. (I purposefully do this with students whose work does not get attention, because in the public nature of the workshop, we are really learning from the diversity of sensibilities in the group.) Through this process, there is no way for students to think I am not giving them regular feedback all the time. It is part of the air of the studio classroom.

Studio makers have a hard time reflecting on their moment-by-moment achievements or where they have strayed from the goals of the assignment, because studio making is a complex, simultaneous, whirling storm of different kinds of activities. We easily become distracted, sidetracked, and sometimes these distractions lead to important discoveries. Sometimes these distractions represent a tendency to avoid hard things to do. That avoidance might translate to comfort, as those behaviors are tendencies learned before coming to college. There is nothing wrong with this. Learning is a challenge, as often it is a space of critical thinking and problem solving within an organized and outcome-based college course.

When students work on homework, they often are not pulled from their moment-by-moment worlds to stop, step back, rotate the work upside down, see it from across the room, look at someone else trying to do the same thing but in a totally different way that can baffle the student or offer infectious influence.

The workshop that includes moment-by-moment feedback models a way to work. Focus, move ahead, and then stop, step back, and reflect.

How can grading capture the dynamics of a feedback-centered workshop? Seemingly, the only possible way is to witness and reflect on the engagement and growth of the student, with consideration for how they internalize the course material and individually put it into motion. A grading system like A, B, C is grossly inefficient. Unless everyone gets an A for engagement, grading is outside of the air and atmosphere in the studio workshop.

A Language of Self-Reflection for the Workshop Learning Process

The required Foundation courses I teach have very large parts of them that will be completely new for first-year art and design college students. Many students begin Foundation at Pratt as fifth-year high school students. The shift in learning is often enormous. Many high school art or design courses are product driven where results of projects are pre-known and pre-exist. Students want me to show them an example of how the final work should look. If I taught a course based on this model, it would make sense to have an A–C grade system. But when teaching a visual-concept- and practice-based course where learning happens by doing individually within the shared collective community of the course, differences in learning re-create the learning material. No semester results in the same achievements because the learner changes the course.

Students in this environment go through the challenging process of learning a visual design principle by experimenting with its components and building upon earlier scaffolding learning components. They are asked to make use of new and previous things learned in new learning problems.

Students in this process commonly say, “I understand it but have a hard time applying it.” Because the air in the studio is filled with feedback, the door opens to a particular use of “Bloom’s Taxonomy” (Armstrong, 2010), making his “learning level vocabulary” concrete and practical and of the moment. The student making this statement (someone every year does so…) indicates that they have a minor crisis in learning. Understanding is one thing, but applying it is another. The student can seem stuck, unable to play, but most often seems to be reporting a gap in rationality and intuition or stating that something is out of reach. This is a minor event, but verbalizing it in class, among peers, helps others connect with the natural and necessary processes of not knowing. They may miss it now, but will grasp it later in a different context. My job is to help them connect not knowing with their intuition or later knowing. The whole course is founded on the spaces between understanding and applying. It is a verbal articulation about what is often nonverbal. Play can get the student to the next nonverbal question of “how do I make this mine?”

In Benjamin Bloom’s pyramid structure, there is a progressive rise expected, learning at its base the skills of Remembering and Understanding, growing more complex when Applying and Analyzing, and moving towards Evaluating and Creating. How I use this language is to condense or assume that with every learning component, students move from Understanding (assuming Remembering) to Applying (assuming Analyzing) into the areas of “Integrating” that include Evaluating, Synthesizing, and Creating. The latter refers to creating by employing the course concepts and practices to and through one’s own sensibilities. The use of "Integrating" is influenced by L. Dee Fink’s "Significant Learning Experiences," which was explored in the Pratt CTL Learning Community called the Broccoli Group, where the visuals were adapted. Integrating, like the terms Understanding and Applying, has a very hands-on nature and feels practical enough for students as they work and reflect on their process. The vocabulary reflects where students are with their learning process—“Understanding, Applying, Integrating” is a fairly quick review of how the student is doing while in the moment-by-moment workshop environment. In the Bloom structural model, we see learning that suggests a single direction—upwards. The single words are direct, useful, and practical for studio learning, but the progressive and ascending nature of the process is less pyramidical and more like monkey bars, with each learner needing to move in their own learning natures. Bloom’s levels of learning are great for self-reflection in conversation and feedback about growth and learning, but not for assessment in learning. What gets to a deeper and more panoramic self-reflection process is the daily use of a Process Book Record of collecting and reviewing working processes and products over time. It holds the potential for students and the teacher to watch or catch moments of developments and changes in learning.

![]()

Figure 2

Fink’s Diagram, Brooks Adaptation

![]()

Self-Reflection and Watching Growth

Weekly Shared & Individual Google-Slide Process Books and "Check-In" Processes

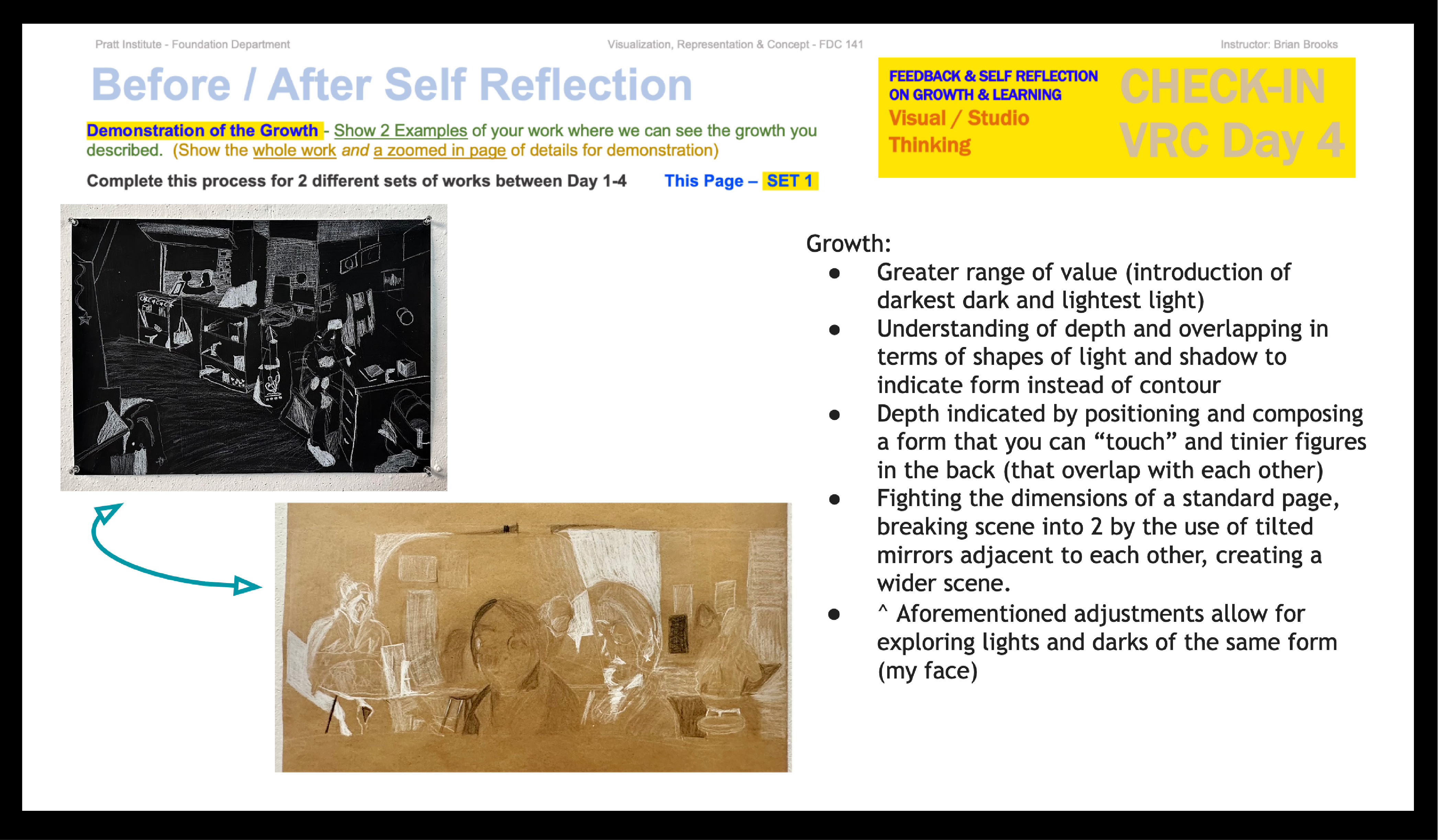

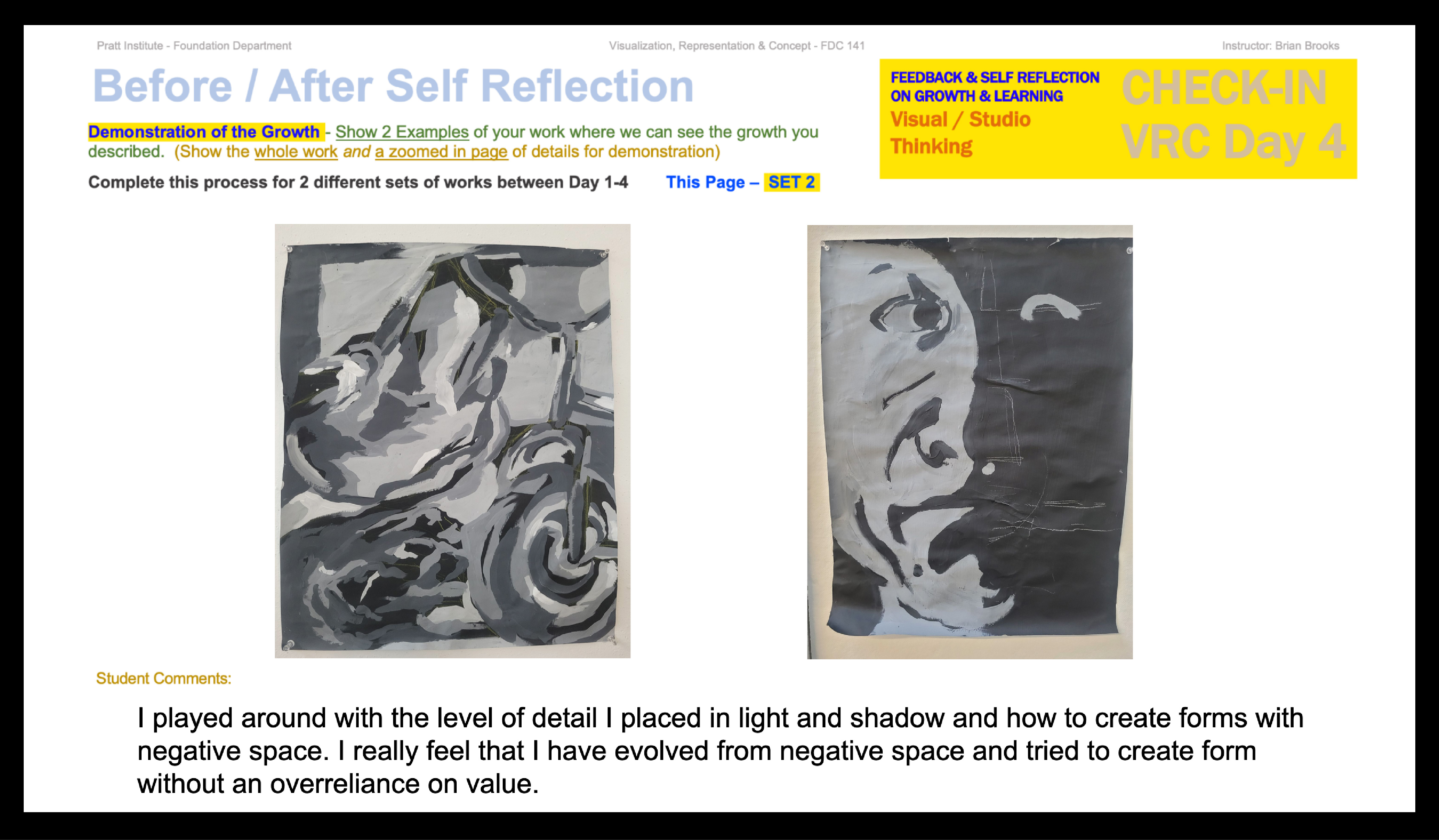

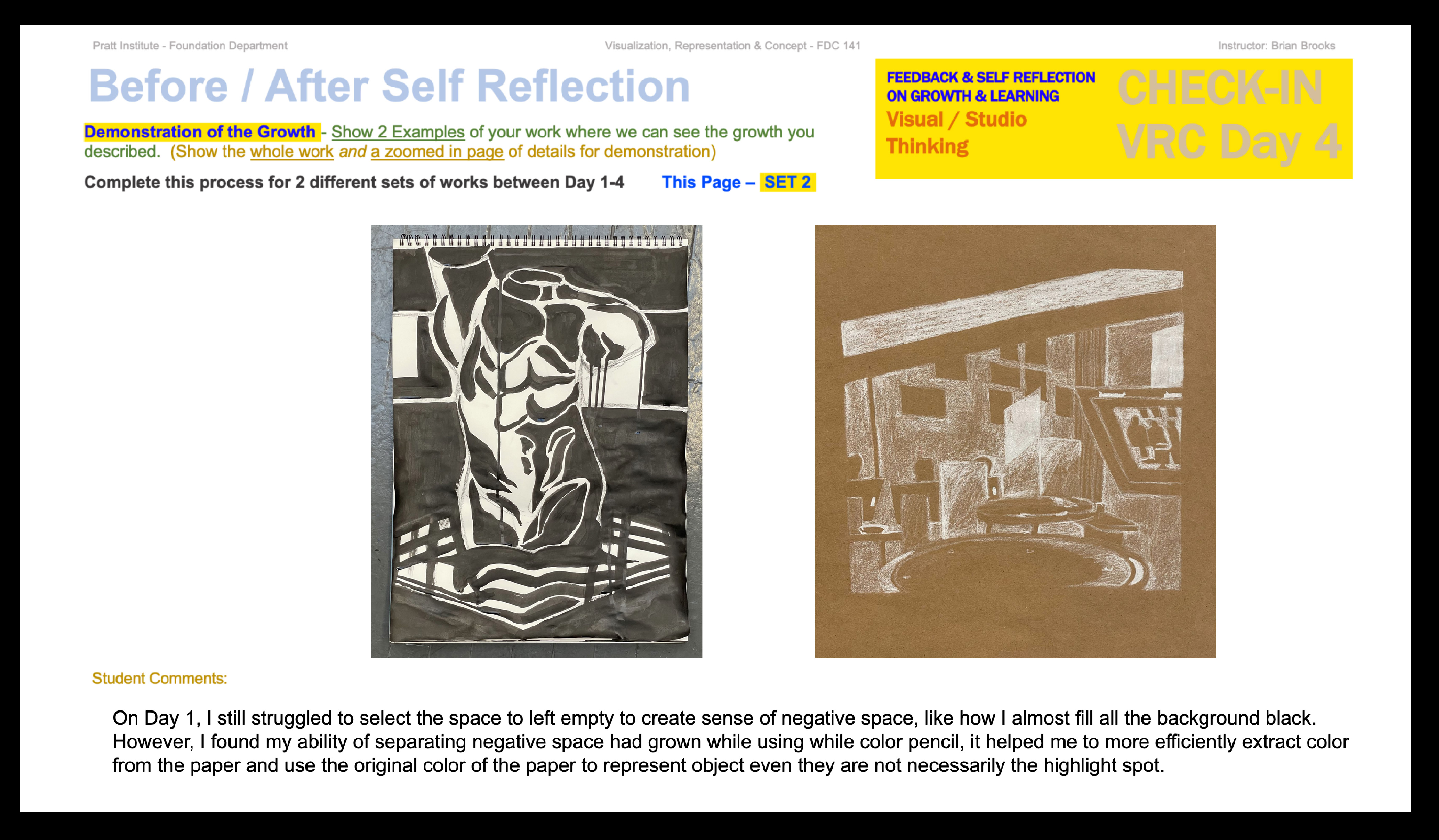

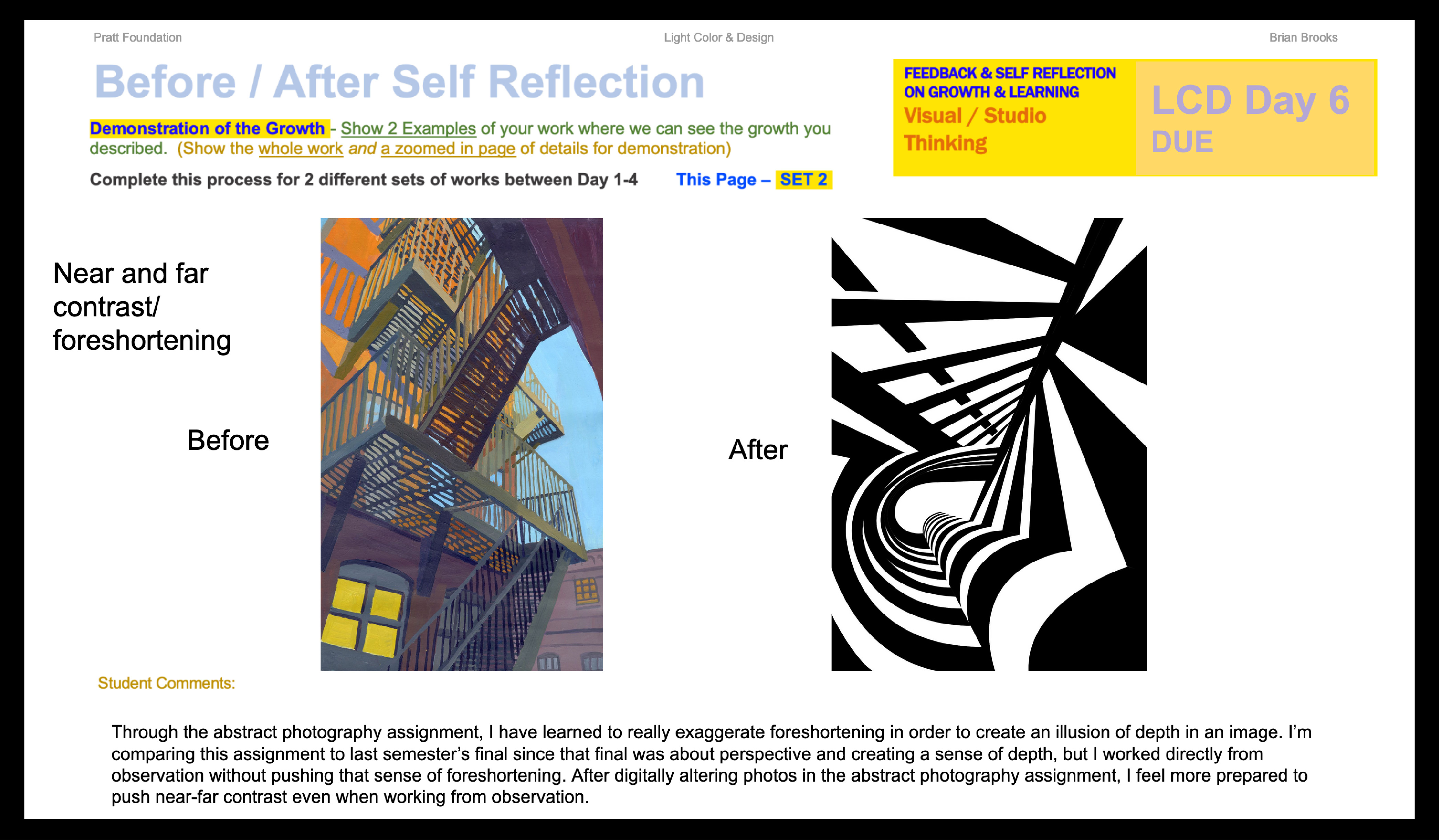

Rather than using the process of a middle of the semester review, known as a "Mid-Term" review, I have found using a quick "Check-In" conversation three times in the semester to be more useful for students to consider a shorter review of material. For those having particular difficulties, it helps them and me problem-solve their learning challenges. In the past, I have used several approaches to these check-ins. For the first check-in, I have used a one-page "3 Circle Identifier,'' or an even simpler "Plus & Question" method. For the second check-in, students make a "Before & After" comparison of works that, in their minds, reflect where and how they have grown using a course concept or practice. Each of these shown here are self-explanatory and make use of a linear weekly visual Process Book (PB) as a repository of student work. Students copy/paste their pages from the Shared PBs into their own individual Process Books. While the Shared PBs are helpful when showing digital work––steps and stages of working––they also help students step back from the actual work to see a record of the work collectively. It is in the Individual PB where students place these check-ins and meet with me to chat about: 1) their growth or need for improvement, and 2) their own comparisons and commentaries concerning the evidence they see and show about their growth. The Before & After Check-In is a conversation starter, but in their own semester-long Individual PB we can go back and forth in time together, watching moments where they can see and grasp their arrivals at levels of Integration, Applying, and Understanding. As a more objective viewer, I can help students see what is harder to see on their own. It is common that students have a challenge seeing their steps fairly, because they expect change to be big, and when it is not so, they tend to miss its significance. I provide a more generous spirit looking for growth, primarily because I know that practicing conceptual tasks does result in increased fluency. I watch for it and magnify its importance continuously!

In numerous instances, Winstone & Boud, in their article, "The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education," present how summative assessment and grading are at odds with students benefiting from, and internalizing, feedback. In Henderson, et al. (2019), the authors define feedback as “processes where the learner makes sense of performance-relevant information to promote their learning” (p. 268). When students discuss letter grades, these authors find that students focus less on the feedback, which is the point of learning and is student centered as it is connected only with that student (Winstone & Boud, 2022).

Winstone & Boud (2022) have this to say about such reflective instruments as process books:

This is critical for how a classroom experience can funnel outwards to the wider world where course learning may integrate more fully, apply to new and unforeseen uses, and transfer to processes based on the learner's own paths and directions beyond school.

As suggested in this quote above, relating to confidence and self-concept and in Fink's circular visualization of learning under "Integration," where he sees the potential for connecting between "ideas, people and realms of life," (Fink, 2003, p.50), the Feedback process has greater correspondence between the problem-solving in course learning and the greater world beyond schools and institutions. The last memories of students in their learning environments should not be what grade they received. Their final impression of the course should be a guided self-reflection on their participation in learning, doing, making, trying, failing, trying again. It is essential for students to form an education journey so that they can feel accomplished within themselves and not from outside systems of validation, validation that explains nothing about them or their processes.

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Henderson, M., Molloy, E., Ajjawi, R., & Boud, D. (2019). Designing feedback for impact. In M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy (Eds.), The impact of feedback in higher education (pp. 267–285). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_1

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2022).

The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 656–667.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687

Engaging in a shared “Gradeless” cohort offered me a chance to focus only on offering students feedback for learning. This dropped the burden of using grades. I do not use crits, a formal group sit-down reviewing everyone’s work methodically, but have elicited conversations about “noticing,” observing things about the work and asking where someone really innovated with the given assignment. Distinctions between subjective and objective observations are encouraged (if they can be identified by the student). Focusing on where and how course concepts are being used excitingly and where improvements can be made is the key goal for these pin-ups.

Collective conversations are gathering points in class sessions, but feedback conversations are happening throughout the workshop nature of the studio class time. I take open-air walks around the room, continuously observing, coaching, noticing aloud, making references to the collective conversations, helping students one on one publicly and in collaboration with peers. This makes use of many layers of the feedback process. A part of this process is reminding students to photograph their process frequently. Students are regularly asked to come over and see what this or that person has just done. (I purposefully do this with students whose work does not get attention, because in the public nature of the workshop, we are really learning from the diversity of sensibilities in the group.) Through this process, there is no way for students to think I am not giving them regular feedback all the time. It is part of the air of the studio classroom.

Studio makers have a hard time reflecting on their moment-by-moment achievements or where they have strayed from the goals of the assignment, because studio making is a complex, simultaneous, whirling storm of different kinds of activities. We easily become distracted, sidetracked, and sometimes these distractions lead to important discoveries. Sometimes these distractions represent a tendency to avoid hard things to do. That avoidance might translate to comfort, as those behaviors are tendencies learned before coming to college. There is nothing wrong with this. Learning is a challenge, as often it is a space of critical thinking and problem solving within an organized and outcome-based college course.

When students work on homework, they often are not pulled from their moment-by-moment worlds to stop, step back, rotate the work upside down, see it from across the room, look at someone else trying to do the same thing but in a totally different way that can baffle the student or offer infectious influence.

The workshop that includes moment-by-moment feedback models a way to work. Focus, move ahead, and then stop, step back, and reflect.

How can grading capture the dynamics of a feedback-centered workshop? Seemingly, the only possible way is to witness and reflect on the engagement and growth of the student, with consideration for how they internalize the course material and individually put it into motion. A grading system like A, B, C is grossly inefficient. Unless everyone gets an A for engagement, grading is outside of the air and atmosphere in the studio workshop.

A Language of Self-Reflection for the Workshop Learning Process

The required Foundation courses I teach have very large parts of them that will be completely new for first-year art and design college students. Many students begin Foundation at Pratt as fifth-year high school students. The shift in learning is often enormous. Many high school art or design courses are product driven where results of projects are pre-known and pre-exist. Students want me to show them an example of how the final work should look. If I taught a course based on this model, it would make sense to have an A–C grade system. But when teaching a visual-concept- and practice-based course where learning happens by doing individually within the shared collective community of the course, differences in learning re-create the learning material. No semester results in the same achievements because the learner changes the course.

Students in this environment go through the challenging process of learning a visual design principle by experimenting with its components and building upon earlier scaffolding learning components. They are asked to make use of new and previous things learned in new learning problems.

Students in this process commonly say, “I understand it but have a hard time applying it.” Because the air in the studio is filled with feedback, the door opens to a particular use of “Bloom’s Taxonomy” (Armstrong, 2010), making his “learning level vocabulary” concrete and practical and of the moment. The student making this statement (someone every year does so…) indicates that they have a minor crisis in learning. Understanding is one thing, but applying it is another. The student can seem stuck, unable to play, but most often seems to be reporting a gap in rationality and intuition or stating that something is out of reach. This is a minor event, but verbalizing it in class, among peers, helps others connect with the natural and necessary processes of not knowing. They may miss it now, but will grasp it later in a different context. My job is to help them connect not knowing with their intuition or later knowing. The whole course is founded on the spaces between understanding and applying. It is a verbal articulation about what is often nonverbal. Play can get the student to the next nonverbal question of “how do I make this mine?”

In Benjamin Bloom’s pyramid structure, there is a progressive rise expected, learning at its base the skills of Remembering and Understanding, growing more complex when Applying and Analyzing, and moving towards Evaluating and Creating. How I use this language is to condense or assume that with every learning component, students move from Understanding (assuming Remembering) to Applying (assuming Analyzing) into the areas of “Integrating” that include Evaluating, Synthesizing, and Creating. The latter refers to creating by employing the course concepts and practices to and through one’s own sensibilities. The use of "Integrating" is influenced by L. Dee Fink’s "Significant Learning Experiences," which was explored in the Pratt CTL Learning Community called the Broccoli Group, where the visuals were adapted. Integrating, like the terms Understanding and Applying, has a very hands-on nature and feels practical enough for students as they work and reflect on their process. The vocabulary reflects where students are with their learning process—“Understanding, Applying, Integrating” is a fairly quick review of how the student is doing while in the moment-by-moment workshop environment. In the Bloom structural model, we see learning that suggests a single direction—upwards. The single words are direct, useful, and practical for studio learning, but the progressive and ascending nature of the process is less pyramidical and more like monkey bars, with each learner needing to move in their own learning natures. Bloom’s levels of learning are great for self-reflection in conversation and feedback about growth and learning, but not for assessment in learning. What gets to a deeper and more panoramic self-reflection process is the daily use of a Process Book Record of collecting and reviewing working processes and products over time. It holds the potential for students and the teacher to watch or catch moments of developments and changes in learning.

Figure 1

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Figure 2

Fink’s Diagram, Brooks Adaptation

Self-Reflection and Watching Growth

Weekly Shared & Individual Google-Slide Process Books and "Check-In" Processes

Rather than using the process of a middle of the semester review, known as a "Mid-Term" review, I have found using a quick "Check-In" conversation three times in the semester to be more useful for students to consider a shorter review of material. For those having particular difficulties, it helps them and me problem-solve their learning challenges. In the past, I have used several approaches to these check-ins. For the first check-in, I have used a one-page "3 Circle Identifier,'' or an even simpler "Plus & Question" method. For the second check-in, students make a "Before & After" comparison of works that, in their minds, reflect where and how they have grown using a course concept or practice. Each of these shown here are self-explanatory and make use of a linear weekly visual Process Book (PB) as a repository of student work. Students copy/paste their pages from the Shared PBs into their own individual Process Books. While the Shared PBs are helpful when showing digital work––steps and stages of working––they also help students step back from the actual work to see a record of the work collectively. It is in the Individual PB where students place these check-ins and meet with me to chat about: 1) their growth or need for improvement, and 2) their own comparisons and commentaries concerning the evidence they see and show about their growth. The Before & After Check-In is a conversation starter, but in their own semester-long Individual PB we can go back and forth in time together, watching moments where they can see and grasp their arrivals at levels of Integration, Applying, and Understanding. As a more objective viewer, I can help students see what is harder to see on their own. It is common that students have a challenge seeing their steps fairly, because they expect change to be big, and when it is not so, they tend to miss its significance. I provide a more generous spirit looking for growth, primarily because I know that practicing conceptual tasks does result in increased fluency. I watch for it and magnify its importance continuously!

Figure 3

Plus & Question Reflection

![]()

Plus & Question Reflection

Figure 4

Circle Reflections

![]()

Figure 5

Before & After Reflection 1

![]()

Figure 6

Before & After Reflection 2

![]()

Figure 7

Before & After Reflection 3

![]()

Figure 8

Before & After Reflection 5

![]()

Figure 9

Before & After Reflection 6

![]()

Figure 10

Before & After Reflection 7

![]()

Figure 11

Before & After Reflection 8

![]()

Figure 12

Before & After Reflection 9

![]()

Figure 13

Before & After Reflection 10

![]()

Feedback on Growth and Improvement is “Student Centered” / Numbers or Letter Grades are “Institution Centered”Circle Reflections

Figure 5

Before & After Reflection 1

Figure 6

Before & After Reflection 2

Figure 7

Before & After Reflection 3

Figure 8

Before & After Reflection 5

Figure 9

Before & After Reflection 6

Figure 10

Before & After Reflection 7

Figure 11

Before & After Reflection 8

Figure 12

Before & After Reflection 9

Figure 13

Before & After Reflection 10

In numerous instances, Winstone & Boud, in their article, "The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education," present how summative assessment and grading are at odds with students benefiting from, and internalizing, feedback. In Henderson, et al. (2019), the authors define feedback as “processes where the learner makes sense of performance-relevant information to promote their learning” (p. 268). When students discuss letter grades, these authors find that students focus less on the feedback, which is the point of learning and is student centered as it is connected only with that student (Winstone & Boud, 2022).

Winstone & Boud (2022) have this to say about such reflective instruments as process books:

Ongoing curation of feedback is also important to position the purpose of feedback as more than just improvement in numerical performance. Tracking the impact of feedback could enable students to recognize the influence of feedback processes on key outcomes such as confidence, skills, self-concept, and employability. (p. 665)

This is critical for how a classroom experience can funnel outwards to the wider world where course learning may integrate more fully, apply to new and unforeseen uses, and transfer to processes based on the learner's own paths and directions beyond school.

As suggested in this quote above, relating to confidence and self-concept and in Fink's circular visualization of learning under "Integration," where he sees the potential for connecting between "ideas, people and realms of life," (Fink, 2003, p.50), the Feedback process has greater correspondence between the problem-solving in course learning and the greater world beyond schools and institutions. The last memories of students in their learning environments should not be what grade they received. Their final impression of the course should be a guided self-reflection on their participation in learning, doing, making, trying, failing, trying again. It is essential for students to form an education journey so that they can feel accomplished within themselves and not from outside systems of validation, validation that explains nothing about them or their processes.

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Henderson, M., Molloy, E., Ajjawi, R., & Boud, D. (2019). Designing feedback for impact. In M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy (Eds.), The impact of feedback in higher education (pp. 267–285). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_1

Winstone, N. E., & Boud, D. (2022).

The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 656–667.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687

Introduction

A note on timing: The specific technologies in the public eye at the time of publication will likely differ from those discussed here, but I expect that the central concept—how we communicate about technologies that are rapidly changing—will continue to be relevant.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been recently spotlighted as a point of innovation and concern for many educators and institutions of higher education. Though generative AI is not the only type of artificial intelligence applied within educational spaces, the accelerated growth of these tools demands our attention. These systems will continue growing in popularity and influence, and because of the immediate impacts on the experiences of teaching and learning, educators are entangled in this process. As these tools proliferate—and the sizes and capabilities of the models grow at an exponential rate—conversations about AI are increasingly necessary.

How do we (as educators, learners, scholars, and humans) promote dialogue around tools that are rapidly changing?

A note on timing: The specific technologies in the public eye at the time of publication will likely differ from those discussed here, but I expect that the central concept—how we communicate about technologies that are rapidly changing—will continue to be relevant.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been recently spotlighted as a point of innovation and concern for many educators and institutions of higher education. Though generative AI is not the only type of artificial intelligence applied within educational spaces, the accelerated growth of these tools demands our attention. These systems will continue growing in popularity and influence, and because of the immediate impacts on the experiences of teaching and learning, educators are entangled in this process. As these tools proliferate—and the sizes and capabilities of the models grow at an exponential rate—conversations about AI are increasingly necessary.

How do we (as educators, learners, scholars, and humans) promote dialogue around tools that are rapidly changing?

GenAI and Creative Practices

With innovations in GenAI systems, the uses of artificial intelligence for end-users with no programming experience have moved from predictive text, grammar correction software, and recommendation systems to the generation of entirely unique text, images, audio, and even video. Recent GenAI developments offer new tools and opportunities for creative practitioners, supporting individual artists, teams, and organizations in realizing their creative visions beyond what was previously assumed to be possible. This potential is being recognized globally, and AI is increasingly being integrated into pipelines for design studios and various creative industries (Chatzitofis et al., 2023; Ladicky & Jeong, 2023; Suessmuth et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Educators within the context of arts, design, and architecture institutions are caught in the crossfire of multiple motivators and considerations:

With innovations in GenAI systems, the uses of artificial intelligence for end-users with no programming experience have moved from predictive text, grammar correction software, and recommendation systems to the generation of entirely unique text, images, audio, and even video. Recent GenAI developments offer new tools and opportunities for creative practitioners, supporting individual artists, teams, and organizations in realizing their creative visions beyond what was previously assumed to be possible. This potential is being recognized globally, and AI is increasingly being integrated into pipelines for design studios and various creative industries (Chatzitofis et al., 2023; Ladicky & Jeong, 2023; Suessmuth et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Educators within the context of arts, design, and architecture institutions are caught in the crossfire of multiple motivators and considerations:

Artists and designers are often among the first to test new technologies, push them to their limits, and explore the social and artistic ramifications of these tools. As creative practitioners constantly explore their contexts through various mediums, art and design students are poised to create entirely new artistic methodologies with access to such powerful generative systems. AI tools integrated into the creative processes of talented artists and designers have the potential to shorten the amount of time that any one person spends on labor intensive tasks, while also opening access to creative forms that have typically been exclusive to those with expert-level programming skills. (Cremer et al., 2023)

However, the ability to generate novel text, images, audio, and video—all of which are imbued with their own aesthetics, datasets, contexts, constitutions, and biases—disrupts traditional notions of originality and authorship in the classroom. How do we, as art and design educators, balance our excitement for new tools and creative methods with valid and immediate concerns about shifting expectations around authorship and originality, as well as the value of study, research, and creative struggle for learners?

Immediate Action

The real, felt impacts of generative AI on the classroom space necessitate some form of response to the immediate challenges. Finding solutions for shortcomings within a technological system may be necessary to support the critical needs of a community. For example, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, instructors needed to respond quickly and with agility to provide accessible online materials for newly remote students. Instructors across the country and the globe were thrown into Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT): a necessary response to vicissitudes in the learning environment, “a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate mode due to crisis circumstances” (Hodges et al., 2020, as cited in Erlam et al., 2021, p. 2). While ERT was essential in getting learning materials online quickly, it differs greatly from effective and quality online teaching (Hodges et al., 2020). This experience can provide a perspective on responding to other forms of change within learning environments, including the rapid progression of GenAI.

The Rate of Growth

While immediate action through policies, assignment revisions, and shifting classroom dynamics may be necessary as a quick response to changing circumstances, it is not a substitute for lasting systemic change. Conversations around artificial intelligence systems and other emergent technologies should not only depend on the current state of advancements in order to justify appropriate responses. The number and quality of tasks completed with the use of GenAI systems is accelerating at a fast pace, and evaluating these systems in relation to their current deficits and faults can lead to continually reevaluated strategies. 1

1As an example, in the early days and weeks after the release of ChatGPT, a suggestion for instructors assigning written assessments was to incorporate questions that refer to materials produced after the end date of the model’s training data (at the time, GPT-3 was trained on a set of information which concluded in September 2021); as of October 2023, OpenAI has re-released Browsing for Pro and Enterprise users of Chat, allowing for access to the open web.

When considering potential strategies for discussing rapidly changing technologies, pedagogical lenses from tech-related disciplines provide valuable and applicable perspectives. Drawing upon studies from the fields of computer graphics and animation, there is evidence that by learning high level theoretical concepts alongside introductory technical concepts, students are poised to adapt their learning skills to new applications as technology continues to change. This counteracts the “trap of only teaching lower level learning to ‘keep-up’ with new technology advancements in upper level courses,” and instead allows for a greater degree of flexibility in a changing technological landscape (Whittington & Nankivell, 2006).

These principles are applicable not just in formal lessons, but also in more informal dialogue around emerging technology. Integrating this framework of agility into our discussions about artificial intelligence and avoiding reactive decision- and policy-making can help us to avoid constantly re-evaluating our standards. Reflecting this into the classroom, the value of adaptable learning—within the context of technology or otherwise—cannot be easily overstated; to imbue learners with sustainable conceptual skills that can adapt to changing circumstances is a worthwhile goal.

Sense-Making in Synthetic Realities

As developments in GenAI continue to accelerate, the field does not progress in a vacuum. GenAI, brain-computer-interfaces (BCIs), quantum computing, robotics, and innovative uses of haptic feedback are all being transformed simultaneously; alongside other emerging technologies, these innovations contribute to new synthetic realities.2

2Generative AI in particular presents an additional level of mediation between ourselves and formal reality, which offers radically new opportunities for creative exploration while also suggesting an isolation between the self and the surrounding realities (Cole & Grierson, 2023, p. 10).

Synthetic realities are “[virtual environments] which become experienced comprehensively as new versions of reality” and, as technology advances, are treated as real (Wolcott, 2017). These synthetic realities are vastly improved by advancements in AI, and recent definitions of synthetic reality make this linkage explicit: they are the realities AI enables us to create (White, 2023).

Rather than asking whether or not these realities are real, the Center for Humane Technology suggests we ask whether people will change things about their lives for these new realities (2023). The answer is already yes—people have lost employment, given away large sums of money, and altered the outcomes of political elections due to their willingness to change aspects of their lives based on synthetic realities (Brodkin, 2022; Conradi, 2023; Evans & Novak, 2023; “When Love Is a Lie,” 2023). In more subtle ways, even simple text-based GenAI products have the potential to influence the user’s understanding of the prompt subjects.

In “The Normative Power of Artificial Intelligence,” Giovanni De Gregorio (2023) writes:

Algorithmic technologies are not only instruments to exercise powers, which can interfere with fundamental rights, but can also be considered as rule-makers. Rather than mere executing tools based on pre-settled instructions and standards, machine learning, and deep learning, systems learn how to perform their task and adapt it through experience. In this case, these systems exercise normative powers. (p. 3)

Norms produced through the laws of nature are predictable, to some extent, and can be understood, such as by gravity; in the field of AI, norms are created without the potential of entirely predicting or understanding the forces which create said norms (De Gregorio, 2023, p. 11). Evidence has begun to suggest that large language models have the potential, and perhaps even trend toward, developing practices which obscure levels of encoded reasoning from human readers (Roger & Greenblatt, 2023). In Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, Hito Steyerl (2017) remarks upon the prevalence of unpredictable and unidentifiable forces:

Not seeing anything intelligible is the new normal. Information is passed on as a set of signals that cannot be picked up by human senses. Contemporary perception is mechanic to a large degree. The spectrum of human vision only covers a tiny part of it. Electric charges, radio waves, light pulses encoded by machines for machines are zipping by at slightly subluminal speed. Seeing is superseded by calculating probabilities. Vision loses importance and is replaced by filtering, decrypting, and pattern recognition. (p. 5)

New skills are needed, new methods of sense-making. Because of the pervasive nature of these technologies, the development of these new skills and methods cannot be left only to instructors in the fields of computer science and programming. While technical knowledge—becoming proficient at utilizing specific tools and processes and understanding when each of these tools and/or processes should be applied—is absolutely essential in any discipline, the nature of artificial intelligence necessitates a new framework that includes responsible tech and information literacy practices at every level of study. In “Authentic Integration of Ethics and AI Through Sociotechnical, Problem-Based Learning,” a study on integrating problem-based learning and responsible technoethics into pedagogical approaches, Krakowski et al. (2022) asserts that “an approach that integrates AI technical and ethical domains should not be limited to those already advanced along academic and career pathways to AI,” and should instead be accessible to anyone who is incorporating artificial intelligence into their workflows in or out of the classroom (p. 12780).

At this pivotal moment, artificial intelligence systems are advancing exponentially, as is the number of people learning to integrate these technologies within their personal and professional work. It is then “critical that all learners—whether or not they aspire to pursue academic or workforce pathways in AI—develop a foundational understanding not only of how AI systems operate, but also of the principles that can guide the responsible development, implementation, and monitoring of those systems” (Krakowski et al., 2022, p. 12779).

Everyday AI has proliferated in our lives, and now the intentional adoption of AI tools is becoming widespread; how can we collectively work to ensure that there is a synchronous growth of knowledge about responsible technology frameworks? It is vital that we name this need and that we enact it within educational spaces, especially as “Techno-Optimists” publicly decry “trust and safety,” “tech ethics,” and “risk management” as “The Enemy” (Andreessen, 2023). In “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Cultural and Creative Sectors,” an introductory briefing written for the European Parliament by Baptiste Caramiaux in 2020, Caramiaux outlines the importance of cultural and academic institutions to sustain public conversations around the uses and applications of AI; he describes a potential relationship between the public, cultural sectors, and arts innovators that can move the field of artificial intelligence forward with accessibility and cultural competency at the forefront.

TL;DR

How do we hold dialogue around tools that are rapidly changing? By striving to create lasting systemic change rather than focusing on temporary solutions, teaching ethical and responsible technology frameworks alongside technical lessons, and actively developing agile skills that support us through change. Multi-faceted dialogue around emerging technologies can support the responsible implementations of new tools, teach agility, and develop new means of sense-making.

At this pivotal moment, artificial intelligence systems are advancing exponentially, as is the number of people learning to integrate these technologies within their personal and professional work. It is then “critical that all learners—whether or not they aspire to pursue academic or workforce pathways in AI—develop a foundational understanding not only of how AI systems operate, but also of the principles that can guide the responsible development, implementation, and monitoring of those systems” (Krakowski et al., 2022, p. 12779).

Everyday AI has proliferated in our lives, and now the intentional adoption of AI tools is becoming widespread; how can we collectively work to ensure that there is a synchronous growth of knowledge about responsible technology frameworks? It is vital that we name this need and that we enact it within educational spaces, especially as “Techno-Optimists” publicly decry “trust and safety,” “tech ethics,” and “risk management” as “The Enemy” (Andreessen, 2023). In “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Cultural and Creative Sectors,” an introductory briefing written for the European Parliament by Baptiste Caramiaux in 2020, Caramiaux outlines the importance of cultural and academic institutions to sustain public conversations around the uses and applications of AI; he describes a potential relationship between the public, cultural sectors, and arts innovators that can move the field of artificial intelligence forward with accessibility and cultural competency at the forefront.

TL;DR

How do we hold dialogue around tools that are rapidly changing? By striving to create lasting systemic change rather than focusing on temporary solutions, teaching ethical and responsible technology frameworks alongside technical lessons, and actively developing agile skills that support us through change. Multi-faceted dialogue around emerging technologies can support the responsible implementations of new tools, teach agility, and develop new means of sense-making.

Resources and Recommendations

- Interdisciplinary, Pratt-specific conversations about AI are hosted frequently by Holly Adams through the Center for Teaching and Learning

- The Teaching AI Ethics series by Leon Furze provides case studies, discussion questions, and resources for including AI ethics lessons in classes

- Center for Humane Technology has a free, self-paced online course, Foundations of Humane Technology, geared towards technologists but beneficial to anyone interested in learning more about the ways in which persuasive technologies have impacted our lives and strategies to move forward as a collective

- Practical Data Ethics by fast.ai, another free online course, provides context about data misuse, including topics such as algorithmic colonialism, our ecosystem, and privacy and security

- Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence is developing research centering the enhancement of human intelligence, and the respect of human vulnerabilities, with AI

- The Algorithmic Justice League works to raise awareness about the impacts of artificial intelligence, advocating for responsible and equitable AI ecosystems

References

Andreessen, M. (2023, October 16). The techno-optimist manifesto. Andreessen Horowitz. https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/

Brodkin, J. (2022, July 25). Google fires Blake Lemoine, the engineer who claimed AI chatbot is a person. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2022/07/google-fires-engineer-who-claimed-lamda-chatbot-is-a-sentient-person/

Caramiaux, B. (2020). Research for CULT Committee—The use of artificial intelligence in the cultural and creative Sectors. European Parliament Think Tank. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_BRI(2020)629220

Center for Humane Technology. (2023). Synthetic humanity: AI & what’s at stake (63). https://www.humanetech.com/podcast/synthetic-humanity-ai-whats-at-stake

Chatzitofis, A., Albanis, G., Zioulis, N., & Thermos, S. (2023). Suit up: AI MoCap. ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Real-Time Live!, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3588430.3597249

Cole, A., & Grierson, M. (2023). Kiss/crash: Using diffusion models to explore real desire in the shadow of artificial representations. Proceedings of the ACM on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, 6(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/3597625

Conradi, P. (2023, October 7). Was Slovakia election the first swung by deepfakes? The Sunday Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/was-slovakia-election-the-first-swung-by-deepfakes-7t8dbfl9b

Cremer, D. D., Bianzino, N. M., & Falk, B. (2023, April 13). How generative AI could disrupt creative Work. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/04/how-generative-ai-could-disrupt-creative-work

De Gregorio, G. (2023). The normative power of artificial intelligence (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4436287). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4436287

Erlam, G. D., Garrett, N., Gasteiger, N., Lau, K., Hoare, K., Agarwal, S., & Haxell, A. (2021). What really matters: Experiences of emergency remote teaching in university teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.639842

Evans, C., & Novak, A. (2023, July 19). Scammers use AI to mimic voices of loved ones in distress. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/scammers-ai-mimic-voices-loved-ones-in-distress/